Review by Sharon Tracey

Review by Sharon Tracey

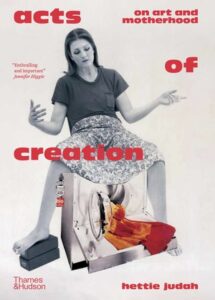

In Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood, art critic and curator Hettie Judah takes the reader on a wide-ranging and engaging “imaginary museum” tour that examines the many permutations of art lived in and through motherhood. It’s an eye-opening tour de force that challenges readers to consider what hangs in museums and what vanishes in the act of being born.

Early on, Judah sets up themes that she will return to: mothers divine, artist as mother, mother as creator, caregiver, consoler, feminist. With a keen curatorial eye, she has assembled an eclectic and expansive collection, from conceptions of the divine as goddess, saint, icon, nymph, and monster carved in bone and stone, to acts of motherhood reflected in paintings, drawings, prints, photography, and multimedia.

The artworks themselves make a compelling parallel story to the text, amplifying its heft and texture. We see artist-mothers responding to pregnancy, childbirth, raising children, freedom, loss. We see work that is public, personal, spiritual, political. Art that subverts traditional roles, that explores the limits of maternal protection. Art that contemplates the meaning of mothering and the boundaries of family. Judah provides insightful commentary along the way and her “imaginary museum” teems with illustrative examples.

It’s a fresh approach to untangling some common misconceptions in the long history of art when it comes to mothers and motherhood while offering new ways of looking. It’s also satisfying as women artists take up more of the museum space as we move towards the present day.

Judah begins by introducing Marlene Dumas’s striking work, The Painter, 1994, (p 8) which depicts the artist’s five-year old daughter, naked and defiant, hands dipped in red and blue paint. What Judah is particularly interested in and wants to draw attention to: “the conditions of making art as a mother, of having another being standing between you and your work” (p 9). It’s a compelling start and framework for approaching the art to come.

Judah also brings artworks together in effective ways, such as placing Masolino’s Madonna of Humility, c. 1415 next to Winold Reiss’s The Brown Madonna, 1925 next to Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, 1936 (p 20, 21); and in another instance, pairing Seated Woman of Çatalhöyük, 6,000 BCE with Judy Chicago’s Birth, 1984. (p 30, 31). The art, presented in this way, illuminates and invites comparisons in the light of history. All told, 150 artworks are featured, and the representation is wide-ranging, from Berthe Morisot to Jenny Saville, Alice Neel to Kiki Smith, Paula Rego to Carrie Mae Weems, Ana Mendieta to Barbara Walker, among a host of other artists.

What Judah chooses to “hang” in the “imaginary museum” often steers clear of the usual suspects. Instead of one of Suzanne Valadon’s better known reclining nudes, she presents Family Portrait, 1912 (p 101) in which the artist paints herself alongside her mother (who singularly raised her and her sister), her son (whom her mother helped raise so she could paint), and her lover (who championed her art after she left her husband). Not the traditional family portrait one might expect in the early years of the 20th century. As Judah notes, [the]“painting acknowledges the circumstances of its production.” (p 104) and this consideration—looking at the circumstances of production—threads its way throughout the book, offering new ways to consider and appreciate the art.

Some of the art is provocative and all of it is thought-provoking. The reader/viewer will connect with some of the art more than other works, just as one would in any art museum. But through the wide scope and sweep of Judah’s deep analysis and commentary, readers will come away with a broader understanding and appreciation for the challenges and accomplishments of the mother-artist as cultural icon, as well as being introduced to new artists and work. Motherhood in art and its history is entwined with love, family, power, struggle, freedom, grief and loss and Judah does a terrific job of expanding our understanding of these interconnections. Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood is a thrilling ride and breaks new ground by connecting motherhood and art in revealing ways while opening a door to more expansive views of mothering.

Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood by Hettie Judah

Thames & Hudson, 2024 $39.95 (hardback)

ISBN: 9780500027868

Sharon Tracey is a poet and editor and the author of three books of poetry: Land Marks (Shanti Arts 2022), Chroma: Five Centuries of Women Artists (Shanti Arts 2020), and What I Remember Most is Everything (All Caps Publishing). Her work has appeared in Radar Poetry, Terrain.org, Lily Poetry Review, The Ekphrastic Review, and elsewhere. She previously served as a director of research communications and environmental initiatives at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.