Review by Teresa Tumminello Brader

Review by Teresa Tumminello Brader

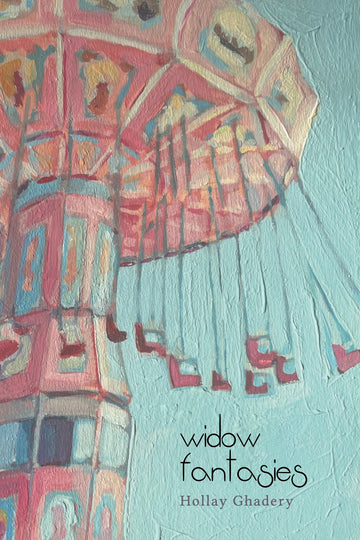

Hollay Ghadery is the author of a memoir, Fuse, recipient of a Canadian Bookclub Award for Nonfiction/Memoir; a collection of poetry, Rebellion Box; and, most recently, a short-fiction collection, Widow Fantasies (Gordon Hill Press, September 2024). In eighty-three pages, and with a gorgeous cover, the latter contains more than thirty stories of female fantasizing as a response and release to the frustration and rage at existing in a world of suppression.

In fewer than three pages, the first story sets the tone, accommodating anger with humor and pathos. The unnamed first-person narrator is a recent empty-nester who has bonded and is obsessed with her eponymously-named goldfish Jaws. “When Reza’s mistress died last year, Jaws was the only one I let see me cry. She understood: it was my loss as much as his. The woman had been oxygen to our little bowl of stagnant water. She’d given me room to breathe.” (2) Attempting to save Jaws in the face of her son’s lack of understanding and her husband’s insensitivity, the woman hopes to save herself.

Despite the book’s title, a few of the protagonists are young girls and men. Through humorous sleights-of-hand, the obliviousness and outer bravado of these men reveal the ways their daughters, granddaughters, and former partners have escaped their control. Perhaps surprisingly, the title story is not of an older woman, but a farm wife with four young children, one a nursing infant. As Leyla cooks breakfast early in the morning, her understated, and understandable, desire to be left alone turns into a nightmare.

The theme of desire—not just sexual desire, though that is a major focus—flows throughout, as in the two-pager “Ditch Run,” in which another wife and mother wants a bit of time on her own, to feel like herself, to fulfill herself. She remembers words of advice given by her father when she was a sixteen-year-old kayaker: “‘The current has the boat, but it doesn’t have you. When in doubt, lean forward, keep paddling.’” (58) His words echo effectively in the open-ended conclusion.

In “Khoshgel” (a Persian word meaning beautiful), a young girl is clueless as to why the female relatives and friends of her pregnant mother are no longer calling her by this term of endearment, one they’d used only minutes before. As in the works of Toni Morrison and Elena Ferrante, the story points toward the eventual deflation of a child’s self-esteem when she realizes that praise (or the lack of such) is due to an outward trait.

Reya smooths her drawing against her chest. She worked on it all morning: a black emperor scorpion. One of the biggest and strongest scorpions in the world but also one of the most docile. The nicest. It’s her favorite arachnid, and since everyone has gathered to give nice things to her mother for her new baby brother, this was her nice thing: A promise to be strong. To be kind. (32)

Reya is blissfully ignorant of her society’s superficial expectations, though the reader senses an upcoming rude awakening. The final story “Tennis Whites” offers a contrast, a young girl with an awareness that gives a cheeky, and fitting, ending to the collection.

Widow Fantasies by Hollay Ghadery

Gordon Hill Press, 2024, 83 pages, $17 [paper]

ISBN 9781774221143

Teresa Tumminello Brader is the author of Letting in Air and Light, a work of hybrid memoir/fiction from Belle Point Press. Her short-story collection Secret Keepers is forthcoming in March 2025 from the same publisher. Her stories, essays, poetry and reviews can be found in print anthologies and at various online literary sites, such as Bulb Culture Collective, Deep South, Halfway Down the Stairs, and MER.