A Literary Reflection by Ellen Meeropol

A Literary Reflection by Ellen Meeropol

I approached reading this novel with the mixed emotions I feel when beginning any novel set in the activism of the 1960s. With fascination, because my world view and personhood was formed in that landscape. And with trepidation, because the author might get it wrong. That period of intense political activism and personal change has been the frequent victim of stereotyping and caricature.

Randy Susan Meyers gets it right.

Art student Annabel and lawyer-to-be Guthrie, fresh from Freedom Summer in Mississippi, answer an ad for Puddingstone, an intentional household in Boston’s Mission Hill looking for a “like-minded couple who believes that justice begins at home.” The commune is looking for people who are “fervent about fighting for freedom and civil right, stopping the war, and loving vegetables.” This is exactly what Annabel and Guthrie want and they move in, enthusiastically joining the chaos and energy, the mess and exuberance.

Scenes of the commune’s discussions – about the politics of housework, about food, about monogamy – are some of the unexpected pleasures of this novel. The author nailed the complicated and often inflammatory mix of friendship and lust, of competing desires for political passion and family stability, of endless political arguments about the relative importance of civil rights and stopping the war vs sexism within the movement. Feminism issues become deeply personal at Puddingstone when Annabel and Guthrie’s children, Ivy and Henry, are born and Annabel drops out of school to care for them.

As political engagement intensifies with escalating violence, the commune buys an old farmhouse in Vermont. Their plan, that the children live on the farm with one full-time mother and a rotating cast of other parents, will remove the children from danger and leave the adults free to work long hours at their activism. There is precedence for sending children away for their safety, from relocating children of the 1912 Lawrence, MA Bread and Roses strikers to USCOM transports of European children to escape the Nazis and sending the children of Africa National Congress activists away from the violence of the struggle. Annabel is torn; the plan will keep her children safe and will leave her free to work long hours at Sojourner Graphics but she doesn’t want them away from her care. Reluctantly, she goes along with the plan. When the children move to Vermont, Annabel and Guthrie’s eleven-year-old daughter Ivy begins to share the narration.

“I lacked the vocabulary or courage,” Ivy reports when her parents call to say they won’t be able to drive up for her birthday, “to say that the only treat I needed was her. I wanted to be as crucial to my mother as Sojourner Graphics and amnesty, the meaning of which was beyond my understanding.” (197.)

No big surprise that things don’t work out well for the Puddingstone children.

Rarely has a novel touched me so deeply. This is partly because Meyers moves the story with urgency and grace between Freedom Summer and 9/11 and beyond, reminding the reader of the complicated political stew of race, class, and gender that has simmered in the past half-century.

Balancing motherhood and work is a challenge for many of us. When our work is activism, the contradictions may run deeper, since activism contributes to the common good rather than the household budget. This balance, between parenting and activism, has haunted my family life. I am aware of how my activism changed in the years my daughters were young. My husband and I took fewer risks, scaling back on actions that could land us in jail, or worse.

Our situation was unusual. My husband’s parents, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, were Communists targeted for their activism against the rise of fascism in the years leading up to the Holocaust. When my husband and his brother were born, Ethel dropped out of most political work to stay home with her sons while Julius continued aiding the Soviet Union’s efforts to defeat Hitler. I often wonder what Ethel thought about those decisions. Ethel and Julius were executed for their politics, orphaning their boys. In our family, the risks felt personal.

I thought about my in-laws as I read about the great lengths Puddingstone adults went to, trying to keep their children safe and well cared for while working for radical change.

Today, many parents are resisting another wave of advancing fascism. As we work to create families and communities built on progressive values, we need stories like The Many Mothers of Ivy Puddingstone that interweave political activism with domesticity, stories that illuminate the challenges and joys of growing a just future for the children of the world.

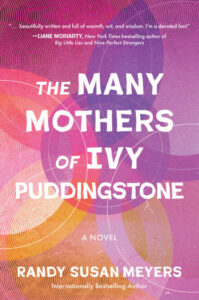

The Many Mothers of Ivy Puddingstone by Randy Susan Meyers.

Koehler Books, October 29, 2024.

979-8-88824-533-0

Ellen Meeropol is the author of five novels including The Lost Women of Azalea Court and Her Sister’s Tattoo, and guest editor of the anthology Dreams for a Broken World. Essay and short story publications include Ms. Magazine, Lilith, The Writer Magazine, Literary Hub, Guernica, and The Boston Globe.