I was not given meaning, so I had to make it

I was not given meaning, so I had to make it

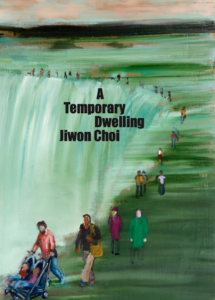

By Jiwon Choi

I can’t say that I was feeling overtly political during the drafting of A Temporary Dwelling, my third poetry collection (Spuyten Duyvil, 2024), but I do acknowledge that I am distrustful of the Mainstream Culture seeing how it tries to jam unhelpful messages through my keyhole. A slightly contradictory statement coming from someone whose childhood was taken up with voraciously imbibing what the MC had to offer, primarily in TV form whilst waiting for the parents to get home. Yes, I was a child in the clutches of popular culture’s long arms and sharp talons. Still a wee bit in awe of it.

We landed in New York City from Korea in 1972, with three more war years to go in Vietnam, so no wonder the depth and viscerality of the anti-Asian sentiment dumped at our feet. I would have been almost three years old at the time so I have no palpable memory of those early settling-in years (my parents ended up sending me back to Seoul to live with my uncle’s family until I was five). But what I do know these five decades later, is that the traumatic and anguished experiences of my parents continue to reside within me, woven and embedded into my own memories, created just as easily once I was old enough.

And let’s just say that I was surprised by the “surprise” of some people during the height of violence against Asian (looking) people around the time of early COVID. But why was anyone surprised? Is it because the history and cultural coda of certain populations are not taught in our schools? (This is a rhetorical question). Certainly, history reminds us that this kind of violence towards people who look like me did not begin in 2020. We see how laws and systems of exclusion and subjugation from past centuries e.g. 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act are indelibly ingrained in the political and social tableau of this country, creating climates where menace, rage and anger towards the “others” is deemed acceptable, the norm even.

So if A Temporary Dwelling manages to take a stand against normalized bias and systemic racism, then I am on the right track. But of course, the point of writing poetry (and any book) is to be in conversation with people who are also invested in figuring out what it means to be a human creature living in our century. I want foremost to engage with readers on how to discern and critique messages from the culture in power so that we may be empowered and empower others on how to take control of creating and defining our identities, not the other way around.

I see that I have become distilled into the poet-person I am from all the hours of reading I was afforded as a child, then as a young person, and through these adult years that have led to here. Overexposed, perhaps, by the Western white male canon of my schooling, but nevertheless with the wherewithal to find my kindred poets (some who may be in said canon), from Yusef Komunyakaa, Philip Levine and Louise Bogan, to Audre Lorde, Sylvia Plath, Robert Hershon and Langston Hughes. And so many more kindred spirits who inspire and compel me to write with the understanding that as writers, we must enact and embody the utmost value of poetry: make sense of the chaotic world we have been thrust into as the introspective and retrospective creatures we are.

But I acknowledge that writing to make meaning is both an honor and a burden, as we are witness to as much exuberance and joy as we are to everyday sorrows and insurmountable grief. But we do not shy away from this vital role of documenting and reporting on our living and dying, heeding Denise Levertov’s missive to be poets in the world, who take “personal and active responsibility for [our]words…acknowledge their potential influence on the lives of others” for when “words penetrate deep into us, they change the chemistry of the soul, of the imagination” (The Poet in the World, 1960).

Four years have passed since my mother died in a hospital on Mother’s Day 2020, after months of being hooked up to a machine. I was not allowed to visit her during this time as hospitals were on COVID lock down. How senseless for her life to end this way. I could go to school for a hundred years and still not wrap my head around it.

I was not given meaning, so I had to make it.

From A Temporary Dwelling:

Beautiful Forever

hooked up

to a machine

to make you breath for a month

that is how delicate you became

how transparent your skin

stretched to invisibility

your dark blue veins

traveling above ground

arteries of water on land mass

you became a map.

Jiwon Choi is a poet, preschool teacher, and urban gardener. She is the author of One Daughter is Worth Ten Sons and I Used To Be Korean both published by Hanging Loose Press, as well as Choi’s third book of poems, A Temporary Dwelling, published by Spuyten Duyvil in 2024. She started her community garden’s first poetry reading series, Poets Read in the Garden, to support local writers. You can find out more about her at iusedtobekorean.com.

Jiwon Choi is a poet, preschool teacher, and urban gardener. She is the author of One Daughter is Worth Ten Sons and I Used To Be Korean both published by Hanging Loose Press, as well as Choi’s third book of poems, A Temporary Dwelling, published by Spuyten Duyvil in 2024. She started her community garden’s first poetry reading series, Poets Read in the Garden, to support local writers. You can find out more about her at iusedtobekorean.com.