Review by Ruth Hoberman

Review by Ruth Hoberman

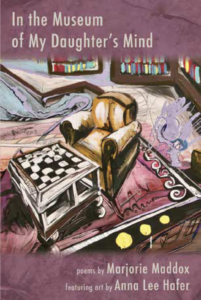

Marjorie Maddox’s most recent book, In the Museum of My Daughter’s Mind, is a (mostly) joyous celebration of prickly, eccentric visions. In 2018, Maddox tells us, she and her daughter, Anna Lee Hafer, a visual artist, drove three hours to Baltimore to visit that city’s American Visionary Art Museum. Some of the works they admired there—by Margaret Munz-Losch, Antar Mikosz, Ingo Swann, Christian Twamley, and Greg Mort—appear in Maddox’s book, as do Hafer’s own paintings, and two photographs by Karen Elias: each is paired with a poem Maddox wrote in response. The result—a swirling stew of words, lines, and colors—insists that the most ordinary space or scene can swing us abruptly into other worlds, working as an “unexpected hinged/opening to awe,” as Maddox writes in response to Mort’s 2015 painting “The Watcher.”

Mort’s painting depicts a man dressed in jeans and a white shirt about to step through a doorway into star-strewn outer space. Join him, Maddox’s poem urges. Step with him “into vision.” Ingo Swann’s “Highways, 1976” feels similarly surreal: a realistically depicted road stretches into the distance mirrored by another road above it, apparently realistic but made from darkness and stars. “From here he sees there,” Maddox writes in the accompanying poem: “one road running above the other.” So let’s go, Maddox suggests in various ways throughout this collection: “Climb in./Let’s go for a spin.”

Hafer’s paintings strike me as less surreal than expressionistic: through colorful swirling lines we discern cityscapes, suns, houses, rooms—all just a bit out of kilter, inside intersecting with outside, perspective askew. I thought of Münch and of Van Gogh, who’s evoked in one of Maddox’s poems, responding to Hafer’s “Metaphysical Vault”: “Beneath this dome of sky,/breathe,” the speaker urges. Visual and verbal images serve as lenses through which we’re invited to see the world differently:

Ah, the awe of collage:

hands unlocking mind’s focus

and filter: textured lens, layered

landscape, sight/insight of day,

paint-studded starry, starry night.

The shifting “a” sounds of “Ah, the awe of collage” exemplify Maddox’s method: her use of repetition and difference to shift us from familiar landscape into “starry, starry night.” There’s something wonderfully generous about these poems—their assumption that we are all capable of this movement toward vision and their careful use of language to help us get there.

Maddox frequently harnesses the repetition of received forms like pantoum, sestina, and villanelle to evoke the spiraling, whirling lines of Hafer’s art. Spirals invite us to ascend even as we circle back on the familiar. That’s precisely what these poems do—each repetition transformed and energized by the variations that follow.

Perhaps the most moving poem is “Swirl,” a pantoum (in which the first and third lines of each four-line stanza return as the second and third lines of the next). Responding to Hafer’s painting, also named “Swirl,” Maddox writes:

Look closer. This is not a textbook, but a person.

This is not a painting but the poem of someone’s mind,

her mind: new or worse depression.

Beneath the surface of harmonious balance,

this is not a painting but the poem of someone’s mind.

Thoughts about suicide or dying

beneath the surface of harmonious balance.

Italicized quotations from medication labels, along with the repetition demanded by the form, evoke entrapment: “weeping you can drown in, almost did”:

This is not a final exam. This is a daughter,

who slipped beneath the surface, but rose up

from weeping. You almost drowned in it. Did.

That “you” directly addressing the daughter breaks through any pretense of detachment. There’s a lot at stake in this poem—in this project. “This is a life of treating depression, both/a painting and poem—complicated beauty of mind/beneath the surface of harmonious balance.”

Words and images can pull us down—when they take the form of diagnoses, labels, or societal constraints—but they can also spin us upwards, as the book’s final poem, “Wild Rest,” suggests. Hafer’s painting is of an armchair surrounded by letters, numbers and bookcases. Maddox’s poem is a sestina, another form that relies on repetition—of the same six end-words arranged in varying configurations throughout seven stanzas. The familiar armchair, like the repeated end-words, can nonetheless whirl us into elsewhere. Relax, she tells us: “before the familiar view—a wonder/really, the paradox of renewal, its wild/witness of a world gone wild/with vision….”

A professor of English and Creative Writing at Lock Haven University, in Pennsylvania, Maddox has published short stories, several books for young people, and fourteen books of poetry. This is her second collection of ekphrastic poems. In the Museum of My Daughter’s Mind pops with synergy: between poems and images, between mother and daughter, between poetic speaker and reader. “Follow the inner workings of the mind,” Maddox writes in “The Choice,” the book’s opening poem: “Click open/possibility.”

In the Museum of My Daughter’s Mind by Marjorie Maddox

Shanti Arts Publishing 2023 $22.95 [Paper]

ISBN 978-1-956056-74-7

Ruth Hoberman is a professor emerita of English at Eastern Illinois University. Since her 2015 retirement, her poems and essays have appeared in such journals as Smartish Pace, RHINO, Comstock Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, and Ploughshares.