Selections from Girlfriend

Girlfriend is a collection of poetic prose short-shorts about my relationships with girl and women friends from childhood through my present elder years. When I showed my esteemed yoga teacher Genny Kapuler what I had written about her, she said, “I feel honored to be one of the beads in the Mala, one of your sisters.” I like to think about it like that, as a meditation, as a string of beads. Included are friends, family, teachers, mentors and certain women authors and characters who were meaningful to me at important moments and turning points in my life. The writing wavers between poem and prose, like a collage of consciousness, I think, following the way my remembering mind intersects with my poetics.

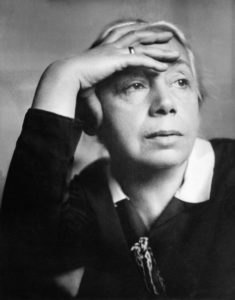

Käthe Kollwitz

The worst of it all is that every war already carries within it the war which will answer it. Every war is answered by a new war, until everything, everything is smashed.. . .That is why I am wholeheartedly for a radical end to this madness. (Letter to Ottilie, Feb 21, 1944)

New Year’s Day 2024. With everyday news of more war deaths from the Ukraine and from Israel/Palestine, I sit quietly with your writing and prints. My generation also suffered from war loss–in Vietnam, my brother was shot and my first boyfriend lost both his legs. I first saw one of your self-portraits in the German Expressionist room at the DIA, maybe in ‘73 and I’ve kept your work near me ever since. The loss in your face reminds me of my Swiss grandmother who came to help my father take care of us after our mother died. You were born in 1867, she was born in 1894, young enough to be your daughter. In response to loss, she crocheted, gardened and cooked. I watched her turn inward as her body collapsed in the chair in our living room. After your son Peter was killed in World War I, you wrote in your diary, “Then came the war and turned everything topsy-turvey. Knocked down flat on the ground. Half alive and half dead, one crawled in silence, living a humble life drenched with suffering. One rose to one’s feet very slowly.” You worked through your grief with your art, art for the public, print media and two stunning sculptures of grieving parents installed at the war cemetery in Flanders. Your husband was a doctor serving workers in a clinic in your house in Berlin. As those who were poorly paid and lived under harsh conditions came and left, you counseled and sketched them. Because of your anti-war art-activism, the Nazis refused to let you show your work anywhere or teach for the rest of your life. After the Gestapo came to your house, you and Karl carried vials of poison in case they tried to arrest you. In your woodcut, “The Mothers,” the women form a circle wrapping their arms around their children, as if to say, You will not have them. War. Death. We will die with them. In unity. They will not be torn from us. In the shape of a tombstone. Then you lost a grandson in World War II, and a few weeks before Germany surrendered, you died of old age. Your son, Hans, describes you in his last visit. “Shattered by age though she was, she seemed like a queen in exile; she had a compelling kindliness and dignity.” In your lithograph, “The Call of Death,” Death taps you on the shoulder. Her hand is delicate. Your hand is suspended as if in the middle of saying something to someone. You turn and look over your shoulder. Oh, it is only you . . .

Left: Käthe Kollwitz, 1928, photo by Emil Hoppe; right: “The Mothers,” woodcut, 1922-23

Ferne

You taught me how to fold towels and sheets. You were very organized, everything in its place. You taught me how to separate the dirty clothes into various piles. You taught me how to hang clothes on the clothesline. When you were taking care of our new baby, I took care of my baby doll. You taught me how to line up cans of soup in rows in the cupboard. You taught me how to clean the woodwork and you paid me two cents for each wall. You taught me how to cut out little circles and stitch along the edges, pulling them into pouches, then flattening and sewing them together. You invited all the little girls in the neighborhood to our quilting party. When I was very young, you were beautiful and energetic. When I was ten years old, you were weak and skinny to the bone. The phone was always ringing. You had three sisters and many friends. You were a Sunday school teacher and a Cub Scout den mother. Women in the neighborhood would come over for coffee; you’d chat, smoke and talk in the kitchen. When I was very young, we dressed up and played cocktail lounge on our coffee table. When I was a little older, you told me secrets about your life as if I was your friend—a first husband, your boyfriends, your discontent with my father. After winding my hair into pin curls, you patted my head and sent me to bed. When I was worried whether I really believed in God or not, you reassured me that if I was worried, then I had nothing to worry about. Be kind. Be helpful. Go to church. You taught me how to wash and dry dishes. How to boil a potato and mash it. How to make a hamburger. After you died, I’d pretend I was sick and stay home from school looking through photo albums and watching old movies from the ‘40s. I skipped out of Sunday school for good. I remember people talking about the size of the crowd at the funeral parlor. I remember hearing my father say, They had to open another room for Fernie. I refused to recognize the stepmother who arrived a year later with a very strict set of rules. No one could replace you. As an older adult, I researched your life and times and wrote a book about you. This morning, I realized I haven’t been thinking about you that much lately, my life as a child now like a small shrinking room filled with blue sky, and I’m on my bike pedaling down the street. It’s 20 degrees today. Outside my window the sun casts a light orange over the towering oak tree as its branches waver in the frigid air. The forecast for Tuesday is ten degrees warmer, then on Wednesday, even warmer.

Ferne, 1941; Barbara, 1960

Ginny

You and Patti were always close; you grew up sharing a bedroom and later you both became nurses. Your life wasn’t easy in our family. With the loss of our mother and then a stepmother, you were the one in the middle, and you often felt neglected. You weren’t rebellious, except in very minor ways, common to us all—eating all the Girl Scout cookies, kissing the boy down the street, cutting up Dick, Jane and Sally books. Once when you were about seven years old, you were angry, so you put some clothes in your doll’s suitcase, hooked it up on your bike, announced you were running away, and then you rode around the block several times. Of the three of us, you were the first to get married and have a baby. I tried to help, but I had no experience with babies. When you had postpartum depression, I found you walking in a desolate area of the city. I brought you home with me. When I was pregnant, and you were planning at the spur of the moment, an all-night drive down south with your baby to see a friend, I went with you. When our daughters became close, you often took my daughter overnight. We had our share of arguments, but none of them were long lasting. When we moved to New York City, I was absent from most of the family gatherings. You stayed close to Dad and Jean, though, and when they were near the end, you did most of the work taking care of them, as daughter and nurse. You have an extended family in your duplex—you, your high school boyfriend lifelong husband, your daughter and grandson. Over the years, you’ve had a lot of trouble with your body, surgery on your ankles and your hip, auto-immune pain, but you have been resilient and humorous through it all. As children, all four of us took care of each other; and even if our lives are very different now, we are still there for each other.

Left: Ginny 1958; middle: Barbara and Ginny, 1964; right: 1977

Patti

When I was nine and you were three, you followed me around and I’d say, Patti, get me that, do this, do that. When we were a bit older, and our mother was in the hospital, you thought I was your mother, but I was only a kid. I made up scary stories at night and you repeated them in kindergarten. Your teacher called me to talk after school. She was worried. Would I tell my father about the stories? A few years later, our stepmother arrived, and I fought with her, but you were too young to fight. As a young teenager you took quaaludes and pretended you were just tired. I begged you not to take them. One night I left home with a boyfriend. Soon after Bobby went to Vietnam and Ginny got married. You were left behind with Jean who wouldn’t let you wash your hair or your uniform for your part-time job as a nurse’s aide in the hospital. It was as if she was living in the middle of the depression, but there was no depression, just a small envelope of power. You did well in school, played the guitar, went to Europe, then off to college as far away as you could go and still be in Michigan. Then you married and we both had babies. After Allen and I broke up, my children came to your house for holidays, and you took Mook in when he was a teenager and needed to get away from the city. You flew to New York to help me when Allen was dying. After your thirty-year marriage ended, you were lost for a while. You said you felt like a plant ripped out of the soil. You moved, retired, planted flowers, planted a lot of flowers, and then you found another job downstate. I liked being single and independent together with you, even just on the phone or in the summers, but now, five years later, you’re back in the northern woods, moving with the winds of Lake Superior, married again, hiking and kayaking. When you were living alone, you used to say, “All of you, my brother and sisters, can come and live with me when you’re old.” But now we’re getting old, living with our own histories, spread out and rooted in the places where we chose to go, many miles apart.

Left, Patti and Barbara, 1962; middle: 1973; right 2015

Linnéé

After you were born, Allen and I bought an old house with a room for you with rose wallpaper. You loved reading and looking at books, but sometimes you were a little tot with attitude. You’d sit on the potty and demand more and more books to read. Your nursery schoolteacher said, “Tell her to get them herself.” After that, you miraculously potty trained yourself. For three years you woke us up in the middle of the night wanting company, but on the day Michah was born, you both slept through the night. You two were always close, even though he used to tease you. Now you live with all boy energy, two teenage boys and a husband. As a child (and now as an adult) you were articulate, beautiful and vibrant. And you always loved to draw and paint. You stood up for yourself when you were wronged, and for your friends, too. As a teenager, you were impatient with teachers who weren’t really teaching, and now you are a middle-school teacher and a student advocate. You loved your kindergarten and first grade teacher, Mrs. Snyder. And your married name is Snyder! You are a do-er, like me, keep busy, take care of everyone. I worry sometimes that you don’t take enough time for yourself.

You didn’t like it when Dad and I split up, and we moved out of our house into two small apartments, and you didn’t like it when I left you and Michah in Detroit, so I could look for an apartment and a job in NYC. It was the only way I could resettle us. And in retrospect, I think it was the right thing to do. For a while we had to deal with tight funds, with me working so much, and then with Dad’s illness. You didn’t like a few of my boyfriends, and you were usually right on that account. Sometimes I was sad, sometimes irritable and short tempered, but I always loved you. I couldn’t give you what you are giving your children, but I helped both of you make it through school, and if you got in trouble, I got you out of it, negotiating with teachers, finding new schools, talking with you to help solve your problems. Once you were reading Charlotte’s Web and you wrote for your school assignment. “Her mother was a cooker. My mother is a writer.” You probably got a lot of strengths from our alternative life—your creativity, your love of children and family, your call to teach, your outrage at unfairness. When Dad was dying, I played Louie Armstrong, “What a Wonderful World” and when you married Greg, you asked me to dance with you, in Dad’s place, and you had the DJ play that same song. No matter the difficulties and losses in life, it is all so stunningly beautiful, isn’t it? Remember when I took the train out to South Hampton to your dorm to bring you a pumpkin cheesecake for your birthday. And while I was there with you and your friends in the dorm, the phone rang two times. It was Dad checking up on you.

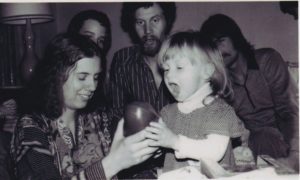

Left: Barbara and Linnée on Linnée’s 3rd Birthday, So happy with Mr. Potato; in back, Richie Hartigan, Allen Saperstein and Bob Henning; Right: Barb and Linnee in 7th Street Apt, 2002, photo by Michah Saperstein.

Read more by Barbara Henning – Selections from “Girlfriend” (Part One)