Review by Dayna Patterson

Review by Dayna Patterson

Many poets are familiar with Trish Hopkinson, the “selfish poet.” She is not just a supremely skilled poet herself, but a friend to poets, guiding writers as they navigate the complex Poetryverse through her website, trishhopkinson.com. Here, novices and experts alike can find submission tips and tricks, interviews with editors about what they’re looking for, lists of feminist lit mags, chapbook/book contests that don’t charge submission fees, etc., etc. It’s an astonishing collection of poetry resources, generously shared and maintained by Hopkinson. Once in a while, she will tootle her horn, sharing publication news about her poems. Selfish, indeed.

In light of this “selfishness,” many will be delighted to learn that Hopkinson’s first full-length collection, A Godless Ascends, will be released by Lithic Press in March 2024—on March 19th, to be exact, just in time for the vernal equinox, which seems elegant for a book about the seasons of a life. The narrative arc of these poems follows the birth and growth of a central speaker: her maturation and budding sexuality, her evolving relationship with faith and family, and her mothering through pandemic and private catastrophe. Throughout the collection, readers can’t help but root for this “godless” to ascend, for the speaker to rise out of her circumstances, the poverty and dysfunction of her family, to arrive at her own self-knowledge and power, and to pass that love and resilience on to her children despite overwhelming adversity.

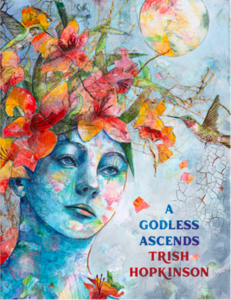

In 2019, I reviewed Hopkinson’s fourth chapbook Almost Famous for Tinderbox Editions here, and I was delighted to discover that many of those poems are included in her new collection, mostly in the first section. (I’m a big fan of repurposing chapbooks into full-lengths.) The book is divided into four sections, each section beginning with a poem about a “she-god” and a companion water media painting by Nancy Smith. While not explicitly naming seasons, either in the she-god poems or the section break titles, there is certainly a seasonal feel to these sections and accompanying pieces by Smith. One of these paintings graces the cover of the collection: a woman’s face gazes pensively upward, and on her head is a crown of tangerine and scarlet lilies. Two ruby-throated hummingbirds seem intent on searching for nectar in the woman’s flower crown, and in the upper right corner a full moon hovers in bright summery colors.

This she-god in her lily crown also appears at the beginning of the second section, when the speaker has grown from an infant into a young woman, into her summer, and into her blooming sexuality. The last poem of the first section, “Promiscuity,” ends with the central speaker exploring her sexuality, adding stitches to her belt, until she encounters her religious mother’s reaction:

The division in this contrapuntal poem visually depicts the rift between mother and daughter, and even though the speaker rips the seams and irons patches over them, the emotional distance remains.

The mother and speaker-daughter become further differentiated in the collection’s second section, as the speaker eventually rejects the shame of purity culture induced by her mother’s disapproval. Part of this pivot occurs because the speaker figures out, in the poem “Dragonfly Daughter,” that she was born seven months after her parent’s wedding. Her mother’s hypocrisy is stark. The speaker’s metamorphosis into adulthood and toward self-actualization, is underscored by the various forms the speaker inhabits in this section: in addition to a dragonfly, she becomes a beetle, a hummingbird. She is a screech owl who “cannot eat again until the remains are let go” (44). In “Ascent,” the speaker cuts ties with bloodlines, insisting on change:

[ . . . ] sparrows tumble from my throat,

let loose, flutter around the room,

peck the floorboards for seeds, flick their beaks

and bony tongues at gnats swarming

a bowl of softened pomegranates. I clasp

my jaw and refuse to let them

back in (41)

The speaker’s mantra of transformation and ascent continues in “I Do Not Wait”:

I ratchet skyward,

take my place at the sun’s table,

lifted by turquoise bone & bladed wings.

My scarab shell snubs boot heels,

scurries and flutters solo

& yes, I possess myself.

I will not be held in a fist,

pinned or stuffed in a case,

pierced beneath glass. (42)

The speaker is powerful, possesses herself, eats at the sun’s table, refuses to be contained in any way. Her transformation is almost mythic, goddess-like, which might prompt readers to wonder: Who is the “She-God” that appears at the beginning of each section? One possible answer is that she’s a manifestation of the central speaker herself. In She-God’s first appearance, we learn:

—she birthed two

no three—

if she chooses to

count herself

& she does (9)

The first two poems of the collection contrast wildly: this She-God is powerful and full of agency, even giving birth to herself, while in the second poem, the mother and speaker are under a male doctor’s power. The She-God slices through a bull’s sex like cheesecake (a symbolic castration of patriarchy), while in the second poem the doctor anesthetizes the speaker’s mother and extracts the baby with forceps (a symbolic—and very real—birth into a male-dominated world). The poems in this collection progress to show the speaker’s growth, her transformation into herself and her agency over her own body, into the She-God of the opening poem.

In the second She-God poem, “She-God // Nocturne to the Uterus,” the speaker-goddess condemns the uterus as a “venous devil” and a lustful organ, clearly voicing the internalized shame instilled by her mother’s disapproval of her sexuality (27). But by the third She-God poem, after the second section’s various iterations of the speaker’s metamorphosis, we encounter a very different tone. In “She-God // A Godless Celebrates Vernal Equinox,” the speaker-goddess has left behind shame and the denigration of her own body. She apologizes for nothing, confesses to no one: “there are no confessions / by these hips / / no repentance for these breasts” (49). This shift mirrors the central speaker’s shift in her own self-perception and self-affirmation that occurs throughout the second section, a kind of self-love the speaker tries to pass on to her offspring.

In the collection’s third section, “Things to Tell My Daughter,” the focus of the narrative arc centers on the speaker’s children, specifically her firstborn, her daughter. It includes poems like “Calve,” “Ode to My Mess,” “Ripened,” “Empty Nest,” and “Our Lady of Lexapro in 2020.” We rediscover and recognize in these poems the realness, the messiness of motherhood. In “Ripened,” fruit (and children) “grow and ripen / without permission” (61). The “Empty Nest” doesn’t lead to mere loneliness and acceptance, like readers might expect, but a worse case scenario of pandemic, environmental catastrophe, and mental health crisis.

The fourth & final section, “Bone Music,” leans into the difficulty of parenting adult children, who, despite being grown, remain vulnerable in an unpredictable world. The section opens with a She-God poem, “She-God // The Creator,” in which the speaker-goddess dwells on the drama of birth, remembering that “splendor and pain,” “both creator and birthed / remember the after” (71). In the poems that follow, this She-God poem acts as a precursor to the speaker’s son’s horrific biking accident that nearly takes his life, the mutual pain felt by mother and son during recovery, and the son’s “resurrection” back into health, his rebirth into life. In the last poem, the son throws a “Resurrection Party” for himself, dressed as Christ “with death metal makeup,” which makes the speaker a kind of Mary, who has watched her son suffer and, miraculously, survive (96).

In one of my (many) favorite poems in the collection, “Calve,” Hopkinson wonders if a glacier is a kind of mother who feels each calving:

Does the glacier feel the breaking off?

Does her head spin with confusion

at separation or does she push

with such tenderness, such reaching,

her fingertips gently sliding along

the palm of the infant’s tiny hand

until they no longer touch?

Does she pull the rain to her breast,

suckle it ’til it becomes part of her

once again. Does she ever really let go? (54-55)

That last question echoes throughout Hopkinson’s parenting poems. It haunts the hallways of the hospital alongside the speaker who doesn’t leave her son’s side. It’ll ghost readers, long after they put Hopkinson’s book down and proceed with the intense sweet-sorrowful work of raising vulnerable human beings in the world.

A Godless Ascends by Trish Hopkinson

Lithic Press, March 2024

ISBN 978-1946-583-321

72pp / paperback

Dayna Patterson is a photographer, textile artist, and irreverent bardophile. She’s the author of O Lady, Speak Again (Signature Books, 2023), If Mother Braids a Waterfall (Signature Books, 2020) and Titania in Yellow (Porkbelly Press, 2019). Honors include the Association for Mormon Letters Poetry Award and the 2019 #DignityNotDetention Poetry Prize judged by Ilya Kaminsky. She’s the founding editor (now emerita) of Psaltery & Lyre and a co-editor of Dove Song: Heavenly Mother in Mormon Poetry.