Review by Linda K. Sienkiewicz

Review by Linda K. Sienkiewicz

“There were herbs in the Waters of Massasauga swamp that could be rendered into medicines for just about every affliction: yarrow and plantain for bleeding wounds, elderberries and boneset for flu, willow bark for fever, and foxglove and dandelion for too much pressure in the body… and if you asked Herself to make a water or tonic to fix you, she would study the veins in your hand and the whites of your eyes while considering what kind of poison to add… Bloodroot? Snakeroot? Rattlesnake venom, if she had it?” (41)

The Waters is a spellbinding and brutal story about about an aging herbalist, Hermine “Herself” Zook, and her granddaughter, who live in a cottage on a marshland island in a farming township in rural Michigan. The farmers, like the herbalist, struggle to find balance the modern world, a recurring theme. Men are uncertain where their loyalties should lie. Rural folk are wary of hospitals and modern medicine. The people of Whiteheart resent Hermine precisely because they need her potions and poisons; others vilify her for the cure that starts a woman’s monthly bleeding again. They spy on her, fire guns into the Waters, and argue over whether she’s a savior or witch.

Hermine has raised three women on her own: Primrose, left in a basket for Hermine to adopt, escapes the Waters for California; Hermine’s birth daughter, Molly, rejects her mother’s folk medicine to become a nurse; the youngest, Rose Thorn, actually Primroses’ daughter, takes life as she pleases. The townsmen revere Rose as a goddess as they longingly watch the town’s most eligible bachelor, Titus Jr., court her. Rose, a restless soul, chafes at being a farmer’s wife.

After a stay with Primrose in California, Rose returns with a newborn. All she will tell anyone, besides Hermine, is that her baby is not Titus’s. Under Hermine’s tutelage, the child they nickname Donkey thrives on the lush, mythical island. Unschooled, she studies math on her own while she tempts disaster, believing she can communicate with the Massasauga rattler she accidentally let loose in her grandmother’s house. She longs for her mother, unable to understand why Rose comes and goes.

Now sitting up in her granny’s bed, Donkey felt the slithering of creatures moving under the island fog as though across her bare skin… She was eleven years old and five foot eleven inches tall, old enough and big enough to sleep alone, for crying out loud, according to Molly, but the little bedroom off the kitchen was lonely without Rose Thorn. Every middle of the night when Donkey heard the snoring that meant Herself was done tossing and turning over other people’s problems, she slipped out of her sheets…. and padded down the hall to lie beside the big body, to inhale the scent of lavender and holy basil, to count those voluminous breaths and resounding heartbeats. During the day, Herself was stern and commanding, spoke little and never flattered, just mumbled her irritation over food and medicine and the brutes of Nowhere, but anybody who slept beside Hermine knew she became luxuriant in her joints, that she relaxed her muscles and released herself to the colorful, tender, loving dreams that Donkey glimpsed in her own sleep. While Donkey’s personal dreams were of animals, Hermine’s were often of the island’s trees and plants and soil, though often she shared sensual visions of her difficult daughters… (59)

Donkey tries to make sense of the ways of ordinary men who fumble in their uncertainty and the women who love them or deny them love, and the ramshackle lives they hack out for themselves. Campbell writes, “Times change faster than the people in them” (94). As mounting tragedies and discoveries shift and widen Donkey’s world, her awakening clashes with the eccentric Zook women as they too struggle to love, understand, and forgive. The deadly snake haunts and taunts every character, reappearing throughout the book, and most terrifyingly at the story’s end, reaffirming we never can escape that which we fear most. Donkey learns that heroes are fallible, and power comes from within.

The writing is dense, ranging from sweepingly cinematic views to painstaking details that draw you ever closer to the land, the town, and its idiosyncratic people. This is fiction to lean into, to absorb, like a sweet morning fog. Do not rush. You might miss “the swamp mottled pattern, the triple-thickness of the body under the bed” (82) or mistake the identity of the gaunt “ghost” in the Waters.

Bonnie Jo Campbell is the author of six works of fiction, including American Salvage, finalist for the National Book Award and National Book Critics Circle Award, and Once Upon a River, a national bestseller. She is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, AWP’s Grace Paley Prize for Short Fiction, a Pushcart Prize and and Eudora Welty Prize. She lives outside of Kalamazoo, Michigan.

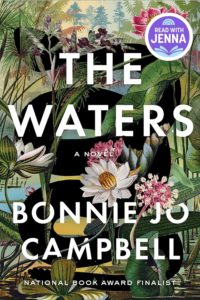

The Waters by Bonnie Jo Campbell

W.W. Norton & Company, 2024

Hardcover $27, Kindle $14.99

ISBN: 978039324843

Linda K. Sienkiewicz’s poetry and short stories are widely published. Her novel, In the Context of Love, was a finalist for multiple awards, and she received a poetry chapbook award from Heartlands Today. Sienkiewicz’s fourth poetry chapbook, Sleepwalker, is about the suicide of her eldest son. She also wrote and illustrated a children’s picture book, Gordy and the Ghost Crab. Her MFA is from The University of Southern Maine.