Review by Jennifer Martelli

Review by Jennifer Martelli

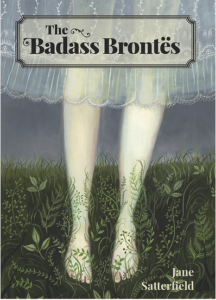

Lately, I’ve been obsessed with groups of three: triads, tercets, triplets. There is a wyrd sisterhood about the number, mystical and yet as sturdy as a wooden stool. Thomas De Quincey, in his book of essays, Suspiria De Profundis, writes, “and they are three in number, as in the Graces . . . the Parcae . . . the Furies . . . even the Muses.” So when I read Jane Satterfield’s masterful collection, The Badass Brontës, I was smitten. In “Gigan for a Pandemic Winter,” Satterfield writes,

Once three sisters watched the world

turn its direction, wrote through geographies of grief.

That shattered silence—a glove thrown on the ground.

Satterfield throws down the gauntlet, raises the stakes of the story of the three surviving and famous Brontë sisters—Emily, Charlotte, Anne—by weaving them poetically into today’s world, into the speaker’s world, and in the most evocative way, into my world.

Jane Satterfield’s book is much like a braid: three hanks of hair weaving and intertwining that create a tight and true entity. As with ancient triads of women, the sisters’ names change; Emily, Charlotte, and Anne Brontë become Ellis, Currer, and Acton Bell. Even their last name transforms over time, “an incantation . . . Bruntee, Prunty, Brunty . . .” The Badass Brontës includes extensive notes and epigraphs, as well as a “Who’s Who in Brontëworld.” Here, the reader learns of the sisters, known (most famously) for writing Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre, and Agnes Grey. But this section is also a registry of their losses: their brother Branwell, their mother, their sisters before them, as well as Emily’s companions/familiars, “Keeper, a mastiff; Nero, an injured hawk rescued from the moors; Tiger, a tabby; Adelaide and Victoria, a pair of geese.” I love a book that includes bonuses, much like extra tracks on a CD or a director’s cut. As a reader, I plumb the topic with the writer, who is inhabiting the world of Victorian England, as well as the present-day United States.

Satterfield’s language and poetic forms hold the braid together. She stitches a “thunder dress,” much like Emily’s with its stormy pattern, “affecting a fix with fine tucks.” The proem, “Reading Emily Brontë by Long Island Sound,” immediately begins with this stitching of time. Satterfield writes

Your dress was a welter

of thunder clouds & lightning bolts—

Today I’m gauze & flutter sleeves.

Satterfield then rolls up her political sleeves to confront the fraught issues of our time through the lenses of the Brontës. Satterfield draws parallels between the Covid-19 quarantine and tuberculosis of the 19th century; she employs modern pop culture forms, like internet quizzes in her poem, “Which Brontë Sister Are You?” “The Consequences of Desire/Brontë Bodies” speaks to bodily autonomy. A gorgeous piece that asks the reader to “consider medicinals, this for the pain & this for other courses missed . . .” Embedded in the Brontë landscape where Emily with her tabby, the “hedge witch,” requests a woven “nettle dress,” the poem speaks to the choice of ending a life, and of ending a pregnancy. “But what part,” Anne asks, “did my own body’s passage play in my mother’s leaving, those months / of protracted pain, her womb inflamed until the toxins clenched her heart?” As I read this poem, I couldn’t help but think of the recent and tragic case of Kate Cox in Texas, who nearly died because she was not allowed an abortion; her body and her state became prisons, coffins.

One of the questions I ask myself when reading a heavily-themed or a project book is: what’s at stake for the poet? Jane Satterfield connects, not only politically, but emotionally to this landscape, the land of the speaker’s childhood, where, in her epistolary “Letter to Emily Brontë,” she tells her,

Once I lived within

a few miles of those heathered moors

where you worked out plots that swirled

around the heart’s tenancy. I remember

high, cold clouds, the wind wild

at Withins. Today I practice patience,

As I was reading this collection, I had to have Kate Bush’s “Wuthering Heights” playing on a loop (my own familiar, Maria, would just look at me by the fifth time around). Satterfield’s villanelle, “The Most Wuthering Heights Day Ever” is the perfect form for a book that weaves time and place. The villanelle is an old poetic form (once a dance) that requires repetition and circularity. Satterfield weaves the lines “and love it wildly—the wind & weather / synced for the most Wuthering Heights Day ever” throughout the poem. Like the dance recreated world-wide, The Badass Brontës transcends place as well. In “Sestina for Hiraeth, with Titles of Plath Poems from Early 1963,” Satterfield writes,

realms, the Welsh gave us hiraeth, a word that’s mystical,

the longing for a homeland you can’t return to—no word

my Midlands-born mother knew . . .

Using another obsessive form—the sestina—Satterfield evokes images of Emily’s longing, of “her exile eased by memory and her sister’s kindness,” but also, of the speaker’s longing for her mother, and of course, Plath’s own fatal homesickness. I was bewitched by the six end words that anchor a sestina—fog, mystic, child, totem, kindness, words—all of these parts of Brontëworld.

I also ask: what’s a stake for the reader? For this reader, it was the three sisters. I don’t cry when I read too many poems (exceptions: Elizabeth Bishop’s “Poem” and Wanda Coleman’s “Dear Mama (4)”). “Crow Hill Postscript” made me cry. In the voice of Charlotte—the middle and last sister to die—we hear of her breathtaking and tubercular grief over losing Emily. In the poem’s epigraph, Charlotte Brontë wrote in a letter, “I could hardly let Emily go—I wanted to hold her back then—and I want her back now—.” As the middle of three sisters, losing one of them would be like losing the leg of that wooden stool. Charlotte hears Emily, “Ghostly sounds are what’s left to me—her laughter and clatter / in the kitchen, Tiger teasing at her heels.” In “Archival,” the speaker dedicates the poem, “For the sister I never had.” This loss is so real, the speaker must “summon / the spectral—.” The book, then, is revealed as a love story, a

desk box like a heart

carried out

in good weather,

or tidied at night—a heart &

what it holds

or hides—open it:

out flies a wish—

Jane Satterfield’s mastery of the mechanics of poetry, her weaving of time and place, and the expressions of sisterhood affected me deeply, profoundly. She braids a strong rope of history, literature, and love. “Because the bracken I brought in from the heath / festers under glass, an architecture of grief,” Satterfield writes in “Rewriting Emily,” and certainly, the work here exists in my world, in the speaker’s world, and in the realm of Emily, Charlotte, and Anne Bronte. Jane Satterfield’s, The Badass Brontës, assures us that “it’s better to learn dark / sonatas, the heart’s own haul of grief.”

The Badass Brontës by Jane Satterfield

Diode Editions 2023

ISBN: 9781939728579

Jennifer Martelli (she, her, hers) is the author of The Queen of Queens (Bordighera Press, 2022) and My Tarantella (Bordighera Press), awarded an Honorable Mention from the Italian-American Studies Association, selected as a 2019 “Must Read” by the Massachusetts Center for the Book, and named as a finalist for the Housatonic Book Award. She is also the author of the chapbooks In the Year of Ferraro (Nixes Mate Press) and After Bird, winner of the Grey Book Press open reading, 2016. Her work has appeared in The Academy of American Poets Poem a Day, The Tahoma Literary Review, Thrush, Cream City Review, Verse Daily, Iron Horse Review(winner, Photo Finish contest), and Poetry. Jennifer Martelli has twice received grants from the Massachusetts Cultural Council for her poetry. She is co-poetry editor for Mom Egg Review and co-curates the Italian-American Writers Series. Jennifer Martelli received degrees from Boston University and the Warren Wilson M.F.A. Program for Writers.