Review by Julia Lisella

Review by Julia Lisella

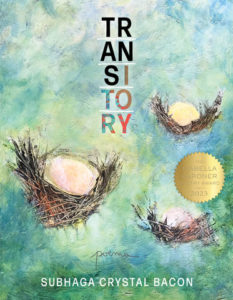

In Subhaga Crystal Bacon’s fourth collection of poems, Transitory, an epigraph from Carolyn Forché instructs: “‘Poetry of witness’ . . . doesn’t mean to write about political matters; it means to write out of having been . . . incised or even wounded by something that happened in the world.” What a gorgeous way to begin this heartbreaking tour through the year 2020, a deadly year in the U.S. for transgender and gender non-conforming people, though sadly, not an exceptional year according to the Human Rights Campaign Foundation. Bacon stands both inside the torrent of the 44 reported deaths in this docu-poetic exploration, as she has been “incised” by the transphobia that leads to systemic violence herself, as she tells us in the opening poem, “Cautiously Watching for Violence: August 2020: the month of no murders of trans people.” And she stands quietly outside as well, navigating the news for us, as witness, as eulogizer, steadily enraged. As she says in “Brook, 32nd in October”: “I carry the weight of them. The shards / of their broken lives in my heart / like bullets, like knives, like fire” (63).

As with all strong docu-poetics, Bacon lets the actual events craft a shape to this telling. Some poems read as Muriel Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead, with language taken directly from police reports. Others are more mediated as the poet addresses the figures she elegizes. And still in others, the victims speak, addressing us, addressing their assailants. Bacon also makes provocative use of forms such as the villanelle, sestina, and the pantoum—end words and slightly shifting alternating lines replicating the relentless quality of the violence and hate, as in “Selena Reyes-Hernandez, 37, Chicago, IL, May 31” (31). In this story, Selena is killed by the 18-year-old who goes home to have sex with her and who returns with a gun. The brutal banality of this hate for the other is made clear: “So he went home for the gun and came back to shoot you again, then again, / to kill you Selena because who you were, he said, made him mad” (31).

The most striking theme about the murders Bacon recounts and the lives of those we have lost is how threatening freedom seems to those who kill, so threatening they must not only kill the person, but deform and destroy the victims’ bodies before the killing. The titles and epigraphs both document and eulogize each life, but also strive to reconstitute the humanity and physical presence of each person. Nearly each poem in the collection begins with a centering title: the murdered person’s full name, age if known, city of death, and date. And then, many of the poems open with an epigraph that is a documented line from the assailant or the murdered person, or something spoken by a friend about that person. In the sestina “Marilyn Cazares, 22, Brawley, CA, July 16” the epigraph reads “She was strong and she would look anybody in the eye and say, ‘I’m very proud of who I am.’ (47). In this poem, Marilyn’s courage to live her truth is fully matched by her Aunt Lorissa’s love and pride in her as “niece”: “She told the world about your painful flowering / from a boyhood of taunts and hurt.” (48). In these epigraphs, the simplicity of the words friends use to describe their loved ones becomes part of the elegance of the intimacy of the poems. But likewise, the hateful words of the murderers or the deadnaming or misgendering words from a police report bind the tellings in our ugly history of hate.

One of the most commendable aspects of this collection is its balance between two crucial elements: the need for the witness to get out of the way of the event, with the need for the witness to become our singular guide through this unfathomable hate and violence. One example of the way Bacon so deftly negotiates this is in the poem “Johanna Metzger 25, Baltimore, MD, April 11” (24). The poem addresses Johanna’s mother Christine who the poet has researched through Google and Facebook—the poems insist that it is easy to know these people and their families if we only look, to know their lives and circumstances, but they continue to be misread, misunderstood, and these misreadings, as Johanna’s mother Christine does in her mourning, only seeing her as the “son” she lost, constitutes another kind of violence. Bacon uses black-outs over the deadname of the “son” so that only the name Johanna is offered to her readers.

While every person in this collection is envisioned with the dignity and respect they were often denied in their lifetimes, one of the most moving poems in the collection for me is about a person Bacon was not able to find out much information about, “Shaki Peters, 32, Amite City, LA, July 1.” In this poem, Bacon directly addresses Shaki, “I keep waiting for some story / to explain your murder.” But we know, as does the poet, that no detail will “explain” anything about the hateful violence of these murders. The poem shifts from Shaki to Bacon, the lyric voice conversational and open to what it can and cannot know about the murdered Shaki Peters: “I used to go to a drag bar in Philly” the poet explains to Shaki, where she discovers a trans woman, “sweet, nourishing, a kind / of femme that makes my heart ache” (40). This sensibility of connection with those who died in 2020 stays with us long after we’ve read the poems, studied Bacon’s extensive and respectful notes that document her process and sources, and closed the book.

Transitory by Sughaga Crystal Bacon

BOA Editions, Ltd., 2023, $17 [paper]

ISBN: 9781950774968

Julia Lisella is the author of several poetry collections: Love Song, Hiroshima, Terrain, Always, and Our Lively Kingdom, forthcoming from Bordighera Press. She teaches English at Regis College and co-curates the Italian American Writers Association Literary Reading series.