Review by Sharon Tracey

Review by Sharon Tracey

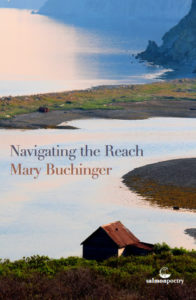

In Navigating the Reach, Mary Buchinger’s fourth full-length poetry collection, the poet wrestles with the slow grief and disorientation of losing a parent and one’s place in the world and how to make meaning of loss. She aptly sums up the challenge, titling one poem “Dying takes every day” and “asks everything” (17)

Buchinger’s poems unspool in lovely narrative lines across time as she triangulates the self with distant points—the home where she grew up in Michigan, her garden back East, an offshore island in Maine. Each a touchstone, a place to weave a cloth out of the contrails of family life and memory, a gossamer net. She often chooses an aerial view from which to make meaning and remember. She finds signs everywhere—a hawk’s shriek ricochets, a hawthorn speaks, a river goes numb, trees don’t stop teaching even as they reach. Buchinger is a keen observer of the natural world and the specificity of her observations and vivid language enliven the poems: “scat of alabaster shells purpled with urchin…airy catkins…hemlock litter…grey knackered twists of uprooted trees.” (78,79)

The book is arranged in six sections and punctuated with a sampling of dementia diary poems numbered and arranged out of order (including enough of them so we can imagine the weight of all the others). In “Dementia Diary #14” she writes of the gusty wind blowing in cross currents, “The snow is confused my father says,/(beat) sometimes we are too.” She goes on, “Where better to look for the self/than in that snow, wind’s prey,” And it’s this phrase—wind’s prey—that moves like a shadow through the poems, staying close to grief like a tease or twist of fate. The most moving of these include snippets of conversations between father and daughter as they talk past one another, bringing the reader inside the experience not by explicating, but by allowing entry into the room inside a conversation.

Buchinger also uses form to good effect, both in shape and minimal punctuation in some poems, as in “Catastrophe” (55). Columnar and justified with just a few dashes and question marks, the gaps between words here and there give the poem an airiness and forward rush (that wind again). The form also evokes a kind of tickertape, a scroll of time, parsed then poured like light through a window pane: (56)

you will never

know what seed fell from your

boot what did you carry how to

catch on to the change before its

wake of disaster….

What o

what does the soft grey rabbit

know carried high up in a clutch

of claw?

The poem “Killdeer” runs like a spine close to the center of the book, born in the Michigan woods

of generations—Native Americans, homesteaders, her own family tree and childhood days, season by growing season, the edges of grief rubbing like a turnstone on grain.

“Flocks of glaucous seagulls/from Saginaw Bay followed like chaos/close behind swooping down” as she and her father ride the John Deere across the flat fields churning the earth and encountering the nest of a killdeer: (40,41)

her awkward dance wing held

out from her small body

that pod of hollow bones

kill-deer! kill-deer! she cried

…My father would stake the nest

with a white handkerchief flag

and the spring planting would obey—

a zig of the drill that dropped the seeds

left a comma in the summer-fat field

long after the fledglings had flown away

The title poem, “Navigating the Reach” near the end of the collection earns its place, moving from the personal to a universal plain. On a remote island off the coast of Maine, the poet walks along the slippery rocks taking note of all she can—black algae, shrimp, hermit crab, racoon, lichen, buoy—and “how much we can’t forsee”, wondering:

if one could tug each

end and straighten

that snaking rope

of intricate seaboard

where land rises and kneels

like memory meeting its grave

and where sea finds

meaning in its own absence

how very long that shore

would be—

And the metaphor of reach feels just right—that strip of rock connecting two islands, visible at low tide but lost to view at high tide—where what we can’t see is taken on faith. Mary Buchinger has created a moving body of poems that hold both memory and grief, never lost but caught in currents tethered to the natural world.

Navigating the Reach by Mary Buchinger

Salmon Poetry, 2023, 14.95 [paper]

ISBN: 9781915022349

Sharon Tracey is the author of Land Marks (Shanti Arts 2022), Chroma: Five Centuries of Women Artists (Shanti Arts), and What I Remember Most is Everything (All Caps Publishing). Her work has appeared in in Radar Poetry, Crab Creek Review, Terrain.org, Lily Poetry Review, and The Ekphrastic Review. She previously served as a director of research communications and environmental initiatives at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.