Barbara Henning

Selections from Girlfriend

Girlfriend is a collection of poetic prose short-shorts about my relationships with girl and women friends from childhood through my present elder years. When I showed my esteemed yoga teacher Genny Kapuler what I had written about her, she said, “I feel honored to be one of the beads in the Mala, one of your sisters.” I like to think about it like that, as a meditation, as a string of beads. Included are friends, family, teachers, mentors and certain women authors and characters who were meaningful to me at important moments and turning points in my life. The writing wavers between poem and prose, like a collage of consciousness, I think, following the way my remembering mind intersects with my poetics.

Linda & Barb

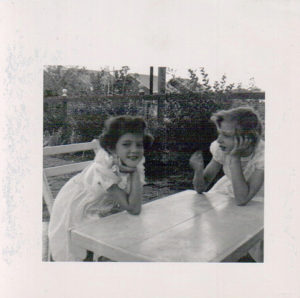

Two infants in the arms of two sisters. Two little girls at a big dining room table writing notes in a secret language. The streetcar rumbles past. Ooday ouyay havay aay igarettescay? Grandma smells a match. Under the covers we hide from the one we love most. Eight years old and hitchhiking on Alter Road. She pulls us back inside. We are only playing, we insist. She gives us what we never had at home—orange juice and blueberry muffins. Ten, eleven, twelve, we meet in the mall, and on the street, I admire your performance of all the swear words in one long stream. ‘67, you are the bride. I am the maid of honor. Hair in a bouffant. Hair in a French twist. Lace and violets. Your garter, my garter. Your marriage. My rebel. Your drunk sailor, my sashaying pool shark. Your little girl, my little girl. The suburbs, the city, office work, teacher work. Many miles between us, but today you stretch out on my daybed, knitting little secret patterns, so adept with those needles, the scarf flowing over the edge of the bed and onto the floor. You look up at me writing in my notebook—“You and Bobby,” you say, “could always read so fast.”

Left: Linda Bakke and Barbara, 1954;. Right: Linda and Barbara, 1967.

Marilyn Meyer

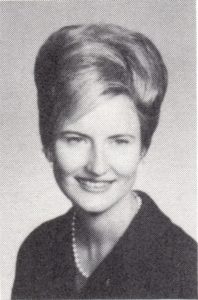

One day you gave our tenth grade English class at East Detroit High School a different kind of assignment. No other teacher had ever asked me to write a poem. We didn’t read much poetry in school. There was one collection of poems in our house. I read all of those. I read the Reader’s Digest books and most of the Mark Twain books that my great grandfather had left me, as well as most of the fiction in the school library. One day, you taught us how to write haiku, and the day after I brought my poem to class; you read it out loud and praised it as an excellent example. I never before felt recognized in school. Then you suggested I join the yearbook staff. I remember I wrote something about a falling leaf. In autumn, I used to lie under the maple tree in our yard and watch the leaves fall. Maybe if I meditate on you and the tree, and write one now, it will be the same haiku, even though 59 years have passed. I sit in padmasana, close my eyes until I’m calm. Then I come to the computer and write,

just a gentle breeze

and the maple leaf breaks loose

falling . . . fleeing . . . gone

Probably it was something like this. Something simple. Something indicating “gone” since I had not seen my mother for four years. Then “fleeing” because I counted the days until I could leave home. Eventually I did leave, and I became a poet, but I wrote my first poem in your class.

MARILYN MEYER. Grosse Pointe Farms, Mich., B.A. DePauw University; M.A. Wayne State University. English; East Detroit High School Yearbook, 1966.

Harriette Hartigan

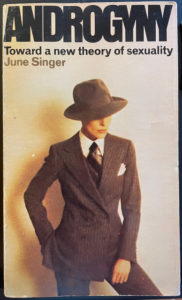

The day after the fire at Joni’s, we both came to help her move, you with your van and me with our old car and trailer. I was eight months pregnant, and you asked if you could photograph me. Some hilarious photos of me nine months pregnant, naked, like a pregnant witch, flying around the room on a broom. Then a difficult home birth. After two days of labor, we all went to the doctor’s office in your van. Your water will break very soon, she said, so we hustled back home for a baby, my little girl, and you were there with your long hair, long legs, cowboy boots, and your 4 x 5 documenting every moment. You became a midwife photographer, and our families became close, so close that we became lovers for a short time, then friends who were once lovers. “Androgyny” was the word of our time, and we lived it. Once my toddler daughter pointed at a photograph on a Women’s Studies textbook of a slim women wearing a man’s suit, and she called out your name, “That’s Harriette!” You were ten years older than me, the mother of three boys and several others who needed you. I loved the way you brought bits and pieces of the natural world into your house, into your photos. When I was living in Tucson, I sent you a devil’s claw and you were ecstatic. Always struck by the messy wild world, its beauty, the excitement so much sometimes that you needed to calm down, chill out with a bottle of wine. One became two and for a long time, I didn’t pick up the phone at night. In your late 70s, overnight you quit drinking and moved in with your son in Arizona on a ranch, near the border of Mexico. Even though the middle range of your eyesight is challenged, you still wake up in awe of the world, surrounded now by animals and desert plants.

Left: Harriette Hartigan and Barbara, Nov 17, 1975, Photo by Allen Saperstein. Middle: Harriette, 1980, photo by Barbara. Right: Androgyny: Toward a New Theory of Sexuality, by June Singer.

Maureen Owen

In ’88 Lewis asked you to write a blurb for my first book, Smoking in the Twilight Bar, and you did. Over the years, we hung out now and again at poetry readings in NYC, Tucson or in Boulder. We taught together for the online program at Naropa, and we talked on the phone many times. The year before the pandemic, in our seventies, with grown children, and grandchildren, we circled the country on a reading tour. I taught you yoga, and even though I try to be optimistic, I had to keep up with you, especially in Albuquerque when my lungs didn’t like the altitude, the cold air and the dirty hostel where we were staying. I couldn’t breathe, so you helped me carry things upstairs. You could stay up all night talking about poetry. Once we sat in the Walmart parking lot, making tempeh-tuna sandwiches on a cutting board, and we laughed at ourselves. Problems? Sure. Someone was always in a hurry, someone was irritable, someone was snoring, someone forgot to take a photo, someone said something to hurt the other, someone needed to be alone, someone was cold and there weren’t enough blankets, someone was worried about what was going on at home. But look at that mountain, that cloud formation, the wind turbines, those poor cows corralled like that, clink clunk, someone’s shoulder caught in a cramp, a sticky shift, someone wants to eat real food, someone wants to kill the bully, but someone is a pacifist, someone needs to write alone, someone needs to be alone. Now I call you up when I can’t think of the right word. I say that all my relatives died around my age, and you advise, that’s not the way to think about it, Barb. I had trouble sleeping, but you could fall asleep anywhere. Two months in a car and fifteen poetry readings later, at the end of the trip, I was camping out in the room in your basement. When I went upstairs to ask you a question, you were in a U shape on the sofa, sound asleep. Another time, you were leaning on your mother as she gazed out the window, sound asleep. What a gift, to be able to sleep like that.

Maureen Owen and Barbara, 2007, Mission San Xavier del Bac Cemetery. Photo by Laynie Brown.

Diane di Prima

I arrived in the East Village fifteen years behind you and your friends. In the early ‘70s, in Detroit’s Cass Corridor, we were also inventing our lives with as much personal and artistic freedom as possible. Not just the men. Us, too, with our strollers. A thread, a continuity. After I wrote you asking for poems in Long News, for many years our postcards, books and letters went back and forth. Always encouraging, you wrote, “I take you your friendship your work seriously and want always to give you full attention. Love you. Diane di P.” By October 2010, your health had taken a downturn, and you were carrying an oxygen tank when you came to NY to read. I introduced you and Judith Malina at the Living Theater. On my shelf, a very ethereal looking photo of you and me taken in the dark. When Maureen Owen and I stopped to see you in the nursing home, you cautioned us because there was a flu that month. The year before covid, we weren’t concerned. On the altar in your room Buddha, Trungpa, a Poetry Project newsletter, a windmill and a few spiritual books. In the photo, a mirror behind the altar, my image looks back with the camera. You couldn’t move your legs. I sent you a bottle of mahanarayana healing oil. I wanted to help, but by then not possible. Bedridden, still you laughed and talked about your new book, Spring and Autumn Annals–each paragraph a poem, revealing the joys, trauma and losses of living artistically on the edge with children. A poem, a history, a map of a place, time and people. Dedicated to your dear friend, Freddie Herko. “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” You loved Keats. Much truth here, much to give. From Hunter College to Poet Laureate of San Francisco. All for beauty, truth, and love, big love.

Left: Diane di Prima and Barbara at The Living Theater , Oct 20, 2010, photo by Dumisani Kambi Shamba. Right: Diane and Barbara, 2019, Jewish Home for the Aged in San Francisco, photo by Maureen Owen.

“Diane di Prima” was previously published in Juleboard, Issue 2, Sept/Oct 2023.

BARBARA HENNING is the author of five novels and eight collections of poetry, most recently a hybrid biography of her mother’s life, Ferne, a Detroit Story (2023 Library of Michigan Notable Book; Spuyten Duyvil Press); Poets on the Road (with Maureen Owen, City Point Press, 2023); a novel, Just Like That (SD 2018); and a poetry collection, Digigram (United Artist Books, 2020). In the 90s, Henning was the editor and publisher of Long News: In the Short Century; she is also the editor of Looking Up Harryette Mullen, The Selected Prose of Bobbie Louise Hawkins, as well as editor and author of Prompt Book: Experiments for Writing Poetry and Fiction. She has taught for Naropa University and Long Island University where she is Professor Emerita. Born in Detroit, she presently lives in Brooklyn. Readings are on Penn Sound. www.barbarahenning.com

BARBARA HENNING is the author of five novels and eight collections of poetry, most recently a hybrid biography of her mother’s life, Ferne, a Detroit Story (2023 Library of Michigan Notable Book; Spuyten Duyvil Press); Poets on the Road (with Maureen Owen, City Point Press, 2023); a novel, Just Like That (SD 2018); and a poetry collection, Digigram (United Artist Books, 2020). In the 90s, Henning was the editor and publisher of Long News: In the Short Century; she is also the editor of Looking Up Harryette Mullen, The Selected Prose of Bobbie Louise Hawkins, as well as editor and author of Prompt Book: Experiments for Writing Poetry and Fiction. She has taught for Naropa University and Long Island University where she is Professor Emerita. Born in Detroit, she presently lives in Brooklyn. Readings are on Penn Sound. www.barbarahenning.com

Barbara Henning Photo by Mook Saperstein