Review by Jiwon Choi

Review by Jiwon Choi

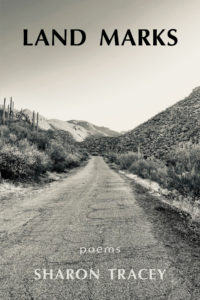

In Land Marks, Sharon Tracey’s third book of poetry, the poet has created a body of work that evokes what Robin Wall Kimmerer describes as the longing to live in a world made of gifts, for “we have grown weary of the sour taste in [our]mouths”––the sour that comes from being obsessed with the economy of commodity. And though you will find commodity in Land Marks, you will find them in Tracey’s astute taxonomy of flora and fauna: California quail and gray fox after a wildfire; North Atlantic Right Whale about to be autopsied; Saguaros that provide haven to the elf owls.

Tracey is doing the heavy lift of trying to bring us to a fundamental understanding: being on this earth means being connected to everything in it. And she manages this task with methodical pleasure and focus when she bids us in “To All the Starlings,” to be “open and aware of all the others.” And by “all” she means it!: horses, cetaceans and crustaceans, chickens, pigs, wildcats, ants, “the last red wolf.”

Come one, come all.

One might be tempted to consider many of the poems in this collection as meditations: “If existence is the exchange is the music/is the water flowing down the light it catches.” But more precisely, feel them as a tap on the shoulder, while the poet whispers in your ear, “Look up, look down, look fully around to see how interconnected we are.” Just like the starlings “exchanging feathers as if one organism,” summoning the feathers of Mary Oliver’s “Clapp’s Pond”:

flowing together until the sense of distance ––

…………………………………………………….

vanishes, edges slide together

like feathers of a wing, everything

touches everything.

The natural world is a major protagonist in Land Marks, but Tracey has not forgotten the man-made world, with its edges sliding into the natural one. In the apt homage, “After Hopkins,” welcome the ritual of seeing brilliance in the mundane: the “dappled light on the stream of cars stopping for gas” and the “Liberty Tax man dancing curbside in his mint green costume.” Discoveries that feel like a palate cleanser of sorts. Ah, here is a remedy for that sour taste in our mouths.

But no one book can erase all the sour and that is okay. What we’re really seeking is what Kimmerer wants when she writes of a yearning to understand the “architecture of relationships, of connections…the shimmering threads that hold it all together.”

Turn to page 67 of Land Marks and you will find one of these shimmering threads in “What the Poverty Grass Said on Route 66”:

if you are homeless come

if you have humble hands come

if you have rambling hopes come

pick me gather me up

make a mattress tick to rest

your bones.

Yes, I hear it too, Emma Lazarus’s creed inscribed on our Lady Liberty in the New York Harbor:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Land Marks is truly a world made of gifts, here are poems that give us time and space to rejoice the beauty and agonize the cruelty of the world as we experience it. Early on, in “Prairie Dropseed and Me,” Tracey confesses that she wants to “believe in beginnings and endings,” stopping short because she knows the world will keep “recycling.”

But as I read these poems in what is being recorded as the hottest month on Earth and wildfires rage through Maui, I do believe in endings. As must the pilgrim “carrying a six-foot white cross on his right shoulder” in “Driving up Haleakalā, House of the Sun”:

…he trudges uphill to the point

where earth, sea, and sky

form a perfect trinity.

And though I will mourn the ineludible demise of our human species, I am doubly aggrieved to know that we will lose the creatures, great and small, Tracey has cataloged here with such attention and care. Some fare better than others in our practice of putting living things in a hierarchy: bluefish become dinner and the horseshoe crab marauded for vaccine research.

But some have found their well-earned place under the poet’s watch, even in death.

How lovingly the bird of “least concern” in “One Hairy Woodpecker” is laid to rest:

with a handful of summer

buttercups.

Scan a few dead trees for kin

who might sing for him.

And if anyone asks, “Which are the creatures of most concern?” We must all answer, with a copy of Land Marks in hand, “All of us.”

Land Marks by Sharon Tracey

Shanti Arts Publishing, 2022, $15.95 Paper

ISBN 9781956056624

Jiwon Choi is a poet, teacher, and urban gardener. She is the author of One Daughter is Worth Ten Sons and I Used To Be Korean, both published by Hanging Loose Press. She started her garden’s poetry reading series, “Poets Read in the Garden,” to support local poets with live readings events. You can find out more about her at iusedtobekorean.com.