Review by Ruth Hoberman

Review by Ruth Hoberman

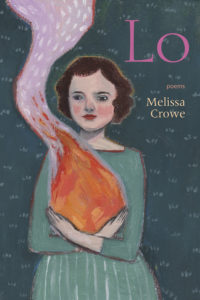

Melissa Crowe’s Lo (her second collection of poems) is compelling, even suspenseful. Each poem pulls us farther—irresistibly—into the speaker’s rural childhood, through the trauma of molestation, and into the complexities of adulthood. I followed eagerly, utterly absorbed. Why? Two things occur to me. First, the poems capture a feeling I suspect we all share of being haunted—by different ghosts perhaps, but surely we all have some hovering regret, horror, or fear we’d love to expel. And second, through their lush details and direct address, the poems invite the reader so emphatically in.

As the title indicates, the book is very much addressed to us (look, the word “lo” tells us: something surprising has happened). Many poems mention a “you” (sometimes the speaker’s husband, sometimes not); others command us to get involved. “Say I’m clover and Queen Anne’s/lace, devil’s paintbrush and lupine,” the first poem begins, inviting us to join the speaker in making metaphors as she tries to locate her voice. These metaphors are so concrete, so easy to visualize —“I’m a yard of junked cars, each/with its corona of broken glass”—that we happily follow them into the surreal: “I pull/a wagonload of hearts to the store/at the end of my road, trade them/for dimes, and say the dimes/become my heart.” Surreal, but also a vivid depiction of rural poverty knee-deep in wildflowers—a landscape familiar to Crowe from her childhood in Presque Isle, Maine.

This landscape, with its broken glass amid the clover, haunts Crowe’s poems. In the book’s title poem, “Lo,” the speaker attends Bible camp, where “lo, there were bibles, free,” but she can’t afford horseback riding lessons. Instead she offers herself to be saved: “to be lifted from my life by some/animal bigger than me. Possessed of lungs, wet eyes, silken/flanks, I burn. Lowing, lo—feet in sawdust, head upturned.”

That burning recurs throughout the book, most notably in its third section, “When She Speaks of Fire,” a powerful sequence in which what resonates is the silence surrounding a memory of molestation that can’t be articulated for fear of combusting:

. . . Let my

parents find out, don’t let my parents

find out about the man, the man’s hands.

And having heard them joke about spontaneous

combustion I prayed, Dear Jesus, don’t let

that sudden fire burn in me.

This section feels different from the others—less narrative, the stanza forms more varied—evoking the disruption wrought by trauma. But here, too, the poems reach out beyond the speaker’s “I”: “maybe you’ve been trapped these/long years, too. Of course, any house can be/a closet, the mind can be a closet, and some/basement-nautilus-jacked arm, some world-/harmed, harming clown still bars the door.” In fact, the man who will become her husband is also “screaming, too, from a closet…He’s out here now/with me, we’re both alive. We touch.”

The book’s final three sections release us into (mainly) happier times: a husband, a daughter. One of my favorites, the incantatory “Epithalamium with Inventory,” celebrates marriage (as the title “epithalamium” indicates) but also survival (“I climbed out./You climbed out”):

…Days

like smoke or like cool ether we breathed

and breathed through, and what do I have

now? O moon, o day, window, river,

blood, o bird, o hand, o fist, o world—

you. And will you have me, too?

Danger hovers—in the “truck-mad” highways, shootings, drug-abuse, illness, and (in the final section) pandemic and Trump-era cruelties. But throughout, Crowe’s poems exhibit a kind of tenderness toward things—whether in the past (like the remembered “white cotton/leggings with the delicate cuff of lace at each ankle”) or, in “Benediction with Foundlings,” unfolding in the present moment: “May the next squirrel kit who falls/from tulip poplar to leaf bed curl into the kin-/pink of my palm.”

The speaker’s openness to the world is echoed by the book itself, which opens outward, broadening its scope: “What a world we lot have made by hand,” the speaker exclaims, as she explores human cruelty—which is sometimes necessary (a friend kills a rattlesnake) but often random. Love of beauty and family is haunted always by fear of loss. We see rabbits by a busy highway, she writes, and feel delight in “their soft wildness, then dread.” As a country and world, we haven’t done nearly enough to protect nature—or people—from ourselves. “America,/darling,” Crowe writes in “America You’re Breaking,” a poem of deep if broken-hearted affection: “America, I was/a stranger and you teargassed me?”

“I’m trying to forgive you,” Crowe writes at the end of the book’s final poem. “And if you’re/wondering who you are, you’re everyone.”

Lo by Melissa Crowe

University of Iowa Press. 2022 $20.00 [paper]

ISBN: 9781609388997

Ruth Hoberman