Review by Kimberly Ann Priest

Review by Kimberly Ann Priest

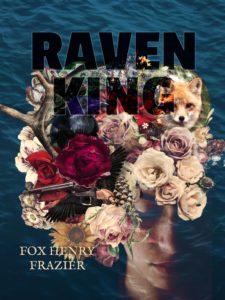

Flee Evil

“Is the significant difference,” asks Fox Henry Frazier in Raven King, “between a man like Cas and a man like Charlie simply that Charlie chose to run away from his violent potential, rather than towards it?” (pg. 153). Frazier’s mausoleum of poems in Raven King, largely dedicated to the ghosts of harmed women past, is crowned by this question in the book’s final literary offering, an essay titled “I Live in the Shadow Hills.”

Indeed, Raven King is a book of shadows, and the question is appropriately posed to underpin the speaker’s search for reason amid violent chaos. In these pages, female victims, like those of the Manson murders, or Maddy Lerner and Hazel Drew in upstate New York, among many, many other molested, battered, and /or murdered women are accompanied by Diane Arbus, a twentieth-century American photographer who reveled in befriending and photographing marginalized persons in familiar settings; Countess Elizabeth Báthory de Ecsed, the accused Hungarian serial killer of the fourteenth and fifteenth century; and members of the Catholic Worker’s Movement in Ithaca, New York who bathed a Military Recruitment Center in their own blood to protest the USA’s invasion of Iraq in 2003. All these women are accumulated to accompany the speaker, a Fox-Haired Seer, on her journey toward realizing the vulnerability of women in a male-dominated world alongside a search for what will protect them. However, no matter what a woman does, the Seer seems to lament, this vulnerability is inescapable and affects us all.

For the Seer, entanglement with male violence is personal. She is, as many women are, victim to predation and battering herself. A man named Cas becomes her sweetheart and husband, hiding a history of violence she later discovers in police reports accessed during her divorce proceedings. Evidence of bar brawls and broken limbs force her to reckon with the intimidation, threats, and physical violence her husband has enacted during their marriage. In one of the many “Exodus in X Minor,” after finding evidence of infidelity she writes:

A spouse transforms into

something else after he fucks other women, but

still something else after he threatens to kill you.

A spouse becomes something

else after he works

up the nerve to mean it. (92)

Like many women, these discoveries come too late, after the scars and consequences have already begun to take their permanent toll. “I expelled luminescent / pearls from my heart valves to his feet,” she writes in another Exodus poem,

his hands closed around my

throat my chest seizing to breathe

Spirits gathered like locusts I unfurled

my wings and screamed bled

from my mouth tawny burnished … (108)

A dreamlike sequence weaving through personal narrative and other narratives both present and past, Frazier’s work ponders the dark obsessions of Los Angeles, California and Upstate New York—formative locations in the life of the poet-seer. In upstate New York, a hub for spiritualism, the Fox-Haired Seer speaks to other seers and visits locations of women who have died violently, giving voice to their pain. In “The Fox-Haired Seer Makes a Pilgrimage to Devil’s Elbow, NY, Where in 1923 A Steam-Shovel Operator Discovered the Skull of an Axe-Murdered Young Woman; and Listens,” she allows the woman to speak:

My last moments illuminate

before me like Leda’s

smothered convulsions

against downy breast, the cleaved

immortality that comes

After. (pg. 32-33)

And in “Everywhere in the World, They Hurt Little Girls,” she tells the story of Cheri, a girl who got a paper route in her NY hometown and delivered papers after school to raise money to throw her pregnant middle-school teacher a baby shower. “[B]ut one day,” she writes, it happened that James …

was a week overdue on his subscription, and her mother

had to get dinner started so Cheri went

unescorted to James’ house, which is when James pulled her

right off the front steps and locked her in the house

with him, and hurt her … (pg. 65)

Cheri’s body is found later.

In Los Angeles, the Seer feels and attests to the middle- and upper-class shock when violence is directed at them or includes their ‘kind.’ Speaking of Los Angeles’s fixation on the Manson murders, she writes,

I think that part of our macabre fascination with this particular crime, as embodied by its unholy shrine at the Death Museum in Hollywood, is that people murdered at 10050 Cielo Drive were not only racially and socioeconomically very privileged, but some of them were famous. In popular American imagination, this would have been expected to somehow protect them from such acts of violence. To prevent them from experiencing ultimate helplessness. (139)

But no one, insists the Seer, escapes the possibility of ultimate helplessness. In a world where male violence is itself often protected as a form of social currency, even women are subject to join the program. Her own husband, Cas, “a hard-drinking, thrill-seeking, drug-addled” man in the “blue-collar subculture of a dying industrial town” in upstate New York, “nestled among the intersections of various dearths of opportunity,” makes use of some of the only currency he has to survive—male physical dominance. And in this sort of culture, “the physical dominance expressed by a man in a public setting will be granted socially, by extension, to his female partner (if he has one) for as long as they are romantically linked.” (pg. 136) This is powerful insight.

To let go of that currency, the Seer must absolve herself from seeking its protection and finding other ways to protect herself—an arduous task in its own right. She must, with Elizabeth Báthory in a dream, figuratively bathe in the blood of murdered women; she must learn from Diane Arbus to become comfortable with her shadow-side; like Charlie Manson (not Charles Manson) who left the Manson cult before its adherents became murderers, she must also run from the violent potential of men; she must leave her partner and teach their daughter to be “[shepherd], [sister], to heal the sick, to sew / clothing. To make soup and tea, medicinal tinctures, conjure / courage where none exists” because she comes from women “who don’t fear pain / the way men fear pain.” (The Sunny-Haired Undertaker’s Daughter and the Raven-Haired Cartographer’s Daughter Write Letters Amidst the Pandemic, pg. 122).

She must do what few men choose to do—flee evil.

She must, as she says in “The Raven-Haired Seer Selects a Card from Her Own Handmade Oracle Deck to Symbolize the Querent on Her True Path, and the Image Is the Woman King of Bones and Stars, “[rise]again like origin.” (pg. 116)

Reading Raven King is an immersion I will never forget. An opportunity not to fear the pain of awareness but to see violence for the sick obsession that it is. Nothing in this book is romanticized. Male violence is not a hot topic; it’s a sickness we need to cure in our culture, ending its dalliance with the vulnerable.

Raven King by Fox Henry Frazer

Yes Poetry (January 17, 2022)

Paperback : 192 pages

ISBN-13 : 978-0578995403

Kimberly Ann Priest is the author of Slaughter the One Bird, finalist for the American Best Book Awards, and chapbooks The Optimist Shelters in Place, Parrot Flower, and Still Life. She is an associate poetry editor for Nimrod International Journal of Prose and Poetry and assistant professor at Michigan State University.