Olivia Cronk

excerpt from “Mothering as Archive as Textural Surface”

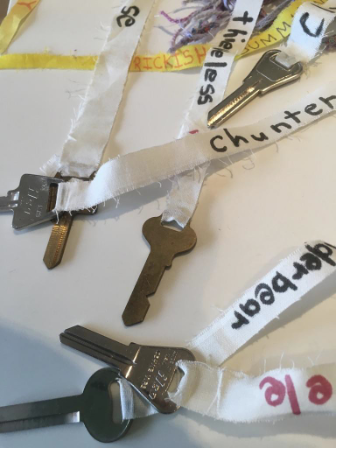

With Visual Art by Anne Zielenski Fleming

A Quipu That Remembers Nothing consisted of [Cecilia Vicuña’s] act of thinking about a quipu—the knotted cord method of communication used by Andean peoples beginning around 3000 BCE . . . there are no material remains . . . of Vicuña’s imagined quipu, aside from her recounting her thought to others and writing about it as a little note after the fact. This “mental thread” stretched from her mouth to this page like an oral history, told first to herself and then retold by others, reknotted as it is rearticulated over time . . . it raises questions . . . about the disappearing archive that resides in . . . shifting memories.

-Julia Bryan-Wilson, in Fray

How does a mother produce a bridge between haptic and visual memory?

How does a mother produce a textural archive?

What is the lore created by the memory’s tether to textural surfaces?

When I say that my mother is a visual artist, I both mean and do not mean to offer an overt critique of the institutionalization of Art; I both offer as evidence her occasional participation in “institutional” Art practices and refuse to say that such activities specifically confer upon her the status of Artist. I reject any hard division between aesthetic domestic labor and institutional celebration of the Artist. When I say that she is not merely a hobbyist, I do not seek to render hobbyists powerless in the thrilling inflections of information that make the living body of Art. I am cognizant of not only her BFA in Textile Arts but also of my entire life of watching her sew, weave, mend, sculpt with fabric, tinker–her acts usually in service of what we might think of as Art-as-daily-living (items for her grade school students and classrooms, items/clothing for me and my brother, costumes, pillowcases, curtains, art objects for the home, and much later, occasional objects for institutional display, though these always as part of some psychological inquiry she was pursuing, and so, in my thinking: a kind of Art-as-daily-living, too).

My mother would simply refuse any/all of this discussion about categories and ethos.

My mother is, I think, always and only after the narcotic experience of Art-making’s task-doing: the planning and executing, the psychedelic fog of thinking it up and using one’s hands to make, out of nothing, a new textural surface.

I imagine that my mother and I would list some of the same events as the most crucial ones in our relationship, but perhaps I’m wrong. There is all the unknown-to-me time of my baby and toddler life.

I presume, though, that we both recall with some tender blend of horror and comfort the weeks in which we slept on single beds next to one another in the bedroom that had been mine in high school. My father had just died. I was eighteen years old. We had the lovely bedroom aesthetics of lower middle-class life in a family that has saved and hoarded useful and pleasing items for decades: faded gaudy late 80s striped sheets and mismatched pillowcases from the 70s; some variety of homemade and department store blankets; dressers from Sears, bought on the cheap in unfinished wood and varnished by my mother’s own hand. Taupe-brown carpeting. The crackling of all this: sleeping inside of death’s pocket: the room a collaged surface on which grief could skate.

I’m interested in how my mother created, both knowingly and unknowingly, an entire world of textural surfaces: walls/panels/screens (both homemade and store-bought textiles, curated, juxtaposed) that slid in and out of eras, surfaces on which we could all have visual-haptic encounters. Perhaps a room of textural surfaces would be more apt.

Mothers as shadowbox-makers.

I remember when my mother showed me the Joseph Cornell boxes at The Art Institute of Chicago.

And I remember when my mother taught me the steps to make a patchwork quilt. I remember watching my mother cut thread with her teeth.

I remember the heart print curtain my mother sewed as a cover for the glass door of the antique secretary she allowed me to move into my room when I was nine.

I remember when my mother took me to an art installation in which we walked through a rectangular space of clear plastic strings hanging from the ceiling, fully available for touching. And though this was one of my most important early, formative experiences with Art and with my mother, when I have asked her about it, she does not recall it. In internet-searching for what we experienced, I find the likely source was Jesús Rafael Soto’s Pénétrables. He had an exhibition in Chicago in 1986, and this fits. I was eight years old. In my memory, in the shimmery room to which I attach this encounter, my mother tells me that we are allowed to walk right into this piece, through it, thus undercutting my previous training in museum-behavior; she disappears in a foggy and un-terrifying way. It’s a room inside of a room.

Images of my mother’s work woven into my writing: an archive: a lulled snapshot on the continuum of domestic textural surfaces, a conversational practice with my mother and in which I’ve been participating my whole life.

The day or two after my husband and I brought our newborn daughter home from the hospital, my mother came, in classic women’s-network-of-care tradition, to sit the day with me and the baby. I think I had some minor writing work to do. My mother was sewing something and set up her sewing machine on our grimy kitchen table. We put my daughter in a bouncy chair and made a tiny digital video of her. We drank coffee. In the video, my mother’s voice says, “That’s cute”–and I don’t know if she’s describing the whole effect (my daughter’s little newborn clothes and her funny clenched fist and thoughtful expression and the silly hand-me-down baby chair with its outdated safari print) or a specific gesture or particle of mine or hers. We three are all eerily jumbled here, though the vibrating panel of the video and its colors certainly center my daughter’s presence: a new person with whom to animate with our textures: though neither adult can be seen, we two women crowd into the peering at this small shimmering creature: we’re at the edge of the canvas.

In a different piece of writing, I tried to describe the morning that my mother and I went to the bank immediately after my father died–her desire was simply to keep the accounts available before his death became a tangle of paperwork, so we did not explain why she needed to change the name on the account to mine. We were sleep deprived, in shock, wired. The woman at the bank knew something was strange, but there was no reason to pry. It did feel a bit like a crime, though it was not. And though this was not my first time living in the nauseating music-box world of the days following a death, it was my first time doing so after the death of a parent. My mother was steady and clear. Sign the forms. Task-doing as care after a trauma is perhaps the most consistent trait of my mother’s ways. I wrote about this, twenty years later: “an erased distance instantly produces a kind of archive.” I don’t know what I meant except that I wanted to explore the feeling of deep dissociation as a shared encounter; we were in a texture, swimming in textile, atop a visual-haptic experience, together. Later in this same piece of writing, I tried to describe the link between learning to breastfeed a screaming and angry baby (my mother next to me) and an incident when I was twelve: my first or second time trying to insert a tampon, my mother waiting outside the bathroom door so as to make herself useful, our quickly disappearing plans to go lap swimming together, my utter rage at my body and the impossible-to-use cotton plug that stood between me and life. I described the bathroom door as a skin-sea. I felt the skin-sea rise up again with my daughter’s mouth on my inept nipple. My mother, attentive to task-doing and solutions, practical, empathetic without sap. The archive of all this.

These events remain, for me, a kind of lore, a way of being inside of my own memory, of turning my eyes inside of me where I can find my mother and myself at the bank desk or at the skin-sea.

How does a mother produce a bridge between haptic memory and visual? How does a mother produce a textural archive?

One night my daughter and I are reading a book, and I am performing the text and in doing so modeling for my daughter what awareness of syntactical rhythm can do for textuality, and how when we read aloud, we can create these textural rooms (or panels?) of sound and meaning and narration and aesthetics and memory. And she says, “Did you see that the window is open?” And I am annoyed to be interrupted and we are sitting nowhere near an open window–though the mirror in our bedroom is next to us and for a moment I think she’s gotten into one of her psychedelic moods–and I say no. Then, like stretching a mental thread and somehow making it have material reality, like I am dreaming or stoned and drone music is coaxing a piece of embroidery floss out of its stitch and into a drip, she moves her finger into the book and onto the page: right here. There is a sketch inside of the book, and a curtain blows wildly in the space of the open window.

A thing Julia Bryan-Wilson says about Cecilia Vicuña’s piece “The Glove”–which takes place on a public bus: she binds her hands to the bus’ meter and front railings, purple and pink threads twisting around, the front window view of the bus hanging over the bound hands like a kind of vibrating forecast–the “weaving of gazes.”

How visual and haptic experience come to be a set of tunnels pushing us around our experiences of history. And how textiles, as textures, create those little hamster paths for us. My mother and I looking in on my daughter in the video panel, weaving our gazes around her as a way to structure.

All this weaving and haptic gazing and my mother’s hands laying out the paneled rooms that leave open the invitation for the pulled thread. And then the disappeared and disappearing archive.

Preparing for this essay, I am shocked one day to realize that if I want to make claims about my mother’s work (here, again, I won’t distinguish between her housework and her “Art” but rather: I will note that they are one body that wrapped itself around my tunnels) as surfaces for encounter, as panels, as rooms . . . then I must also note that perhaps Writing is the same work. And the tidiness of saying that my mother’s weaving and sewing are a way of writing is narcotic.

An oft quoted but apt thing that Vicuña says: “When a girl is born, her mother puts a spider in her hand, to teach her to weave.”

Dream-state control over the surface.

So few ways, anyway, for an individual to claim agency. Might as well weave-write-sew our own tunnels.

A kind of fairytale: my mother gave me two giant panels of oilcloth, cut to fit the dining room table my husband and I inherited from my stepfather when we moved into the second-floor apartment of my grandmother’s two-flat. The prints on them are lovely and garish. As I type this, I sit at the table’s oilcloth surface and look out to the red curtains I sewed after a trip with my mother and daughter to a fabric store. My mother found the bolt of fabric and thrust it into my gaze.

Wondering about thinking as touching: if my mother “wrote” the textural/textile-based panels and rooms of my early life, and if I was doing my own early form of Art-making’s task-doing by thinking across and inside of them, and if her own gaze was both structuring and weaving with my own, then . . . she was thinking this very essay into a surface.

If my mother treats task-doing as care, and if she’s deep into the pleasures of Art-making’s task-doing, then what do I know about the relationship between Art-making and care? Or: what do I know about my mother’s free time? Or: what do I know about staying busy in the soft apocalypse? Or: are mothers’ aesthetic tasks a kind of Conceptual Art that serves a dual purpose: infect the child with texture, care for the child . . . ?

Another fairytale: my mother emails me images of her work to weave with my writing. They proliferate like postcards from a secret room.

She sends me notes about her thinking about medium, and in particular her love of unexpected juxtaposition. She is interested in what it means to constantly churn together metal and fabric.

Another email from my mother, this one a transmission from fugue-y history space:

liv,

you might want to use this in your piece. I don’t know if me or daddy ever told you but he got all those cool rusty things from what was landfill when he worked in printers row . . . leftovers from the old “levee district” which was where everything was happening in old chicago . . . that stuff is not only visually neat it’s also historically quite poetic

And as I copy the email’s surface into this other screen’s surface, I remember not remembering this, or I don’t remember remembering this, or, I’ve re-written, re-woven.

I touch-think about this archive: the constantly re-usable, rewrite-able material of Art-making’s task-doing: an eternally stochastic surface, glitching its way through our gazes and infecting our loved ones’ haptic tunnels.

Anne Zielenski Fleming is a textile artist and retired public school teacher. She lives in Chicago, IL.

Olivia Cronk is the author of WOMONSTER (Tarpaulin Sky, 2020), Louise and Louise and Louise (The Lettered Streets Press, 2016), and Skin Horse (Action Books, 2012). She lives in Chicago, IL.