Review by Anna Laura Reeve

Review by Anna Laura Reeve

Kirsten Shu-ying Chen’s impressive debut centers her experience caring for her dying mother, and the established structures and systems that erode under the influence of that grief. These poems exist in a liminal space, functioning both as the small light of human perception glowing in a universe of dark matter and as an eye, pupil dilating and constricting, as the light changes. It’s a kind of through-the-looking-glass guide to life after such a life-altering loss, a dotted line tracing the journey from the certainties of the beforelife to an acceptance of paradox, which is—Chen makes clear—as rich as it is difficult. Chen’s images and rhythms are lucid enough to take any reader inside her experience of loss and make that space suddenly strange, unspeakable and unreal, deconstructed and pixelated, and then as real as skin on skin.

Chen’s voice is immediate, solid, and clear, and takes the reader on a journey that feels both cyclic and linear (though linearity is challenged throughout the collection), spiraling outward from tender, heartbreaking poems to poems frozen in a limbo of thought, considering grief and loss from every available angle. Initially, the five sections of the book—”first light,” “set light,” “black light,” “bounce light,” and “ultraviolet”—reminded me of the canonical hours of the Catholic church, a daily cycle of set prayers beginning before dawn and continuing through the night. These prayers set a compelling rhythm for the life of the believer, persistently calling attention to the angle of the sun, or the quality of star light, and light wave’s sequencing of poems creates a companion image to the believer who prays for illumination: a speaker, illuminated by the shifting light of grief, which is “a closed circle, / concentric in its company, and radiating / like the fire does” (7).

Many poems early in the collection are free verse, orderly short lines in columns or stanzas, which belie their sense of unraveling domestic orderliness. Some are set in the house where the speaker and her father are caring for the dying mother, and here, what I call the ‘eerie domestic’ comes through powerfully, as the house and domestic tasks—formerly a source of comfort or security—take on strange shadows, are sucked clean of their old character, as the family within it changes roles, habits, and function. I loved these claustrophobic lines from “Large Nude in a Red Armchair”: “I hold a paranoia for household spills. / I have an ear for certain silences.” (13) And these lines from “Hubble Deep Field,” pointing at the unknowable that hides behind our certainties:

We suppose there is logic.

We suppose there is something

definitely.

Attaching syllables

to fire, we suppose.” (21)

Chen’s lyric sensibility is beautiful, subtle, and restrained, even as poems later in the collection gain more white space, with lines indented and aerated and set loose to drift across the page. The format of these poems reflects their liminal function, as the speaker catches a firmer hold of what the loss of her mother means: “I miss true north” (50).

The final poem in the collection, “The Closest We Get to Freedom,” seems to conclude, in its reflection on “five-dollar bodega flowers” that are still alive “an entire month later,” that the freedom that exists within family and domestic life is harrowing—we are so free of each other that we can, and do, leave each other—and that our choice to persevere, even bloom, are acts of unique power. It’s tough not to compare this collection to some of the work of Ocean Vuong, whose sensitive renderings of his own mother’s suffering and separateness, and his grief for the absent and impossible in their relationship, created so many beautiful lines. But Chen’s mother, despite sharing few physical or cultural similarities, appears in these poems as less an unreachable muse, and more an object of enormous affection. That affection, which had been anchoring, billows out like unsecured sail, snaps and frays. Tenderness, choosing to bloom, in such a world—Chen shows us how it is done, and what it costs. A gorgeous and insightful book.

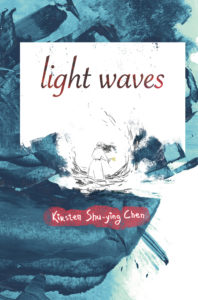

light waves by Kirsten Shu-ying Chen

Terrapin Books, 2022, paperback

ISBN 9781947896550

Anna Laura Reeve is a poet living and gardening near the Tennessee Overhill region, historic land of the Eastern Cherokee. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Beloit Poetry Journal, Rust + Moth, Terrain.org, and others. Her first collection, Reaching the Shore of the Sea of Fertility, is coming in 2023 from Belle Point Press.