Review by Emily Webber

Review by Emily Webber

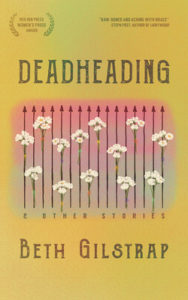

Deadheading & Other Stories, Beth Gilstrap’s short story collection, portrays women in the Carolinas as they endure hardship and process trauma, and explores our connection with the natural world and family. Gilstrap’s flash fiction has appeared in literary journals such as Wigleaf, Jellyfish Review, Ninth Letter, as well as the Best Microfiction Anthology. She creates stories lush with details and sensations, even in short spaces. She showcases these skills in the flash fiction and longer works that make up this collection.

Place is not merely a backdrop in these stories; it is in the bones of these characters. Family is another central theme—what is passed to us in our DNA, how we actively long for and preserve our family traditions, and how we try to escape.

In “Like Air, Or Bread, Or Hard Apple Candy,” a woman walks her dog at night and notices how the neighborhood she has lived in all her life is changing. Her great uncle’s property is being demolished.

Grenada takes a big breath, the microscopic debris catching the rustle of autumn wind, leaves dry and brittle and caramel sweet, and wonders if she’s taking in the last physical remnants of her long-dead relatives, a fragment of hair, a skin cell, some crumb of biscuit hidden under the fridge, never gathered, never cleaned, never consumed until now. (89)

In “Sinking and Swaddled,” people will not leave their houses and are consumed into the earth. Both stories unpack the impact of gentrification and our connection to our history, family, traditions, and what happens when we are absent from each other and the places we are connected to emotionally and physically.

These stories will leave marks on you. When I read the second story in the collection, I had to take a pause. The last line gutted me. It made me think of my son, who has many advantages, the opposite of the boy in the story. There’s an unfairness of it: a boy who gets to grow up in a safe and loving home and one who doesn’t. Even as the people around him recognize that he’s in danger, there is little they can do except offer occasional solace. Everyone in the story seems to be hanging on by a thread. There’s discomfort at the end because there’s a sense of how little people can help and that there will be no sure safety for any of these characters. While there is much emotional and physical trauma in these stories, and while there’s often not a clean resolution, these stories are a map of survival and endurance.

There is beauty and hope, too, even if only in the smallest things, though hard won. A grandmother shows her granddaughter her collection of porcelain angels in “The Best Kind Of Light.”

“I like to think they’re looking out for me,” I said, touching the figure on the nose. “They’re beautiful. The shine of the porcelain, the pastel colors. I like to think about who painted them. I try to remember there’s nice things in the world.” (154)

In “A Little Arrhythmic Blip,” a woman covers her entire fence in silk flowers and bright colored yarn so that it is like she “had the whole rainbow binding flowers to metal” (156). Beauty and hope neglect these characters, so they must create it for themselves.

Some of these stories present deep trauma, and others are quieter, full of longing and loneliness. All are unforgettable. A mother and daughter develop photos together and face hard truths about their relationship. There are absent parents and women with violent, mean men. A woman opens a furniture store in the neighborhood she grew up in, longs for her grandmother, and wonders what comes next.

The collection ends with two stories following the same character, Layla, who meets a man at Home Depot and marries him. He turns out to be very different than he initially appears, displaying increasingly erratic behavior and violence. The last story in the collection picks up when she has finally escaped from him, and yet still, we witness violence enacted by a different family. However, this story gives Layla her voice in full, and her action offers some of the strongest redemption and sense of a safe future that we see in this collection.

Deadheading does what the best stories do; they hit hard and made me feel all the emotions—love and duty to the places we inhabit, hunger, anger, fear, longing for our loved ones, and a map of how to survive. Gilstrap gives her characters a powerful voice, spiraling into the deepest parts of their hearts, showing both their darkest motivations and the resilience of people who have become all too familiar with heartache.

Deadheading by Beth Gilstrap

Red Hen Press – $15.95 (Paper)

ISBN: 978-1636280004

Emily Webber has published fiction, essays, and reviews in the Ploughshares Blog, The Writer magazine, Five Points, Split Lip Magazine, Brevity, and elsewhere. She’s the author of a chapbook of flash fiction, Macerated, from Paper Nautilus Press. You can read more at www.emilyannwebber.com and @emilyannwebber.