Review by Jennifer Martelli

Review by Jennifer Martelli

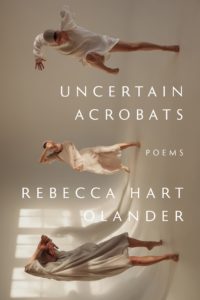

The poems in Rebecca Hart Olander’s debut collection, Uncertain Acrobats, not only recollect a father’s life, but also navigate the landscape of grief, making all movement breathtaking and physical. Olander’s mastery in her construction of the book belies whatever uncertainty or hesitancy the daughter—the speaker—has as she travels a world without her father. The poems are arranged so well, and with such precision of imagery and language, I trusted and moved with the speaker. The poems reflect the gorgeous image on the cover of the book: three women (or are they the same woman?) dancing (or are they falling?) mid-air in alabaster gowns. Olander describes the awful process of death, and the bewilderment of those left behind, as:

The gray-white shade of statues, and we are tourists—

doctors, nurses, aids, hospice, therapists, sons, daughter, wife

friends, clergy, palliative team—all of us looking to the ceiling

for answers . . . .

The first section of the book, learning to release, introduces the reader to the father. While the poems set us firmly in time, we also travel through it. Here, as acrobats, we need balance. In “Tickseed,” Olander writes. “. . . . How you suck me back/to a time when everything was alive.” In “Joint-Custody Commute,” the father and daughter speed across the Tobin Bridge, “a sweeping emerald scaffold for a roller coaster.” Olander introduces us to imagery that serves, not only as markers of time (Herman’s Hermits, Tab, Cyndi Lauper, Liz Phair), but to illustrate its passage. The empty stone bird feeder statue of St. Francis of Assisi, “waiting for wild rabbits and yard birds,/his concrete skirts always empty of crumbs,” evokes both physical and emotional hunger.

“But some things can’t be known until we know them,” the speaker says in “There’s No Place Like Home.” In this second section, no trampoline, we enter the “unknowable country” of death and after-death. Here, Olander navigates living in these two worlds, describing the grieving as “Uncertain acrobats, we tightrope between existing and/living. . . .” She uses the images of falling, of the sky, and of balance, throughout this section, almost unhinging it from the density of life in the book’s opening. This is a breath-taking movement, giving Uncertain Acrobats a physical dimension, that sense of dropping from a height. In “Glossolalia,” in an effort to imagine what the dying feel, she compares it to a fall:

partial loss pushing them to the edge of a skyscraper

they hold onto with only fingernails,

sure they will fall, and that there will be no trampoline. . . .

She, who is in one world, watches her father die, and wonders, “How are we standing for these standing orders?/How are you lying down?”

Olander uses balance in the final section of the book, riding the wind, opening with the poem, “Fool’s Gold,”

You fly at me, lurching memory, trapeze

artist, my pendulum. This swing dance, a trap,

the way summer slips into fall with ease.

Sometimes it hurts too much.

She continues with the earlier images of movement and hunger, reaching back around to the first section, almost reaching closure. The hunger in the first section becomes the hunger of death. In “Feeding the Dead,” the speaker asks, “What is it that eats us alive? So hungry for us/that it leaves holes in the world afterward?” The dead, too, are hungry; the poem ends with the heart-breaking statement, “I wanted my father to stay, but maybe his mother was more ravenous.” The daughter’s hunger and grief transform into a type of salvation. In “Visitation,” she writes

I grasp for more

but it is crumbs left in the wood,

glinting in moonlight,

illuminating the way,

no matter how hard I try to get lost.

As I read Uncertain Acrobats, I kept returning to the images on the cover. Who were these figures? What is their dance? From whence do they fall? Are they weeping? Are they ecstatic? Like these women, the poems in this collection reflect grief, in all its transformations. Rebecca Hart Olander has written a physical account of death and its horrifying, humbling wonder. She has written a book tightly structured and firmly planted in the world, allowing us to move and fall and weep. She has brilliantly met the painful task of witnessing death and trying to capture it “with letters of diminishing graphite and ink, book bindings that disintegrate as I navigate, searching for your hand in the margin.”

Uncertain Acrobats by Rebecca Hart Olander

CavanKerry Press, 2021, 18.00

978-1-933880-88-4

Jennifer Martelli (she, her, hers) is the author of The Queen of Queens (forthcoming, Bordighera Press, 2022) and My Tarantella (Bordighera Press), awarded an Honorable Mention from the Italian-American Studies Association, selected as a 2019 “Must Read” by the Massachusetts Center for the Book, and named as a finalist for the Housatonic Book Award. She is also the author of the chapbooks In the Year of Ferraro (Nixes Mate Press) and After Bird, winner of the Grey Book Press open reading, 2016. Her work will appear or has appeared in The Tahoma Literary Review, Thrush, Cream City Review, Verse Daily, Iron Horse Review(winner, Photo Finish contest), and Poetry. Jennifer Martelli has twice received grants from the Massachusetts Cultural Council for her poetry. She is co-poetry editor for Mom Egg Review and co-curates the Italian-American Writers Series. Jennifer Martelli received degrees from Boston University and the Warren Wilson M.F.A. Program for Writers.