Review by Michelle Panik

Review by Michelle Panik

Kids and Cocktails Don’t Mix is a memoir of life in the highly desirable Larchmont area of Los Angeles, a place where name-dropping—of people, of neighborhoods, of private schools—is a sport and appearances are everything. Beginning in the 1960’s and unfolding chronologically, daughter Heather tells of a family furiously polishing the facades of a reality that readers quickly learn is drastically different.

With a philandering father, a spouse-pleasing mother, and two completely opposite daughters, the Eatons are hardly a cohesive, thriving family. Younger sister Heather is an overweight, poor student forever trying to win her parents’ affection, while older sister April is conventionally beautiful. Their mother, Marilyn, encourages April to accentuate her physical beauty, as evidenced in an exchange while April is dressing:

“Stop!” April scolded Mom when she pulled down the ring on the front zipper of her top to show more cleavage.

“You won’t get Bobby’s attention all zipped up to the neck.”

April pulled the zipper up to reveal just her clavicle. “Don’t say that!”

Mom shrugged. “I give up. You do it your way.” (23)

Marilyn believes men are the answer to financial and emotional security, and she instills this in her daughters. And while this is a memoir of a family in tumult, Marilyn and Heather’s mother-daughter relationship is given the most weight. It is, indeed, a fascinating one. While Marilyn praises April’s beauty, she worries about Heather’s weight. Not wanting to anger her mother, Heather resorts to sneaking indulgent foods, writing, “If [Marilyn] saw me, a flash of anger would appear in her clear, light-blue eyes” (4). Marilyn also criticizes Heather’s grades; even things as inconsequential (and out of Heather’s control) as the size of her feet are chastised.

Each chapter begins with a quote from Marilyn—most about family, and most judgmentally terse—as if mother is forever watching daughter. The book’s title comes from one of these quotes, and readers learn that no one in these pages mixes well with cocktails. Marilyn is frequently in bed with a drink and the telephone, debriefing friends about the latest indiscretion of her husband, Bob, which often includes alcohol. This is a book where people, unhappy in myriad ways, turn to alcohol and drugs. And yet, addiction is never directly written about with any breadth, perhaps because it’s so pervasive as to be unremarkable.

Heather’s difficult relationship with her father is also explored. After Bob and Marilyn divorce, he marries an enormously wealthy friend of Marilyn’s. In a scene that’s suspensefully drawn out, readers learn that Bob wants to legally disown his daughters. Afterwards, Heather writes, “If I’d been nicer or more polite, maybe I’d still have my dad. But it would have hurt Mom. I couldn’t hurt Mom. Kiss up to the woman who had hurt and betrayed my mother? Never” (229).

Such thinking rings true to an abandoned, heartbroken, pre-teen girl. But, the adult Heather no doubt understands that this incredibly complicated situation was not her fault, nor could better manners have fixed it. And so, I was left yearning for her present-day thoughts to better flesh out these family dynamics.

Still, where the story occasionally falters from a lack of deeper analysis, its on-the-ground, stenographic style places readers immediately and firmly in each scene. When Heather bumps into her father at a party after not seeing him for a decade, the situation is intimately, fervently portrayed.

Throughout the memoir, the 4,500-square-foot family home looms large. Although nestled in an exclusive community, without the money for upkeep, it falls into disrepair. Corners are cut with cheap housepainters, increasingly simpler housekeepers, deferred plumbing and pool maintenance, and a gardener who only tends the front yard. Marilyn must repeatedly fight to keep the house, with the author remarking, “In a way, 127 Fremont Place had become one of her husbands, and at 57, my mother was hanging on for dear life, like Scarlett O’Hara hanging onto Tara” (268). In the end, Marilyn sells, and the new owners raze the entire structure.

In this way, the house is a metaphor for a family who, despite all attempts at salvaging relationships, ultimately accepts defeat. And where the author writes frankly about her family’s shortcomings during her childhood, she brings compassion and forgiveness to her adult relationships with them. This is a compulsively readable memoir wherein a wildly likable character triumphs over her broken family to experience truth growth and genuine happiness.

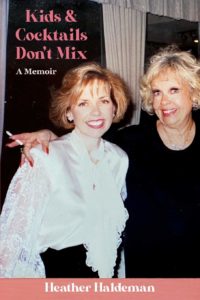

Kids and Cocktails Don’t Mix: A Memoir by Heather Haldeman

Apprentice House Press, 2021, $19.99

9781627203364

Michelle Panik is a writer and ESL teacher who lives on the edge of California, in Carlsbad, with her husband and two kids.