Review by Lara Lillibridge

Review by Lara Lillibridge

At age thirty-five, Cassandra Lane found herself pregnant after a lifetime of saying she never wanted children. She wrote, “my pregnancy boomeranged me back to my family and our past,” (25) and reawakened a need for her ancestor’s stories, a desire to know her people, long ago erased by white culture.

“This work is a hybrid—a romance and a horror, a memoir and a fiction—forged out of what is known and what is unknown.” (1) Lane’s memoir blends her personal narrative with a reimagining of the lives and deaths of her great-grandparents, Burt and Mary Bridges, alternating between the present day and the early twentieth century.

Burt and Mary’s story is a tale of young love, gestation, and lynching. While Mary was likely still pregnant with Houston, Burt had been lynched in Mississippi in 1904. Many in our family did not know about this legacy. I did not want my child to be likewise blind to it—and to its lasting impacts. (26)

Lane intersperses chapters of her life and search for love with the story of her great-grandparents—an exploration of inherited trauma combined with the ongoing trauma she experienced living in the white supremist culture of the United States.

Psychologists call it “trauma ghosting”—the body’s ability to “remember” a trauma that happened earlier in life or in an ancestor’s life. It can manifest as an extreme and inappropriate reaction to anything that “reminds” the body of that early trauma. (20)

Unfortunately, the racism of our culture provides plenty of opportunity to remind her of the earlier trauma. But by reimagining the story of Burt and Mary, Lane reclaims the narrative, and gives them a forever home in the pages of her book.

I said his name and wrote it into existence. As far as I knew, there was no gravestone carved with his name, no material proof. There were no birth or death certificates. There was no record of his and Mary’s love, no photograph, no yellowed note. (27)

Beyond her great-grandparents, Lane also explores her mother’s failed relationships and writes unflinchingly about her own divorces as well. Cassandra (Sandy) writes about her yearning for her absent father, and how she came to terms with the relationship:

Yet as I carried my child, his grandchild, in my body, I realized I no longer hated my father. Trying to protect my child from ancestral trauma outside of my control might have been an impossible feat, but what I could control, I believed, was the effect of my father’s baggage on my parenting. (167)

Lane is merciless in examining her own life and failings, yet offers a breath of mercy for her father when she wonders:

Did someone crush his spirit, and if so, at what point? Was it someone he knew and trusted? How did his country put its knee on his black neck and at what point? When he was a teen or younger?

Surely, he was not always a perpetually tormented soul who wreaks havoc on other souls. (167)

As someone who has plenty of father-baggage of my own, this theme really moved me. I admire her willingness to let go of past wounds, and took hope from her that it is, in fact, possible. Through the pain contained in the pages of We Are Bridges, there is always this movement toward hope, as the author’s pregnancy connects her ancestors to her offspring. As she details in a journal entry:

MAY 30, 2007

I smell of sweat and overripe fruit. Inside my body live both my dead ancestors and my unborn offspring. It is the decision to give birth— that process of carrying and delivering my child—that connects me to my past. My body is a river, a channel. With Solomon’s birth, Burt will live again, breathe again. (232)

Lane doesn’t shirk from writing about her own abuse and childhood woundings, and she writes honestly about her own regrets as an adult without excuses. Her voice is that of an imperfect, yet intelligent, introspective and likeable narrator. This book would be perfect for readers of historical fiction as well as memoir, as it straddles both genres.

Cassandra Lane is a writer and editor based in Los Angeles. Lane received her MFA from Antioch University LA. Her stories have appeared in the New York Times‘s Conception series, the Times-Picayune, the Atlanta Journal Constitution, and elsewhere. She is editor in chief of L.A. Parent magazine and formerly served on the board of the AROHO Foundation. (Feminist Press website)

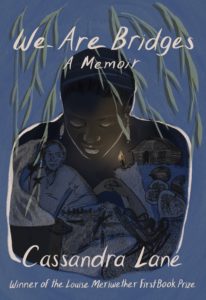

We Are Bridges: A Memoir by Cassandra Lane

The Feminist Press (New York) 2021, 243 pages

$17.95 (paper) ISBN 978-1-952177-92-7

Lara Lillibridge is the author of Mama, Mama, Only Mama (Skyhorse, 2019), Girlish: Growing Up in a Lesbian Home (Skyhorse, 2018) and co-editor of the anthology, Feminine Divine: Voices of Power and Invisibility (Cynren Press, 2019). Lillibridge is the Interviews Editor at Hippocampus Magazine and a mentor with AWP’s Writer to Writer program.