Review by Christine Stewart-Nuñez

Review by Christine Stewart-Nuñez

I usually don’t start a review of someone else’s poetry—especially such haunting work as Celia Lisset Alvarez’s—with a reference to my own experience, but I’m no stranger to writing about death, and Multiverses takes up loss, too: the loss of an infant, of a miscarried pregnancy, of a beloved uncle, of a problematic father. When I compare what I’ve had to say with Alvarez’s Multiverses, however, I feel cowardly. I avoided imagining futures for the pregnancies I’d lost because I didn’t want to grieve fiction, but Alvarez? She gives those fictions—those futures—entire poems. In doing so, she shows us what few poets can: how to live with profound grief.

The title Multiverses references the theory that our physical reality encompasses more than one universe. All the poems in Alvarez’s debut full-length collection are titled “Version” with a particular number, which indicates the narrative and particular version of said narrative. In the first version, twins Arturo and Sara are born at 27 weeks and Sara survives; Arturo succumbs to an infection. Also in that version, the speaker’s favorite uncle dies and the health of her papi, with whom she has a complicated relationship, deteriorates and he, too, passes away. But in other verses, both twins grow up to play at the beach with their older sister and meet their great-uncle. In other timelines, Papi holds his only grandson and the discord between father and daughter softens. This book feels revolutionary because grief compels us to as what if? but we rarely answer with written words. Braided with facts, these multiple versions explicate the significance of the loss, and the chasm becomes palpable.

In Multiverses the language of grief is plain, cutting through any mental distraction with a sharp directness. The short lines Alvarez employs slow the reader down so that each detail provides an extra second to hover over it as we apprehend it. The book opens with “Version 1.00:”

In the NICU,

they try to reassure me

with stories of babies

born at 23 weeks

who have survived

just like you and I,

no mark of this struggle

of wires and buttons,

dials and digital heartbeats. (1)

Directness doesn’t mean the poems lack craft, as they might for another poet; here this style creates a sense of immediacy and clears space for startling images infused with the power of grief. Later in “Version 1.00,” after giving readers a sense of the NICU room, Alvarez focuses on Arturo’s “big bulbous toe” (1), the only part of him not covered by tubes and tape, and she identifies the toe as a trait he inherited from her. This image appears again, and it becomes emblematic of the family connection theme that holds all the multiverses together.

Throughout the book, I noticed Alvarez’s sparse but powerful use of simile. I often see poets (including myself) using metaphor as a device of transformation, where one image shifts in quality due to its association. But Alvarez’s similes function first to clarify. In “Version 1.10”, she writes: “The day Arturo died the incubator / was open … / and he laid splayed out … / like a starfish” (12) to show how his body was situated in contrast to how we might have imagined, for example, an intubated infant or a sleeping preemie. Sometimes these similes convey profound clarification, as when the speaker hears “Arturito’s heart beating like a train” (30), but other times they provide a hint of levity as when the speaker describes her husband as looking “like Fred Flintstone” (18). Alvarez’s restraints in her use of the tools often used by other poets in excess amplifies the impact of her sorrow.

Alvarez breaks the narrative pattern in a few poems, juxtaposing them with more lyrical, fantastical poems. The experience of miscarriage seemed to be the factor in this shift. “Version 0.45” begins “Don’t write about the moon, / no one wants to hear such triteness” (33) but the poem is anything but cliché. The images of her uterus conjures the night landscape, and its subsequent emptiness after miscarriage draws out a litany of compelling comparisons. I appreciate how the poem holds anger in its sarcasm, an unromantic tone not usually associated with the moon. “Version 0. 46” carries a similar tone, but here Alvarez pushes the images into a surreal landscape where grief has caused the speaker to grow gills and breathe toxic air:

Should I perfect

these neat new lungs,

we will cease to understand each other.

You will look into my gold, transparent eye

and see no soul. No soul like yours. (34-35)

In poems such as these, Alvarez approaches grief with more fragmented language and speculative imagination, again showing the range of her skill and emphasizing the control in other poems.

This week, while writing this review, I stumbled across a video written by Megan Devine (www.refugeingrief.com) with advice on how help a grieving friend: acknowledge their pain. “Being heard helps,” Devine says. I connected it to the gift Alvarez has given us: a book that models how to confront grief—name it, describe it, reflect upon it—in all its rawness and reality. With Multiverses, we have a map to follow if we grieve, or the option to practice by acknowledging another’s pain when we’re not grieving ourselves.

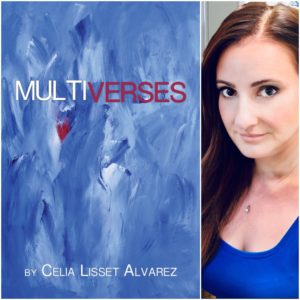

Multiverses by Celia Lisset Alvarez

Finishing Line Press 2021, $19.99

ISBN: 9781646624850

South Dakota’s poet laureate, Christine Stewart-Nuñez, is the author of Postcard on Parchment (ABZ Press 2008), Keeping Them Alive (WordTech Editions 2010), Untrussed (University of New Mexico Press 2016), and Bluewords Greening (Terrapin Books 2016), winner of the 2018 Whirling Prize. A book of poetry, The Poet And The Architect, is forthcoming from Terrapin Books. This professor of English at South Dakota State University just released a new poetry anthology, South Dakota in Poems. Find her work at christinestewartnunez.com.