Review by Julia Lisella

Review by Julia Lisella

This ninth collection of poetry by Andrea Potos begins, appropriately, with breakfast, perhaps the most mundane meal of the day, but also the most celebratory for its steady rituals. So, too, the poet’s relationship to the death of her mother. The book explores a grief that is at once deep and at times overwhelming, and also joyful in its power to resuscitate presence of the person who is dead. In the first poem of the book, “Breakfast Eternal” Potos sets the mood for the entire collection as the speaker imagines having coffee with her dead mother, who is seemingly at ease and having her Senior Special:

I love it here! she tells me again, isn’t Life

as certain as it ever was, she and I

face to face, drinking our coffee

black and filled to the top. (13)

What will it mean, the poet seems to be asking, to live in “this troubled world” (28) without the full presence of her mother? The answer is clear, though never pat: the mother remains very much alive.

The book is constructed as of one piece without parts or sections, and it is possible to move through the collection in a few sittings, offering us a kind of calendar of grief in which each moment is firmly rooted in specific places and times. Grief occupies a variety of landscapes—diners, gardens, grocery stores, and even beautifully surfaces in the many ekphrastic poems in the book. In the multi-layered “Partial Syllabus of Blue” constructed in long-lined couplets, the speaker takes us on a tour of naming: “Cerulean from watercolor skies”, “woad from the shrub Isatis tinctoria, kindred color/for monks illumining the Book of Kells;” and finally, drawn out in three beautifully balanced couplets, lapis lazuli, which Potos reminds us is “more costly than gold … / …and lit from invisible worlds / on the other side of seeing, or from the dreamed / folds of Mary’s robes.” (30). In nearly every poem the mother and what moves around and near her seems to light up with creative and mysterious energy, whether she is the speaker’s mother grocery shopping, drinking her coffee black, putting on her Revlon shade 712 lipstick, or this more familiar Madonna of renaissance paintings, the folds of her robes lit with lapis lazuli.

Grief in these poems is certainly real and challenging. In this poem in which the title serves as the first line Potos writes, “Grief in Summer / Is the deepest end of the pool/ darkest blue of the lake / … / It is the massive weight of sunflowers/crowded with seed” (21). The sunflowers are weighed down by their fecundity. In “Grief Fatigue” the poet writes of the relentlessness of grief:

Awake, some days

you carry it—

a gravity of notes

intoning through your bones

an almost forgotten

landscape—her voice

last heard

through glittering veins of stone. (31)

But it is through remembered cultural rituals, reworked for modern America, that the speaker fights this sheer fatigue. This cultural difference of the Mediterranean approach (references to Greek roots is mentioned in several poems) to death and memory is wonderfully expressed in the poem “For My Friend Who Told Me Don’t Fete the Dead”: “how can I tell him that every day I see her / smiling in her coral blouse, matching lipstick, and her sunglasses / sitting al fresco at our favorite Milwaukee café” (36). Angel and ghost sightings are common occurrences in these poems—the speaker’s daughter sees angels in the house hovering over the Singer sewing machine; her sister sees the mother at the checkout line at the grocery store; the speaker herself regularly has lunch with the dead mother.

The language in these poems is both accessible and fresh. Potos offers a couple of persona poems, each of them strong, for example, “I Saw A Light Mist Rise” in the voice of Louisa May Alcott, or “Goldleaf Maker.” Poems that mix various registers of sound and vocabulary also startle. In the closing poem of the book, “In Ireland, With or Without My Mother” the poet ponders, “Might she be these arrow-tailed magpies sweeping past, / these gorse bushes chiming everywhere with gold?” (59). Such gorgeous precise language buoys the poem’s final question. Could the mother be, “… these stars, these irrepressible stars / brighter than belief in the night?” (59). Though the book ends with this question, it seems to serve doubly as reassurance of presence, of life.

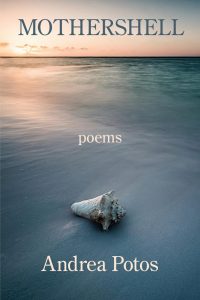

Mothershell: poems

by Andrea Potos

Kelsay Books, 2019, $14, paper

ISBN: 9781949229837

Julia Lisella’s poetry books include Always, Terrain, and Love Song Hiroshima, a chapbook. Her poems can also be found in Alaska Quarterly Review, Ocean State Review, VIA: Voices in Italian Americana, Antiphon, Literary Mama, and others. She teaches American literature and writing at Regis College in Weston, Massachusetts.