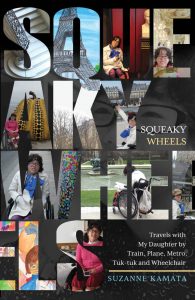

Squeaky Wheels:

Squeaky Wheels:

Travels with my Daughter by Train, Plane, Metro, Tuk-tuk and Wheelchair by Suzanne Kamata

Review by Lara Lillibridge

Suzanne Kamata grew up in Grand Haven, Michigan. She went to Japan to teach English, fell in love, and married a Japanese man. She gave birth to micro-preemie twins, one of whom was deaf and had cerebral palsy. Kamata recounts her struggles in learning to support and advocate for her daughter, while fostering independence at the same time. She writes about her first overseas travels to the US, and local trips around Japan. Kamata received a grant to fund her proposal to take her daughter to Paris and write a book about “accessibility and adventure.” (77)

Squeaky Wheels is an interesting multicultural conversation about independence and caretaking, but it’s also a conversation about being a multicultural family. Kamata speaks and signs Japanese with her daughter, but is very visibly American. There are many parenting moments she details that are just about the basic differences between herself and her husband

I want our children to be aware of possibilities, to be aware of the wider world, of cities and countries where they won’t be considered strange due to their bicultural upbringing. In other words, I want them to grow up to be international. Yoshi, meanwhile, is keen on nurturing their pride as Japanese citizens. (83)

This is a book about a mother trying to find her comfort zone between cultural expectations. It’s about finding the balance between being independent and accepting help. Kamata shows us her inner thoughts as she weighs the responsibility for advocating for her daughter’s right to access, and the knowledge that her decisions to fight or not fight will affect the next person in a wheelchair who follows behind her.

He is from a culture in which people abhor making a fuss. I, on the other hand, grew up hearing that the squeaky wheel gets the grease. If everyone kept silent, women wouldn’t be able to vote, blacks and whites would still use separate drinking fountains, and there would be no wheelchair ramps in the United States, either. (55-56)

There are benefits to traveling with someone in a wheelchair—some museums are free; many lines are avoided. Contrast that with the drawbacks, like inaccessible exhibits, or places where the “accessible” stall still has toilet paper mounted too high to reach from wheelchair.

I am often torn between wanting to do everything myself as a fiercely independent American, and wanting to ask for help, between being the squeaky wheel pointing out the injustices of the system and not wanting to make waves. (68)

Kamata pushes the wheelchair for blocks when taxis won’t stop for her. She carries her daughter up and down stairs at inaccessible attractions. She is mama-bearing her way through the vacation, until she realizes that she can’t keep up the pace. If she accepts help, they will be able to do more.

It would be easy to become bitter over the opportunities that are closed to them, but when she looks through her daughter’s eyes, Kamata is able to enjoy what they can experience.

Maybe I should try to be more like Lilia, who is often delighted by small pleasures: the flutter of cherry blossoms, the flicker of fireflies. I remind myself not to let my own disappointments dampen Lilia’s joy. (76)

Kamata explores the various ways the different cultures view accepting help, and the complexities of it. The hyper-attentiveness of Japanese culture meant that people always rushing to hold open doors, help, but they also prize not creating an obligation, so sometimes not helping is seen at the greater gift. In the US, we prize independence, yet still stress the need to speak out. Both cultures pull her simultaneously in opposite directions.

In France, she is urged to ask for help when she needs it, and when she does, the world often comes through for her. It’s a book that reaffirmed my faith in humanity. Kamata manages to remain profoundly human and avoids the dreaded “inspirational” story, yet still crafts characters we care deeply about.

About the author:

Suzanne Kamata’s short stories, essays, articles and book reviews have appeared in over 100 publications including Real Simple, Brain, Child, Cicada, and The Japan Times. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize five times, and received a Special Mention in 2006. She is also a two-time winner of the All Nippon Airways/Wingspan Fiction Contest, winner of the Paris Book Festival, and winner of a SCBWI Magazine Merit Award. (SuzanneKamata.com)

Squeaky Wheels: Travels with my Daughter by Train, Plane, Metro, Tuk-tuk and Wheelchair

By Suzanne Kamata

Wyatt-MacKenzie Publishing, 2019, $14.95 202 pages[ paper]

9781948018449

Lara Lillibridge is the author of Mama, Mama, Only Mama (Skyhorse, 2019), Girlish: Growing Up in a Lesbian Home (Skyhorse, 2018) and co-editor of the anthology, Feminine Divine: Voices of Power and Invisibility (Cynren Press, 2019).