Review by Lisa M. Hase-Jackson

Review by Lisa M. Hase-Jackson

In this, Mary Meriam’s third full-length collection of poetry, dreams are as integral to reality as are expressions of longing, immersion with the preternatural world, and politics surrounding gender identity. Relying largely on a variety of forms to deliver wide-ranging content, this book invites the reader to consider and recast the paradigms of all things feminine.

Early poems in the first section of the five that comprise the collection draw on dreamscapes for their potency, entreating in “Life Study” to

Let me not list, let me not repeat.

But come inside to my longing dreams

where hard work turns to soft love

and her hands hold my hips

that call for touch like loons on the lake (3)

setting a poignant tone of longing and unrequited love, the subject of choice for any good sonnet – modern or traditional – of which this collection contains many.

The motifs and general tone of desire are echoed throughout the rest of the collection and are particularly concentrated within an eleven-sonnet sequence that comprise the multi-part poem, “Sentimentality,” which follows close on the heels of “Life Study” in the first section, serving as a primary focal point. It begins,

The scent of unknown flowers in the breeze

filling my curtains, makes my heart beat fast,

faster and faster. Would you answer, please,

would you answer this soul, the flesh at last? (5)

The final sonnet of this sequence, “Spring,” closes with

The love I crave is cool and kind and slow

and how will I go on if she is gone

with never having breathed the air she breathes?

So chill me, wind, again, so I can grieve. (10)

securing this series firmly in the sonnet tradition as exemplified by Shakespeare and Browning.

Meriam utilizes rhyme schemes and measures akin to nursery songs and lore akin to fairy tales to cast overtones of the preternatural as illustrated in sonnets like “The Golden Box,” which begins,

I found a golden box on no one’s land

and put it in my pocket, mine to keep.

My box is small enough to hide in hand

and bright enough for company in sleep. (23)

Reminiscent of a child’s bedtime story, the narrative in “The Golden Box” strays away from the box imagery in a matter of a few lines to unravel into another dreamlike landscape wherein the speaker describes,

wearing our golden rings, the rings of ships

sailing and sailing swiftly over seas

full of the fierce sharp wind and sweetest breeze. (23)

That the tone of this and other poems is gently rhythmic and contains rhymes suggestive of innocence and easy subject matter, in addition to love and longing, should not lure the reader into taking this collection superficially for these whimsical moments are punctuated with poems like “Attack of the Fanatics” in which the speaker demands to know,

Did they question the men also?

Or did they only question the women?

The lesbians are policing the lesbians.

Who are you? How do you define yourself? (25)

Frustration over the constant demand to justify one’s essence and existence is as palpable and striking as the chill wind that accompanies grief, situating this poem squarely in conversation with current discussions surrounding gender equality. Chiming in, the poem “Odd Girls” asks, “Oh my darling girl / When did you learn how alone you were?” (56), a pertinent question for all women.

Meriam’s formal poems, which includes a crown of sonnets in the second section, go far beyond themes of love and longing to explore such subject matter as geography and the natural world, investigating persistent associations commonly attached to the feminine. These poems conjure images of witches (“The Earth”), Eve (“Godless), war, and even hell as in this poetic nod to writer Ali Liebegott:

Oh god of ocean, god of bed

strike it down and fold the flags,

and on the shore, the waves of dead,

wash them to sleep and bring instead

her puckered lips, not devils’ crags,

the hell it is, a hell I said. (46).

Meriam’s sonnet-writing prowess makes for enjoyable reading and provides many opportunities for whimsy despite their serious nature. And while her ability to find clever, often subtle rhymes is admirable, adherence to form at time interferes with a poems’ content and dictates direction in ways that free verse would not. Still and all, My Girl’s Green Jacket is a collection any lover of formal writing, and any woman who is interested in themes of gender identity, will want to have on her bookshelf.

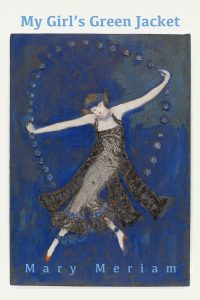

My Girl’s Green Jacket by Mary Meriam

Headmistress Press, 2018, 89 pages, $15.00 paperback

ISBN 9780998761084

A full-time writer, Lisa Hase-Jackson’s debut collection of poetry, Flint and Fire was chosen by Jericho Brown for the 2019 Hilary Tham Capital Collection Series and is forthcoming from The Word Works in March, 2019. She is the editor of Zingara Poetry Review.