Review by Judy Swann

Review by Judy Swann

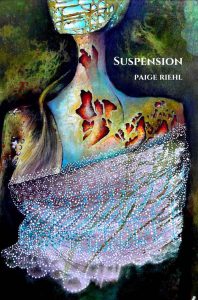

With its polyvalent title, Paige Riehl’s Suspension is the perfect hierophant for an exploration of the bridges between the self and the world. Many of the poems are about an international adoption, itself an image of nesting/nestling a poet-mother’s experiences into the loving act of parenting. The threads hang together, suspended like an oriole’s nest in which the children thrive. Then there’s the chemical sense of “suspension,” where undissolved particles of one thing are dispersed throughout another—truly the farrago of my life…yours too? And let’s not forget “suspension” as a stoppage or temporary withholding—not just as a rhetorical term (although check out “Apophasis” (19)) and not just a force that counters disbelief, but an invitation to consider the nature of time.

Time—and therefore both waiting and beginning—is of enormous concern to this collection. Let’s juxtapose the careful sense and sonics in “Wait” to those in “International Adoption Story: It Didn’t Begin”:

Had we known its connotations, the way a word

can rot like fruit

“Wait,” 36

It didn’t begin with despair

(or did it?). “Sign here”:

“International Adoption Story: It Didn’t Begin,” 7

As anyone who has struggled with infertility knows, waiting can disintegrate you. And so, in the word-poem “Wait,” the w falls off—in the way of things whose beginning, if there is one, is ambiguous. Then we consider the a:

the a—so outwardly tough

in its singularity—hollows like soft butter

under a finger

“Wait,” 36

Perhaps it began

further back—the loving in dark beds[…]

No. Before that must have been

glimpses and glances

hearts carried in pockets

and rubbed raw.

Our beginning is not. Not even

“International Adoption Story: It Didn’t Begin,” 7

A, before it fell, gave us a beginning. Without it we are truly beginningless, inhuman, like God. The unknowable beginnings of adoption give us pause:

and I am standing here

at this dinner party with the taste

of dirt in my mouth. Everyone

waits for the answer

“International Adoption Story: It Didn’t Begin,” 8

What remains is what we are waiting for: it.

But the t dives with arms spread wide,

a cross crashing on the shore

“Wait,” 36

The i is left on a bridge to nowhere, alone—or at least unspeaking—like the crowd on the ferry to Milos:

The saltwater, the sky, the same thick dark.

The rushing sound of the ferry,

as if the world’s doorway is just

opening, a suction of life slapping

in and out, an indecision

“Perhaps the World Centers Here on the Ferry to Milos,” 23

Here again we see the poet’s ear for music, the mastery of verse written for the ear. The ferry to Milos brings us its ironies—an ontology of beginninglessness, loss, and endlessness within the inevitability of time:

The lovers wait, hold their heads

in tired hands as the ferry tilts

side to side, time’s metronome

What lurks behind? What if

there is no destination and only dark?”

“Perhaps the World Centers Here on the Ferry to Milos,” 23

Maybe all that matters is “the quiet gathering of things.”(23) And so we turn to someone who’s been around, someone in the family, to see what to do. In “Ninety-Fifth Birthday” (51), Riehl writes:

She longs

for the past: chocolate cake heavy as the future, presents

with their small surprises. One by one, the people she’s known

have vanished like puffs of smoke. The past stacks up

around her.

In “Edie Watches the Tsunami from her Bed at Life Care Rehabilitation Center in Las Vegas, March 2011” (18), Edie couldn’t

see clearly enough to wonder about the people who must

only have had seconds to realize their own forecast,

the ocean rising up as if the world were quickly tilted,

death rushing toward them like a train.

At 95, Edie’s still listening to time’s metronome (as are we all):

At the dock, the bones stand up

and walk away without feeling dizzy.

They carry no fire or maps,

no awakening.

“Perhaps the World Centers Here on the Ferry to Milos,” 23

But soon, Edie will cross her own threshold. And “the waiting is strange,” the poet writes, as someone searches for enough river to wrap the dying woman in (74). The it that we waited for before has become something else. And we are still part of it. And it does not end.

Suspension by Paige Riehl

Terrapin Books 100 pages, paper

ISBN 1947896032

Judy Swann is a poet, essayist, editor, and bicycle commuter, whose work has been published in many venues both in print and online. Her book, We Are All Well: The Letters of Nora Hall has given her great joy. She loves. She lives in Ithaca, NY.