Review by Anne Britting Oleson

Review by Anne Britting Oleson

In many ways, this collection of prose poems is a horror story, spanning the life of a character living Thoreau’s life of quiet desperation. The pieces are dated (1887-1948), bracketing the existence of a fictional Iowa woman, from birth to death; that life is circumscribed by geography and circumstance, both of which create a sense of claustrophobia impossible to shake off.

Emily leads a narrow existence, not of her choosing. Reading this life from beginning to end, we are mired in Emily’s desperation. She is a thinking, feeling, exploring woman, but at every turn, her circumstances push her proverbial square peg into the round hole: this is where you are meant to be.

It doesn’t begin that way. The first piece, “Emily and the Ewes” (3), presents a fable of mysterious birth: according to Emily’s father, she was found naked in an orchard, protected from snow and cold by sheep. “I was his favorite,” Emily says of her father. Despite that, hints of Emily’s fate appear here: when her father questions the sheep about the baby they keep warm between them, “The old ewes could not answer in his tongue for they lived in time that had already passed.” He would not have been able to understand them had they tried to explain. The father’s story turns out to be untrue anyway: Emily is not a creature of myth at all. The real world begins to set in.

Silence and doom are themes which underlie much of Emily’s life. Often she is not heard: not her wants, nor her words. In “Emily on the Gold Coast” (21), though she is the best student, studying the encyclopedia until she imagines herself in faraway Africa, she is handed her certificate of completion of eight grades because “her mother thinks learning for a girl is foolish.” The irony, of course is that Emily’s mother “can’t speak English” (their insular Iowa world contains an even smaller Czech enclave), and forces upon Emily the same existence she herself lives: as a farm wife, housekeeping, livestock-tending, childbearing. Here the possibility of a further, outside world begins to slough away, for Emily and the reader, and the inner terror begins: is this all there is? Later, in “Emily and the Red Snow” (23), she laments “I practice my penmanship with a stick in the dirt. I’m missing roll call. Emily. Here.” Instead of standing up and being counted, she is trapped in her shrinking life: the fate of women in her community.

The narration of the prose poems shifts back and forth from first person to third; other women also are not heard. About her childhood best friend, who dies of diphtheria in “Emily and the Strangling Angel” (7) the narrator says,

“Annie’s throat is closing and the bluish membrane on her tongue spreads over her tonsils and pharynx. She no longer speaks and is silent like a tree whose thrushes and wrens have fled. Her eyes try to talk, to hold back the room that is slipping away….”

Forty years later, in “Emily and the Apparition” (67), Annie appears again, “between the fallen logs in the mushrooming woods,” and in death is still unable to speak. Though Emily is alive and Annie dead, the silence they share has become an equivalence, haunting Emily, while disturbing the reader.

When Emily marries, inevitably her husband, too, does not hear her. In “Emily and the Snapping Turtle” (33) she, newlywed, goes picnicking with John; he catches a turtle, which he wrestles to the bank.

“Everything tried to speak at once: the willow lashing the brown water with its wands; the buzzing flies; the matchstick gnats. The snapper spoke loudest: it howled….”John,” I said softly, “I’ve made us a picnic lunch.” My meaning—do not hurt this being who lives in the nocturnal mud, thinking the same thoughts as his ancestors 4 million years ago.”

But John, not hearing, cuts off the turtle’s head. No howl; no protest. Both are silenced.

These fables string together stories of blunted words, blunted lives. The fable with the dead friend gives way to the fable of the dead chicken, in turn to the one of the dead turtle, to dead workhorses, to Emily’s dead child, and later, to her dead brother. The harsh world takes from Emily repeatedly. Each time she manages to right herself; however, as the years progress this seems increasingly difficult. There is courage in Emily, and grace, as she struggles to face the life she has been handed, all illustrated with Dickinson’s glorious depth of language. Yet every expression of that courage and grace also bears a kind of agony: the desperation at oppressive silence and inevitable doom.

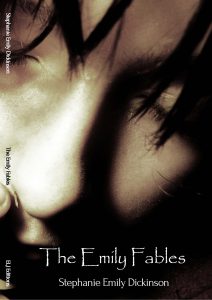

The Emily Fables

by Stephanie Emily Dickinson

ELJ Publications, 2016, $16.95 [paper]

ISBN 9781625579836

78 pp

Anne Britting Oleson lives and writes in the mountains of Central Maine. Her novels include The Book of the Mandolin Player, Dovecote, and Tapiser (forthcoming fall 2018); her poetry chapbooks are The Church of St. Materiana, The Beauty of It, and Alley of Dreams (forthcoming spring 2018).