Review by Christine Stewart-Nuñez

Review by Christine Stewart-Nuñez

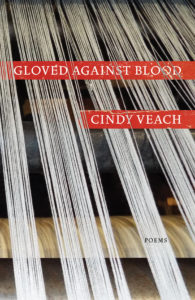

The title drew me to Gloved Against Blood. I admired its cacophony, how my mouth untangled the phrase; I admired its assonance, how the sounds “uh, uh” became onomatopoetic, suggesting pain. It prompted me to peel back the glove, reveal the hand. Even before I opened Cindy Veach’s debut poetry collection, the title ushered me into its world of sound and making.

Gloved Against Blood weaves generations of women bound by work, the physical labor of tending looms and the “close work” of stitching and sewing. Veach gives us a sense of the first generation by setting poems in the textile mills of Lowell, Massachusetts. “How It Resists,” for example, describes crowded looms with “their stanchions of white thread / spooling like udders” (3-4). The female imagery here surprised me—this is a mill, not a farm—yet it fits gracefully, and Veach picks it up again at the poem’s end: “the whole mill howls / as if cotton were milk” (16-17). Furthering the sound of work, Veach embeds the looms’ repetition in poems like “Great Red Wall” where iambs stack one upon the other like the bricks they describe: “red brick on brick on brick / is all that’s left of sweat and linty lungs” (6-7). When the mills transform into offices, cafés, and “cute boutiques / with clothes made in Bangladesh” (9-10) the rhythm shifts, too, a subtle variation that supports its artful meaning.

Despite the deafening looms and dangerous working conditions, Veach imagines the promise of the mills, especially for women like Mémé, who emigrated from Quebec to work in them: “I’ve seen the steps she climbed each morning to begin another day / in the mill. They spiral like a beaded periwinkle / / toward a far-off rectangle // of light” (“Triptych: Travaux d’Aiguille” III: 1-4). Readers get a sense for the intensity of the mills—and a saturation of skillful sound—in “Theft,” told in Mémé’s voice:

How I came down from Quebec to work in the mills

How I never imagined it would be such hell. How industry.

How factory bell. How many miles of cloth I conjured

from bloody cotton. How my eyes couldn’t get enough

of the one window—the Great Out There. (1-5)

Veach invokes the labor of other women—paid meagerly or enslaved—that contributed to this industry as well. “Lowell Cloth Narratives,” for example, includes testimony by ex-slaves who worked in textile mills. And in a haunting ghazal, “Dear Francis Cabot Lowell,” Veach critiques the industry founder: “They bleed I weave. I weave they bleed. Why can’t / you see—blood threads your looms all down the row?” (13-14). I appreciated the research that informed these poems and the skill with which it was rendered.

Veach threads her search for these women’s stories throughout the book. In “Predators,” Veach writes: “I’ve wandered online / searching for my lineage, / the unquiet room / of looms,” (19-22) and “I want to know / how things turn out // although even now / I’m forgetting them” (55-58). “Like Her” traces the way the speaker is similar to “Nanny” through the movements of stitching and ways of thinking that unite them. I admire Veach’s quest most in poems like “Thimbleful,” which begins: “If the mill girl in the daguerreotype is a stranger / than this nine-patch is an old friend” (1-2). Midway, the quilt reminds the speaker of an heirloom thimble that “protects me from the quick stick / of sharps and between” (20-21) and also transforms into “a vessel, repository, crèche / for the spiraled remnants of their making” (22-23). Imbued with so much as the poem unfurls, the thimble connects three generations through work. “French Seams” witnesses the “meticulous, unrivaled” (13) craftsmanship of the women, as well as their vulnerability: “French seams— // seams that hide raw edges / within the seam itself” (2-4). Part of their vulnerability is exposed by marriages that, despite the wives’ tenacious attention, couldn’t be salvaged. In fact, a keen absence of men marks Gloved Against Blood. “Curating My Grandfather,” for example, asks: “How do you curate // a man who vanished // into thin air?” (6-8). In “Absent,” Veach writes that he left “as a tree / splits, // cleaved / to the quick” (17-20). This lack doesn’t diminish, however; it strengthens the women’s stories and gives Veach another opportunity to spin her gorgeous images from history and hard-won reflection. I recommend Gloved Against Blood for any reader with an affection for poetry.

Gloved Against Blood

by Cindy Veach

CavanKerry Press 2017

$16.00

978-1933880648

Christine Stewart-Nuñez is the author of four poetry collections: Untrussed (2016), Bluewords Greening (2016), Keeping Them Alive (2010), and Postcard on Parchment (2008). Find out more about her work at christinestewartnunez.com.