Review by Grace Gardiner

Review by Grace Gardiner

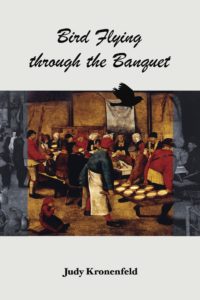

The title of Judy Kronenfeld’s fourth full-length collection Bird Flying through the Banquet alludes to a metaphor for existence posed by the 8th century English monk Saint Bede the Venerable in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People. In this seminal text on English religious history and identity, Bede describes “[t]he present life of man upon earth” as brief, rich, and mysteriously bounded as the flight of a sparrow through a warm and lively banquet, the bird first escaping, then (un)willingly returning to the cold winter night and its storms.

Kronenfeld, who is Lecturer Emerita at the University of California at Riverside’s Creative Writing Department and an author of poetry and criticism alike, sets up her collection meticulously well with this metaphor. Indeed, the collection’s seven sections—“Lives of the Dead”; “Beyond Request”; “Not Overly Suspicious”; “The Play of Attention”; Nothing’s the Matter”; “The Braille of Evening”; and “Gliding in the Dark”—speak to the divisions of leisure and eating, drinking and dancing, singing and speech-making, even sparring and sobbing, that might occur during both a literal banquet as well as this banquet’s metaphoric partner, a life on Earth.

The bird flying through this book’s banquet, however, is not simply an investigation of mortality: What does it mean to live? To die? How do we do either of these infinitives well? Rather, this book’s bird is memory and the ways in which memory ripples through physical, emotional, and cultural experience: memory of place, nationality, kindred, language, touch.

Consider the opening to “Beyond Request,” found in the eponymous second section:

One of the bed pillows . . .

. . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . .

leans over, soft as

snow on snow, and kisses

her waist as she bends forward to lift

her novel from the dresser,

and she thinks

in the second

her eyes close

he’s removed a hand

from his mystery

to rest on my lower spine. (31)

Here memory powerfully pushes out from its own interiority and abstraction into the speaker’s physical reality. This memory of the speaker’s bedfellow’s touch interrupts, then transforms the speaker’s situation and experience: “How naked / her stiffened back / now, in her flannel gown” (31). A pillow may be responsible for the literal touch, but the remembered touch initiates the stronger, more sensuous and sensory—and therefore more significant—implications of desire and sexuality.

As might be expected with titles such as “Lives of the Dead,” “The Braille of Evening,” and “Gliding in the Dark,” the collection’s opening and close concern grief for deceased loved ones, as well as for departed past experiences, as a probing of the mind and its memories. Kronenfeld’s language holds a precise, balanced tension against its lines in more tightly constrained poems like “Beyond Request,” but the looser, lusher form of the prose poem illustrates not only the myriad mechanics of the mind, but also the imaginative force of memory within that mental machine.

“Resident Dead,” found in the collection’s penultimate section, is one such prose poem that moves from grounding images of “mylar balloons, butterfly pinwheels, porcelain lambs . . .” to “[t]he old velour robe, the hospital booties, the floral nightgown . . . mildewed into juice . . .” to “Jehovah bending close to breathe on some random handfuls of dust” (80-81). The speaker’s literal movement—driving past the cemetery where their mother has been buried for many years—is juxtaposed with the ever-increasing imaginative movement of the speaker’s physical, emotional, and cultural memories: the graves’ decorations, the remembered past and perceived present image of the mother’s corpse, the vision (whether believed or disregarded) of the divine.

Another prose poem, “Avis Poetica”—found in the collection’s fourth section “The Play of Attention”—makes the most direct connection between memory and the collection’s titular bird-banquet metaphor. The poem is an obvious play on the self-referential ars poetica, in which the poem’s speaker uses bird imagery to illustrate the various movements of their creative process. In the final prose stanza, the speaker encounters a literal bird after having to “make up” or “key in” various imagined specimens: “Eye-corner flicker. Wait. Something has pushed off from a rebounding twig of the Japanese plum, with a knife toss of glittering wings” (60). In the poems of Bird Flying through the Banquet, this is the exact manner in which Judy Kronenfeld allows and prompts memory to enter into her speakers’ investigations of loss and life—“glittering” as briefly as the bright knife of a bird’s wings.

Bird Flying through the Banquet

by Judy Kronenfeld

FutureCycle Press (2017), $15.95 [paper]

ISBN 9781942371236

102 pp

Grace Gardiner is a recent graduate of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro’s MFA Program and a former poetry editor for The Greensboro Review. Her work has appeared in The Adroit Journal, burntdistrict, and Forty Eighty-Five. In the fall, she will begin pursuing her PhD at the University of Missouri, Columbia.