Review by Jennifer Martelli

In the twenty Elizabethan sonnets that make up Infinite Collisions, Issa M. Lewis explores family, home, progress and time. The narrator asks, “What holds a house together?” (Sonnet X, 15). Land is carved up and tamed; homes are built and demolished. One family, beginning with farmer “C” and his wife, “A,” leave their mark on the land, beyond the village of Grass Lake, Minnesota. Starting in pre-World War II America, through the war, up to the present time, the consistency of the poetic form—the sonnet—is the life-blood coursing through life’s vicissitudes. In Sonnet X, the narrator says

Then we pour ourselves into the blank space

between doorways: the start of our lineage

like sunlight through curtains of tea-dyed lace…. (15)

The space in Infinite Collisions is not only the home and farm built by C and A, but the poetic form used by the poet. By choosing the Elizabethan (or Shakespearean) sonnet, Lewis claims her own poetic heritage; and like the homesteaders, demands the language, like the land, be tamed. Each poem conforms to the structure: three quatrains, with a closing couplet, following a rhyme pattern. Thus, a rhythm is formed, almost seasonal or tidal, as you read the book. There is consistency, but also the satisfaction of having completed, or filled, a structure. This adherence to form is pushed up against, also. If the sonnet is used as a way to reach back to an older way of writing, time has other ideas. Sonnet XVI’s final quatrain and couplet challenge such nostalgia and stasis:

And on a town, also, the years take

their toll. The buildings grow, the people come

to put down roots and make their home Grass Lake.

Fields spread, and roads entwine like lamb’s wool spun.

The inevitable transformation

for better or for worse, no cessation. (21)

The dismantling becomes a physical act, just as completing a sonnet is. As the poet fits words correctly into the sonnet’s line, the next generation, D, dismantles the structure:

…grabs his tools, begins to peel away

the shingles like pages of a yearbook.

He tosses them to the ground, where they lay

in piles, small slices of seasons long gone

remembering the rain, the snow, the sun. (Sonnet XVIII 23)

This collision of form and resistance to form, of building and destroying, can also be found in Lewis’s rich imagery. She entwines the land, the home, and the body into a triple helix, like strands of DNA. In Sonnet II, C describes the land as “green, rolling acres begging to be sown/with any seed to find a womb” (6).

As he is building his barn, the beams are “reaching up to the sky like ribs (Sonnet III 7).” The newly-build road has a tongue and is tattooed “It came to give. It also came to take” (Sonnet V 9). The humanity inherent in C’s and A’s home makes its destruction all the more poignant.

There are faces in the walls–not just pictures,

not the frames, the walls themselves are full

of memories; one brother three sisters:

D’s children, and his wife’s…

Are they ghosts? No, but whispers low and true

of what has been. A pen in hand records

each day…

Every brick and plank of wood in this place

holds tightly to each memory, each face. (Sonnet XV 20)

Issa M. Lewis, as deftly as the matriarch A stitches an American flag while her son is at war, fuses worlds: old and new, town and country, living and dead. Recording is never easy, “But only when she sets the blue star’s place/does she drop the needle, hide her face” (Sonnet VIII 13). By integrating the organic and the man-made within the structure of a strict form, Lewis replicates an old life-line, reaching back, while being moved forward, through time. These are poems that pulse through our veins, like blood. Infinite Collisions succeeds, not only in its clarity and weaving of story, but on a physical level, which is where poetry is always most pure.

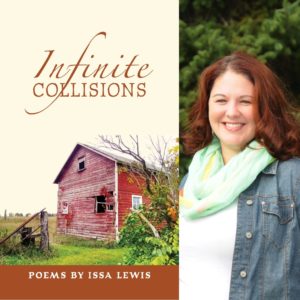

Infinite Collisions

Issa M. Lewis

Finishing Line Press, 2017, $14.99 [paper]

ISBN 978-1635341812, 32 pp

Jennifer Martelli is the author of The Uncanny Valley and Apostrophe, both from Big Table Publishing Company. Her chapbook, After Bird, is forthcoming from Grey Book Press. A recipient of the Massachusetts Cultural Council Grant in Poetry, Martelli is an editor of MER Online and is also a reviewer at Up the Staircase Quarterly.