Review by Bunny Goodjohn

Review by Bunny Goodjohn

Whenever I read Kim Addonizio, I feel a little jacked up, a little…dangerous. It’s as if I know she’s going to open a lid, not only on her world, her life, her family…but also on mine. Mortal Trash proves to be no exception.

Addonizio is the mistress of metaphor. In “Manners,” a poem to tear out and refer to as a map to the strangeness that is modern life, her narrator hands down advice that narrows into a stark image:

When the pulley of your childhood

unwinds the laundry line of your dysfunction,

here is a list of items to shove deep in the dryer:

disturbed brother’s T-shirt,

depressed mother’s socks and tennis racket,

tie worn by soused father driving the kids home

from McDonald’s Raw Bar… (38)

If we see minding our manners as a way of reeling in our impetuous and sometimes damaging inclinations, the “unwinding” in this metaphor is doubly glorious. It hands over this sense that life cannot always be sanitized by manners. Even when we do our best to clean things up (our decisions, our interactions, our families), they come out clean but not yet fit for the public eye. So we “shove [them]deep in the dryer” desperate for the machine’s dewrinkling, its artificially perfumed conditioning.

In my own family, manners were huge. Mum was adamant her girls would know how to behave, that we would be “mannered.” We were taught that girls were seen and not heard. This manner’s mastery left me struggling for a silent prettiness inside a tangle of questions that apparently couldn’t be asked in polite society. The speaker in “Review of Possible Signs and Symptoms” appears to be similarly burdened with questions. She opens with one of them: “I wonder if it’s a problem/that I still believe what I did at five:” (60). We don’t quite know what disorder is under diagnosis here, but something is quite obviously broken

There is definitely something wrong with me.

My piston can’t connect to my spark plug.

My kitty can’t leap to the branch of that tree

the way the squirrel does so easily(60).

The examination of brokenness shifts from child to grown woman to elderly mother: three generations of silent breakage:

My mother couldn’t speak at the end,

only look at me with one dazed eye.

It’s normal to cry, lying in bed

with your dying mother. I wonder

if everyone’s head sometimes feels

like it’s pumped full of Styrofoam pellets.” (60)

If these two poems deal with a close examination of and a connection to specifics, “Florida” tumbles us into disassociation. A woman, naked on a stranger’s bed and stinging from his insults, wishes she could “dematerialize.” As she is “fucked backwards while facing a stain on the wall that resembled Florida” she disassociates so she might “wander in order to avoid being present” only to find herself at the hands of another dominant male, her “crazy violent older brother” (63). There seems no real escape, either from the torment of this stranger’s bed or from the deeper reaching nightmare of family.

In “Sleep Stage” we shift from disassociation to traditional dream:

In the dream, my mother could again

get out of bed, but only to stand

before a black mirror, so really

not a good dream after all (88)

The poem hands over that tricky mother-daughter relationship. Here, everyone’s dreams have been broken and only reality remains:

I maneuvered a spoon of green mush

but then skipped that and the squash

to give her all her pudding,

and went sneaking

to the bathroom to dump the remains

so the nurse wouldn’t know. Dreams,

what are they, anyway? (88)

I sense that Addonizio’s advice (which I take willingly) is that given the shortcomings of dreams, we might do well to flush life’s “green mush” down the toilet and order lots of pudding. After all, the only thing any of us is guaranteed is death. In “What to Save from the Fire,” after a long list of suggestions, Addonizio, thank goodness, continues to advocate for the sweetness of pudding rather than virtue of squash:

… look at those rosettes of self-pity

adorning the cake of your depression:

let the journals burn. Meanwhile

better wet a towel and hold it to your face.

Who’s coming for you? Hopefully large men

in helmets and boots, and not a few students

exhuming a metaphor. Stay calm.

Throw darts. Some look like cruise missiles,

some like honeybees.

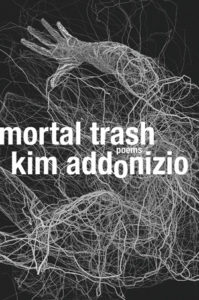

Mortal Trash

by Kim Addonizio

W.W. Norton, 2016, $25.95 (hard)

ISBN 9780393249163

Bunny Goodjohn, originally from the UK, is the Book Review Editor at Mom Egg Review. She is the author of two novels, Sticklebacks and Snow Globes (Permanent Press 2007) and The Beginning Things (Underground Voices 2015). Her first poetry collection, Bone Song, was published in May 2015. She directs the Writing Program at Randolph College in Virginia. www.bunnygoodjohn.com