Review by Janet McCann

Review by Janet McCann

The title The Language of Little Girls instantly set loose an earworm for me, that being “Thank Heaven for Little Girls.” But this refrain did not stay with me even through the first page of the book. The girls and women in this collection are not delicate sentimental creatures, but rather fascinating and sometimes alarming women steeped in the lore of the female, connecting up with nature in unexpected ways. Kate Falvey is on the editorial board of the N.Y.U. Bellevue Literary Review and is editor in chief of the 2 Bridges Review. She teaches at New York City College of Technology/CUNY, and her poems have been published in many print and online journals. She has published two chapbooks, What the Sea Washes Up and Morning Constitutional in Sunhat and Bolero, and this is her first full-length collection. This book is full of girls and women of all ages, speaking and spoken of. The female world that emerges is fascinating, and gives the lie to preconceptions. Some of the poems are hilarious and disturbing. In “The Language of Little Girls: Doll Babies” Falvey describes two children playing with their dolls Connie and Marilyn:

Hunched in the bedroom, we splay Connie and Marilyn

on a bed of rough mulch and wings of fern which

Mrs. Dawson would flip if she knew we scooped and tore.

Connie has a head wound and Marilyn hurt her spine.

We dot rashy zigzags and pulpy clots of blood with blood

from our own scraped ankles and shins onto the blushing

rubber of their girly skins. Then we are priests dishing out

atonements for all their ragged, prissy sins. (13)

It reminded me of my own preschool days playing French Guillotine with my paper dolls, and my boyfriend. (How did I know at four about the guillotine? Well, my mum, a French teacher told me.) But the voices in these poems are truly convincing. Catholicism is another major presence. Nuns haunt the poems, nuns who seem to represent denial of the self and the demands of piety, and the children’s response to the iconography of their faith is unnerving and fun. Their God “is a project/cut out in foil /and pressed into paste/on dark red paper” (3). The description of the project reflects the child’s perspective:

Tiger-lilies are the shapes of the flames and

this is o.k. because God is known

to enjoy his lilies. Hosannas are

at His feet. They are chubby and puffed

and stunted in pink attitudes of glee. They have

horns instead of rattles and they make a fat

harsh invisible noise like babies squalling

into gurgles. (3)

The child’s matter-of-fact acceptance of her world, even when she is not understanding it, is a delight. Her interaction with water and land, her best friend, solitude and society give an original refreshing vision. Not all the inhabitants of the book are children, of course; there are adolescents, folktale women, grandmothers, women starting out on their adult lives, and some women whose age is indeterminate. There are studies of women role models and the lessons drawn from them, enlightening or otherwise. Some of the poems interrogate the expected roles for women and examine the mythologizing process that has conditioned them all. In “Gingerbread Mix,” the mythic kitchen seduces even the woman who rejects it:

Pound cake, angel food, puddings, meringues, and

breads with a hint of cardamom —

There is, in my hurried resurrection of

kitchens of yore,

the fairy dust of sifted flour,

oleo and oats, the crisp dither of brown

sugar rasping golden oaths,

the whir of my mother’s mixer,

the rim of a ceaseless day,

the untrammeled joy of licking

the bright and mystic blades. (71)

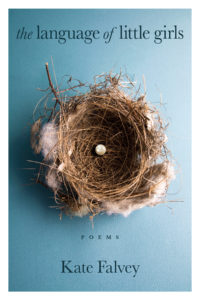

A particularly appealing poem describes a reluctant friendship between an Italian woman and a Middle Eastern family, both poor. This is a dramatic monologue by the Italian grandmother who has been feeding the two little girls, Nasreen and Saba, and teaching them English; the girls’ mother gives her a cake which she interrogates before consuming, then accepts as much like her own “before I got/ too old to beat the eggs” (38). A few old black and white photos illustrate the book. These slightly blurred photos of the past make the vivid language of the poems stand out, and give us a feeling of how memory works. There are few current poetry books that are truly hard to put down, but this is one of them.

The Language of Little Girls

by Kate Falvey

David Robert Brooks, 2016, $19.00, [paper]

ISBN 978162491930

95 pp

Journals publishing Janet McCann’s work include Kansas Quarterly, Parnassus, Nimrod, Sou’wester, America, Christian Century, Christianity And Literature, New York Quarterly, Tendril, and others. A 1989 NEA Creative Writing Fellowship winner, she taught at Texas A & M University from 1969-2016, and is now Professor Emerita. She has co-edited anthologies with David Craig, Odd Angles Of Heaven (Shaw, 1994), Place Of Passage (Story Line, 2000), and Poems Of Francis And Clare (St. Anthony Messenger, 2004), and written scholarly books and textbooks. Most recent poetry collection: The Crone At The Casino (Lamar University Press, 2014).