Review by Deborah Hauser

Review by Deborah Hauser

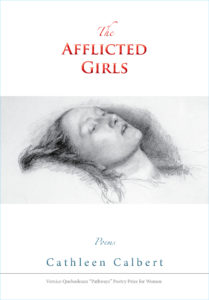

Cathleen Calbert’s fourth book, The Afflicted Girls, which won the Vernice Quebodeaux “Pathways” Poetry Prize for Women, is part history (though not meant to be historically accurate), part tribute, and part social critique. The collection opens with “First Wife,” a dramatic dialogue in the voice of Lilith, and closes with “The Princess Bride,” a tribute to Calbert’s friend. In between, these pages give voice to an array of women from Florence Nightingale to Zelda Fitzgerald in a variety of styles. “Talking Cure” and other poems use found language. “At Chawton Cottage” and “′The Misses Bronte’s Establishment for The Board and Education of a Limited Number of Young Ladies′” are personal narratives that connect the speaker to the women and explore our attraction to them.

Comparison to Carol Ann Duffy’s The World’s Wife is inevitable. Both books present a compressed history of the world from the point of view of women. Despite the similarity, Calbert’s handling of the subject is completely unique. There is less the sense that the women in Calbert’s book are speaking in relation and opposition to men and more of a feeling that the women have finally claimed the agency to speak for themselves. Most of Duffy’s “wives” are fictional (Mrs. Midas, The Devil’s Wife) and the retellings are clever with modern twists. Calbert’s girls are real people (Jane Austen, Marilyn Monroe) which elicits more pathos in the reader.

It’s exciting for the reader to discover the subject of the poem when it isn’t announced in the title, but occasionally frustrating when the subject doesn’t become readily apparent. Almost every poem has a Note at the end of the book which provides a source citation and additional context. This is of interest to the reader who wants to delve deeper into the lives of the women who speak in this collection, but it is entirely possible to read and enjoy the poems without referencing the Notes.

Women writers and women who suffer from illness are the subject of many of the poems. The cover features a sketch of Ophelia, and the book opens and closes with images of Ophelia. “Stunner” is a narrative of that “mad girl,” referring to both Ophelia and Elizabeth Siddal, the model who posed for John Everett Millais’ painting “Ophelia.” Calbert asks of Siddal the question she asks of so many of the women in this book including Elizabeth Bishop, Joan of Arc, Sylvia Plath, and more contemporary artists such as Amy Winehouse:

flirted with death, so you kept threatening to waste away. Consumptive? Anorexic? Another nineteenth-century lady with a medical mystery. (31)

Assumption gives voice to the Virgin Mary “who said little, and wrote nothing.” The power of words to create, and impregnate, is revealed:

she conceived, in a manner of speaking, via the ear, like a medieval weasel, through the word of the Holy Spirit Oxymoronic virgin/mother of Jesus and the rest of us, she wasn’t hot enough to be the lover of God the Father, (4)

“Assumption” winds its way down and back up in one long stanza that creates a back and forth tension between the biblical story we are familiar with and the poem’s irreverent version of the immaculate conception.

Calbert masterfully uses form to express content and skillfully uses indentations to create shape and movement. Form is most effectively used in “Dear Miss Dickinson,” which can’t be reproduced here, but zigzags down the page from the left to right margin in a dizzying display that mimics the speaker’s confusion about Emily Dickinson’s:

but it’s you that I want to grab a hold of

and make answer all my questions. Tell me,

Beauty’s kangaroo, Death’s girlfriend,

from our perspective in the 21st century,

how would you classify your problem? (26)

The poem is a direct address to Dickinson in which the speaker rapidly fires question about the poet’s life, work, and illness, and confesses: “I don’t know what you mean” (27).

In “Mata Hari,” the same form dazzles the reader as it enacts the exotic shimmy of the femme fatale who “turned sexy into tragique/as a thousand curves of her body/trembled in a thousand foreign rhythms” (45).

In the title poem, the women persecuted in the Salem Witch trials collectively speak of the power of speech and knowledge: “the fault that of the Father of Lies,/who improved out tongues/to speak of things we knew not of” (10). The women wield their newfound power against each other:

They seized the Scold, Troublemaker, Quarrelsome Shrew and hanged her at our word as if we were men or queens. We swore before the Congregation that we would become Good Wives, (11),

Fortunately, there are no “good wives” inhabiting the pages of this sensitive and illuminating study of history’s “afflicted” women. Their voices deserve to be heard. Their stories are bewitching.

The Afflicted Girls

by Cathleen Calbert

Little Red Tree Publishing, LLC, $19.95 [Paper]

ISBN 978-1935656449

120 pp

Deborah Hauser is the author of Ennui: From the Diagnostic and Statistical Field Guide of Feminine Disorders. Her poetry has appeared in TAB: The Journal of Poetry & Poetics, Carve Magazine, HEArt Journal Online, and Antiphon.