Review by Bunny Goodjohn

Review by Bunny Goodjohn

Writers plunder, excavate, and strip-mine without regard for the consequences to others. They suck their loved ones dry of vital fluids, revealing their deepest fears and yearnings. They expose the most precious secrets of their friends and families, then take all the credit and get all the applause (10).

In the small space of this essay collection, Addonizio covers a lot of ground. She takes us to conferences with writers, on dates, and into dark tussles with vodka, good intentions, and compulsion. But it is when she sits us down with family that I feel the strongest connection.

Seated at her table is her mother, father, and several siblings. But there is no chair for her oldest brother. She explains, “My brother was angry and violent and [I knew] that, as the only girl, I was the weak one in the herd” (90). But even though he isn’t at the table, she acknowledges that he is definitely at her desk, nudging his way into her fiction which “comes partly from scraps of life stitched together in new patterns; trouble and conflict are its engines, and he is some of the trouble I’ve experienced in my life” (90).

This life begins in part with her father who ghoulishly wraps up childhood bedtime stories with “…and they all fell down in a pool of blood.” Addonizio assures us his improvised endings are lovingly borrowed from classical tragedy and that “the next night everyone would be back where they belonged, ready for further adventures” (18). That each adventure ends in slaughter seems no deterrent to their continual embarkation. Foreshadowing, perhaps?

Addonizio’s relationship with her father is wrapped in Rumi, escapades, and love. The connection with her mother is less easily defined. In earlier essays, we meet her mother as pure character: the 1946 Wimbledon Singles champion, the maybe lover of Spencer Tracy, the Duke and Duchess of Kent’s luncheon guest. But here in “Flu Shot,” in the Summerville Assisted Living center, her mother is no longer the celebrity. She is an old woman, depressed and sleeping her dull days away. Her focus has narrowed to Cheez-Its, and these provide bribe for a flu-shot. Addonizio cringes as the woman at the Minute Clinic inoculates her mother and wonders, “Does [my mother]feel humiliated, my mother who smells bad, who wears no bra, as the nice woman unbuttons her drool-encrusted blouse? No matter. I feel humiliated for her” (65). Addonizio has done what many of us do or prepare ourselves to do: she has shifted from child to adult and, in doing so, assumed the role (and emotional responsibility) of being a parent to her own mother.

She continues to explore this evolving relationship in a later essay suggesting that “[e]very child is born with a tiny part of its imagination missing, the part that can visualize Mommy and Daddy…naked and sweating together as all manner of obscene things occur.” It is only after her mother’s death that Addonizio is able to think of her mother “as a woman who was once a sexual creature” (71). She nails a common fear—or truth—here. As children, selfish and self-centered, we consider caretaker our mother’s only role. Then one day, often as teenagers, we realize that it is possible that last night our mothers and fathers went to bed…and made love: our parents shift in that moment from the nonsexual to the sexual. And in that shift, we begin the difficult process of encountering our mothers as ourselves.

For me, the culmination of this encounter was to push me to consider my own mortality and to panic a little at the prospect of growing old without a partner. In what is perhaps my favorite essay “How to Fall for a Younger Man,” Addonizio stresses over the possibility that an ill-conceived affair might be her “swan song” and that she will be “doomed…to start piling New Yorkers and Poetry magazines on the furniture, to huddle listlessly in a moth-holed sweater in a dark apartment, waiting to die and be eaten by [the]cat” (152).

Sad that I had reached the end of the collection, I closed the book, kicked two copies of Poetry magazine underneath the sofa, and threw the cat out onto the porch.

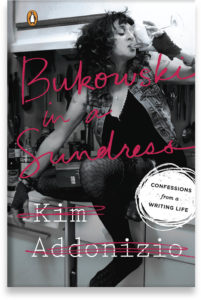

Bukowski in a Sundress

by Kim Addonizio

Penguin Books, 2016, $16 [Paper]

ISBN 9780143128465

205 pp

Bunny Goodjohn, originally from the UK, is the Book Review Editor at Mom Egg Review. She is the author of two novels, Stickleback And Snow Globes (Permanent Press 2007) and The Beginning Things (Underground Voices 2015). Her first poetry collection, Bone Song was published in May 2015. She directs the Writing Program at Randolph College in Virginia. www.bunnygoodjohn.com