Review by Libby Maxey

– Amelia Martens has published three chapbooks, but this is her first full-length collection of poetry. It’s a beautiful book in every respect, a true work of art. Her prose poems are short, most covering less than half a page, but they’re so dense and so full of the unspoken that my marginalia filled in most of the available space. The book is part of The Linda Bruckenheimer Series in Kentucky Literature, and Martens has won an Emerging Artist award from the Kentucky Arts Council, but there is nothing in these poems that feels strongly regional. They feel American (with poems like “Middle America,” “A Hundred Miles From the Border,” “Don’t Miss Our Mower and Tractor Spectacular,” and three different versions of “In the First World”); but Marten isn’t stuck in the south, or even the center. These poems set their feet in a field or a backyard or a bed; then they look out across the planet and pierce through the universe.

The two strongest currents in the book are parenthood and the sad state of the world into which we bring our children. Even so, the book feels more mystical than bleak. It makes cicadas into “Icarus confetti. Skeins of flight fallen” (54); it calls dying starfish “sea canaries” (33); it imagines a field as a thing that can “[lie]down in a patch of gods and [get]shot through the gut with cotton and wheat” (2). The collection includes a number of mini mythologies (“A Field,” “In the Land of Milk,” “Almost Biblical”) that are imaginative, surprising and charming, even though they’re stories of how far we’ve fallen, and how ungratefully we confront the incompleteness of our given lives.

There is a recurring daughter, young enough to be a “persistent chicken” for whom the speaker-mother sprinkles Cheerios (22), and her questions and demands and fears catalyze visions of a whole world hurting, fearing, needing— but also worlds unseen and inviolate: “There are some things you are trying to tell me, some things that can’t be burned” (2). On the bathroom rug, inviting her mother and the dog to close their eyes and “be dying” with her, the daughter opens her mother’s eyes to every detail of that ephemeral bathroom even as “the water level’s rising” (36). Living out our dying, there is a strange comfort in the moment’s small appreciation that “all colors make all things” (36). Martens’ seriousness can feel like a punch to the gut, but there’s a cheekiness that regularly resurfaces, lightening the burden of the absurd. The poem from which the book’s title is drawn, one of my favorites, at first sounds like a child’s nonsensical complaints against a life full of storybook disappointments: “You think you are the lost princess, but your hair isn’t long enough. Someone has been riding your giraffe” (42). By the end of the poem, however, the litany feels very much like the contents of the bag that every parent is left holding: “There is no explanation about the cookies. Someone has been wearing your clothes and they fit just right. In the event of a water landing, nothing you own will turn into a boat” (42).

The most fascinating feature of the collection is the series of seventeen poems interspersed throughout in which Jesus works the drive-thru, leaves a bar on a Wednesday morning, confronts a pile of mail, sorts buttons or hires immigrants to “brand the face of the Virgin onto grilled cheese sandwiches” (5). These odd and masterful pieces blend humor and pathos in a way that isn’t cheap or cynical, but rather thought-provoking and challenging. This Jesus works no wonders among us; he’s something closer to the everyday people in whom Christians are supposed to see the face of Christ: “Out back at the dumpster, he thinks about how to help. How he might offer napkins, thin as onion skins, and sweep the path clear with his palms as he hands over a grease-stained bag” (14). It’s painful to see even the Savior so helpless, but this is the Jesus who suffers with us through an existence that makes us want to fly away or bury ourselves. The bottom line is the Biblical truth that “all is dust” (43). Still, Martens makes the most of the dust she has to work with. I liked this collection more and more with every poem, with every revelation of “losses so fine we shed them with our skin” (53).

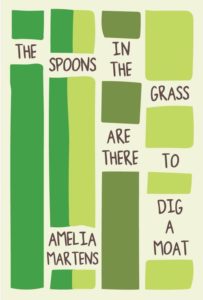

The Spoons in the Grass are There to Dig a Moat

by Amelia Martens

Sarabande Books, 2016, $14.95 [paper]

ISBN 9781941411230

Libby Maxey works as a freelance editor. She is on staff at the online journal Literary Mama, which has also published her poetry. Other work has appeared in The Mom Egg Review, Off the Coast, Tule Review, Crannóg and elsewhere.