Review by Ivy Rutledge

Review by Ivy Rutledge

– In The Beginning Things, Bunny Goodjohn* pulled me right into the world of Willowswitch Lane, where twelve-year-old Tot Thompson has been displaced from her home and into the bedroom of Gareth Strand. There, on his sailboat-printed sheets, Gareth “fed her lines and she ate them like candy,” and Tot dreams that their secret moments are solid love (57). Goodjohn knits into this narrative the stories of Elaine, a woman abandoned by her husband and left to raise Tot and her fifteen-year-old sister Dorothy, and Dan, Elaine’s father-in-law, who has just lost his wife. Dan brings his own desperation and secrets with him when he takes up residence in their dining room on Valentine’s Day.

Tot sees her home as “too full of her sister—full to bursting with reluctant parenthood and bad mood—and of her mother—angry and worried, her mouth perpetually full of dress making pins … all of which made Tot feel as if she were living in a theatre that had no audience, no opening night” (56). Instead, she escapes to the neighborhood park, where she feels a sense of consistency and where she meets Gareth for the first time. Goodjohn counters this unsteady, uneasy relationship with Gareth with the straightforward attention of Keesal, who offers a lighter, easier friendship. It is the see-sawing between the two that launches Tot’s quest for the Beginning Things, those relationship things that happen slowly and honestly.

With each chapter, Goodjohn peels off layers of secrecy and alienation and reveals the family’s bald truths. In her essay, “Place in Fiction,” Eudora Welty said, “Location is the ground-conductor of all the currents of emotion and belief and moral conviction that charge out from the story in its course. These charges need the warm hard earth underfoot, the light and lift of air, the stir and play of mood, the softening bath of atmosphere that give the likeness-to-life that life needs” (67). Goodjohn provides this ground-conductor, exploring the ways that pain and heartache connect us to the places we live. We see the broken fairy tale in the opening of chapter twelve, as the hedge around the Thompson home takes on the qualities of the family itself: “[Nothing] had come of it. Tonight, the hedge was shapeless, a straggly mass of common-or-garden privet. Like the house beyond, and like those who remained inside the house, the hedge had been left to fend for itself” (93). We’ve all seen this house.

Readers will recognize this derailed, fragmented family: the single mother focused on survival, the confused, needy young girl, the teenage mother, and the lonely alcoholic—these are familiar tropes in our social landscape. Yet, Goodjohn rounds out these familiar stories and roots them in their immediate physical and emotional landscape, pushing her characters into uncomfortable spaces and allowing them to grow. This is particularly true with Dan and Tot, as he recognizes her plight, and she discovers his. It is her Dangrad who she confides in when her fantasy life with Gareth comes crashing down, as she “[has]a sense that there were answers here in this room” (97). In order to help her find the answers, though, Dangrad has to teach Tot how to ask the right questions, knowing all too well the danger of not asking.

In fact, the novel covers precisely this terrain of neglect, of not noticing, of relationships fading away. Goodjohn writes, “He had given up with questions and their answers. He just kept on. He just did what he needed to do. He made the tea, he cleaned the kitchen, he tidied his shed, he had a drink. He had another. And then another. Other people’s questions—Millicent’s, Donald’s, the odd remaining friend’s—they dried up in the dearth of his answers. People didn’t ask questions of him anymore, and he didn’t ask any of them” (130). But the situation Dan, Tot, Dorothy, and Elaine have found themselves in requires them to poke into each other’s personal spaces, gently at times and not-so-gently at others, looking for the Beginning Things.

For Tot, the Beginning Things help her understand her own value and the importance of building relationships from the ground up. We all see families fall apart and attempt to rebuild, and readers will find this familiar theme rendered with heart and humor. Goodjohn’s novel weaves together the heartache of things happening in the wrong places and at the wrong time, and she shares with us the story of one family trying to put everything into its right place and succeeding in their own way.

Welty, Eudora. “Place in Fiction.” The South Atlantic Quarterly 55 (1956): 57-72. Print.

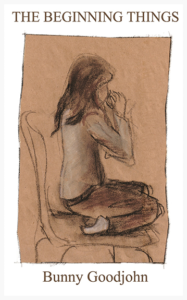

The Beginning Things

by Bunny Goodjohn

Underground Voices Press, 2015

245 pages

Originally from Rhode Island, Ivy Rutledge lives and writes in the Piedmont of North Carolina. Her work has appeared in The Sun, Home Education, Mom Egg Review, Ruminate, and Snapdragon: A Journal of Art and Healing. You can read more at ivyrutledge.com.

*Note: The Beginning Things author Bunny Goodjohn is also an Associate Editor for Book Reviews for Mom Egg Review.