Review by Jill Kelly Koren

Review by Jill Kelly Koren

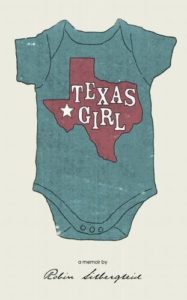

– As a poet who left Indiana to teach in Texas, I entered Robin Silbergleid’s Texas Girl (Demeter Press, 231 pages) expecting to find my own story, but to my surprise I found what Harold Bloom says is the ultimate reason to read: to experience the other. In this unusual memoir, place becomes a character, and a small town in Texas cuts in on the poet’s dance with an Indiana college-town and a quondam lover.

The book opens with an unusual conception: “My daughter was conceived over the phone with my on-again, off-again something-or-other.” Though it may sound odd, Silbergleid lays bare what most women who have dreamed of motherhood do— conceive a child of the mind before taking any physical measures. She does more than dream of her child-to-be, she imagines long scenarios in which they have extended conversations while eating french toast sticks.

In the wake of her grandmother’s death, the idea-child becomes, by the author’s own admission, an obsession. The cycles of birth and death are tightly bound in this story, and Silbergleid’s poet-sensibility finds fertile imagery to illuminate the interlocking links:

Weeks ago, at the hospice center, the nurse had said that death is a process like birth is a process. I turned the analogy around in my mind, until my grandmother became the infant who took her last breath as all of us became the mother’s body struggling…I held my mother by one arm and my sister held her by the other, and as we started walking back toward the black limo, she folded into herself, a tight fist of pure sound. Blood pooled between my thighs. At last my grandmother was delivered.

The links between the mothers in this story are tight; Silbergleid’s own mother was a single mother, and the death of her mother (Silbergleid’s grandmother) makes strong fuel for the The Baby Plan, the idea of which may have been conceived with the something-or-other, but which Silbergleid eventually claims as her own, a maternal lineage. She knows that the only name her daughter can have is Hannah, her grandmother’s name. Despite the playful self-deprecation (at one point she says she hides fertility books under her bed like a teenager’s stash of porn), she is serious about this.

Though the quondam lover, dubbed Dr. Boy, may seem like the obvious choice for the father of this dream-baby, especially since he is the one who set the poet in motion toward Texas, he fades in importance. In fact, everything does. Soon we see the author driving to the big city, thinking only of the baby, the hormone levels needed to achieve said baby, and in what month she might actually become a mother. She says she gives up all her friends, who don’t understand her obsession. She will do this on her own. With the help of a few good sperm donors, a small army of doctors, and an angelic nurse, of course.

While it might seem difficult to relate to this drive (both literal and figurative) to conceive alone, the pull of the quest draws the reader in, past skepticism, past difference. After rivers of blood flow, time and again, the reader is rooting for a keeper, too. And even though I knew from the dedication (“for my children”) that a birth would happen, the tension of the narrative was gripping.

The strength of this memoir is not in its knack for metaphor, which is a delight, nor in its playful-yet-dark taste for irony, which keeps the story from dipping into melodrama. The best thread of this story is its ability to plumb the depths of desire, and not in the traditional boy-meets-girl sense. The desire in Texas Girl goes deeper, to the root of life itself, where the spark of light meets the tip of the darkness that is death. This memoir is not afraid to tell what happens along the way— bumps where needles pierced, clots where implantations failed, trysts that did not end in happily ever after. Old friendships die and new friends bloom to take their place— and in this brave memoir, Silbergleid risks everything to trace that desire and follow it to the end of identity, that place where self meets self. She does not turn away, either from the difficulty of the doing or the challenge of the telling. Through such courage, she dreams both her daughter and her mother-self right into being:

The nurse finally brought the baby to me in the morning…I held her against me, in her pink and blue striped cap, with yellow mittens on her hands, and she curled into a ball the exact size and shape of my abdomen before her birth. I kept reading the information on the pink card taped to the plastic hospital bassinet. 6 lb 12 oz, 19.5 inches. February 10, 2004, 9:32 p. m. Somehow the words made her real.

I expected to be reading this in the comfort of my Indiana home, deep in a reverie of Texas. Instead, I ended up reading it on the way to San Antonio, without my children, en route to a former student’s graduation. Though I started out doubting the wisdom of The Baby Plan (young single mom by choice), my expectations were thwarted, as they often are. There are many paths to motherhood. This Texas Girl retraces hers with humor, grace, and an unflinching bent toward making it real.

Texas Girl

by Robin Silbergleid

Demeter Press

231 pages

Jill Kelly Koren is the author of a chapbook of poems called While the Water Rises Around Us. She began her teaching career in Houston, Texas, and now teaches in Madison, Indiana, where she lives with her husband and their two children. Her first full-length collection of poems, The Work of the Body, is forthcoming from Dos Madres Press of Cincinnati, Ohio.