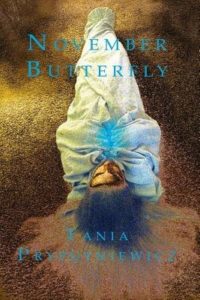

“Pryputniewicz does not flinch from the challenges of the labyrinth—pathways that might lead equally, or randomly, to betrayal or desire.”—Bhanu Kapil, The Vertical Interrogration of Strangers

Author Tania Pryputniewicz on November Butterfly

Author Tania Pryputniewicz on November Butterfly

– Writing the poems of November Butterfly gave me the opportunity to celebrate both the power and the fragility of the female experience as a writer, mother, and survivor of rape during adolescence. Motherhood brought buried layers of shame and fear to the surface from that trauma, initiating my impulse to find ways to protect my children and beyond that, to find ways for us all to survive and thrive.

To withstand the reality of having brought children into a world where trespasses of all kinds routinely occur, I decided to inhabit the personas of iconic women including Marilyn, Sylvia, Amelia, Lady Diana and Joan of Arc among others to weigh in on the spectrum of female agency. During rewrites for section two of the book, Camelot’s Guinevere took over and spoke to me in ways that helped me move past my former thresholds of fear.

The lens through which I’d grown accustomed to seeing things–shadowed by pain and pinned to the past–gradually shifted through the act of writing. My children also brought me constantly into present time with their ceaseless motion. The poem I chose to share below opens with the collision of two realities: the internal past shadowing the perception of the pieces of a broken angel statue and the external present dynamic of my son and his soccer ball. The angel’s conch, held to her ear as an ashtray, doubles as a metaphor for the raw exposure of female genitalia, what it feels like to be a survivor, as if one’s insides are outside and on display for everyone to see.

I finished the poem and sent it to my editor, Ruth Thompson of Saddle Road Press, who encouraged me to let go, stop there, to call the book done. Not long after, on Mother’s Day, as if in psychic attunement to my attempts to reassemble in wholeness, my husband weeded our tiny backyard and stacked the statue’s pieces together. He placed the angel and conch atop torso and feet above wide shell base, filled it with water and served us (and our three children) an omelette on the patio table to the sound of trickling water. I had no idea the statue was actually a fountain, just as I had no idea Guinevere would say, “You can’t write your way home.”

And so, I follow her across the threshold and back into the risks and the rewards of raising my children. And writing daily, yes—but tempered by active engagement with the world I withdrew from in subtle ways for so long.

Guinevere Braves High Noon in My Backyard

A soccer ball kicked by my son beheads statue

of angel that hides our spare key. In her lap, an ashtray

conch. Ear to ground, head next to feet, just as in rapecounselor’s office I drew an x at far side of page

to mark my distance away from rapist. With

noticeable delight–at being right—she repositionedmy x beside x signifying event, pinning me once again.

Just as I pinch Guinevere by thorax, assigning meaning

to sheen and scale as if she’d agreed to float on her ownto back of my palm. Inside trunk of the tree

of her time, barefoot, soaked in moss, striated

by centipede, yellow lichen frills my throatwhile poet revises, circling but mute

as a girl made of cement, headless,

holding the conch of most private self in lapfor anyone to see. What do you think of me now? I ask.

She—I mean Guinevere—neither sanguine

nor sisterly, blurts, with evidentsatisfaction, You can’t write your way

home—as in Let go, take ball back to son,follow him outside fence.

For more info about the author, please visit www.taniapryputniewicz.com.