Review by Mindy Kronenberg

Review by Mindy Kronenberg

It may not be a coincidence that I have received Tsaurah Litzky’s poetry chapbook Jerry in the Bardo for review around the same time as Roz Chast’s graphic memoir of her aging parents, Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, or that it arrived in my hands during the month of both my mother’s Yarzheit (anniversary of the death of a loved one, according to the Hebrew calendar) and my father’s 86th birthday. There is a particular poignancy at this time of year and, for those of us of a certain age, reflecting upon the experience of growing older with our parents. The “Jerry” in the title is Litzky’s father, recalled and presented by his daughter as the man who outlives his soul mate, relishes his daughter’s cooking, struggles and strives against the indignities of old age, and both confounds and celebrates her with unconditional love. The “Bardo,” it is explained in an editor’s note, is a Tibetan word that represents the state of the soul between its death and rebirth.

Litzky’s homage to her father in these 22 poems runs an emotional spectrum of humor and humility. In “Chicken Livers” the vegetarian daughter battles with her own wits as she prepares a dish she knows her father craves (“When I tell him on the phone I’m coming to visit,/from three hundred miles away I hear him lick his lips.”). These are a greater challenge than the meatloaf that used to be his favorite, and though her father is delighted with the outcome (“Delicious, he says, just like your mother’s.”), her imagination runs wild:

When I open the plastic tub, I can’t stop looking;

they look like little labia, oily, frilly, darkly mysterious.

…

While the livers fry, the colors change—

brown fades to purple, maroon, red, ruby, pink, yellow, beige,

like the real stuff of sex—a steamy, many-colored mess.

Her father’s spirit, struggling against the ills of time and memories of a former prowess, emerges in brief and sometimes unexpected ways. In “My Father” we are introduced to the “openhearted” man who wants to engage strangers in conversation, and, despite diabetes and the challenges of gravity, could still possess a dose of vanity:

When he goes out, he wears a baseball cap

to cover the bald spot on his head,

he flourishes his cane before him

like a conductor at a symphony;

it never touches the ground.

He should use a walker; he is too proud.

In “The Persistence of Desire,” post-stroke and moving with difficulty from his wheelchair to his bed, Litzky’s father watches “Desperate Housewives” star Teri Hatcher on television and summons the urge to say “I’d like to jump her bones.”

Litzky’s playwriting acumen is evident in the occasional brief dialogue and elongated statements that rise from some poems with the grace and reflective rhythms of monologue.

In “Here She Is,” a phone conversation becomes a portal to dementia: “I call my father Sunday night at the/ assisted living home in Millersville, Maryland,// Well, he says when he picks up the phone,/ she’s been waiting for your call all day.// Who has been waiting for my call? I want to know// Your sister, he tells me, she is right here/ lying next to me.” The daughter, for that moment, is her father’s sister-in-law, and his wife, gone ten years, is now waiting to speak with her. The episode is as short-lived as the phone call: “So, he says, don’t you want to speak to her?/ Sure is all I can manage,/ Then okay, he says, here she is/ and hangs up the phone.”

In “She Likes Me” the father daughter/exchange focuses on a widow’s attention, marvelously juxtaposed with her father eating from a container of lox spread “like an animal.” His certainty prevails over her cynicism:

Who likes you? I ask

he swallows, The one upstairs, on the second floor,

the one over there,

he gestures over his shoulder with the spoon.

How do you know? I ask.

He speaks even though he is chewing with his mouth full,

I know, he says, she always gives me the big hello.

That doesn’t prove anything, I say,

maybe she’s just a very friendly person.

He snaps back, At eighty-nine years old,

you know a few things.

One of the toughest poems (I imagine to write, as well as read) in the book is the “Great Nowhere,” nearly epic in its complex scenario of her father’s imminent demise, their long distance conversation, her own health issues beckoning her to a doctor’s appointment, and the unraveling images of the past. It is a dramatic and deeply felt distillation of their relationship, the coming to terms with a life passing and one still striving. Throughout Jerry in the Bardo we see the poet’s father as soldier, memoirist, bet maker, lover, husband, and persistent acolyte. It’s a legacy that the poet-daughter crafts with good humor, a grateful sense of love, a gradual and wistful sense of loss, and that eloquently expresses the struggle to keep one’s parents as spirit guides on the continued journey to an uncertain future.

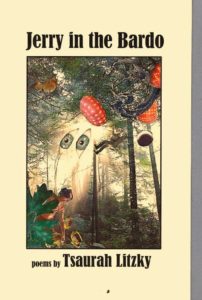

Jerry in the Bardo

A poetry chapbook by Tsaurah Litzky

Nightballet Press

2014

26 pages

Mindy Kronenberg is an award winning poet and writer with over 400 publication credits world-wide. She teaches writing, literature, and arts subjects at SUNY Empire State College, edits Book/Mark Quarterly Review, is a staff reviewer at Weave Magazine, and is the author of Dismantling the Playground (Birnham Wood) and Images of America: Miller Place (Arcadia).