Review by Libby Maxey

Review by Libby Maxey

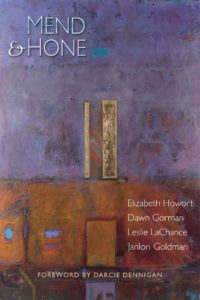

– I love the concept of four chapbooks published in one volume, four poets brought together in a conversation that only the reader can hear. Apparently, this kind of “quartet” is a specialty of Toadlily Press, and Mend and Hone (2013) is the latest in the series. When I began to read it, I expected to find myself listening for the substance of the conversation, but the greatest pleasure turned out to be the sound of the different voices—and they are very different. These poets, all female, do share common concerns, concerns common to most of us: home, ritual, finding a place—in the world, with another person, in history, in a particular moment of one’s own life. Each speaks her own language, however, and the end result is inspiring.

In the first collection, “Turning the Forest Fertile, “Elizabeth Howort draws us back and forth between city and wilderness with playful connections and surprising disjunctions. Howort’s small poems are intimate, but it’s a ranging intimacy with a resonant, fairy-tale quality. Some of the verses capture stress, the lines twisted up in a sort of false tightness, while others gape open with the looseness of silence. The poems flow into one another; no titles to break them apart, and they feel bright, refreshingly thin, never belabored. Her imagery is both simple and deep, clear yet never obvious. When she opens a verse with the lines, “Behind the door is a cradle or a candle. / Both flicker, holding a light that minds the wind,” she leaves us welcome space for thought.

Dawn Gorman’s “This Meeting of Tracks,” my hands-down favorite of the chapbooks, tends toward a more traditional, narrative structure, although her poetry is not formal. She writes with brilliant deliberation and mature artistry; everything hangs together, and without any self-consciously poetic turns of phrase, she paints vivid, haunting pictures full of intense feeling. Her poems are about watching, seeing things, and seeing more than the things seen. This is most beautifully evident in the title poem, in which a woman watches a man with his falcon. Her attention, like the falcon’s predatory stare, is all it takes to bind the two strangers: “he . . . is, at this moment, simply part of her: / there is nothing but their focus, / an invisible thread between them.” Another fine example is “Revelation,” in which a tourist couple’s insipid conversation is forgotten upon the discovery of a ruined abbey. They wander through the ancient space; he looks at her hands;

Finally, they look at each other.

The January light shines

through their eyelashes.

Everything is clear.

Gorman tells much more than Howart, but she leaves the reader plenty of room for contemplation. Her work is warm and full of color—nature is color for her—and there are hints of a saucy sense of humor.

Leslie Lachance gives us more than hints of her saucy sense of humor. In “How She Got That Way,” she often veers into verbal territory too crude for my taste; sometimes, though, her mannered tartness stops just short of that line. “Strange Little Enthusiasms” is a charming game of love and grammar, and her dust bowl drawl in “Everybody Talks About It” (“it” being the rain that won’t come) is perfection. Sometimes, her work seems like nothing but absurdist sass and empty provocation with a wild, poetry-slam edge. But her jerky, scattered lines set her apart from the voices that preceded hers, and her occasional moments of slow tenderness are heartbreaking by contrast to the noise that surrounds them. “Nocturne” is a truly touching thing, as a pair of glasses illustrate a woman’s loneliness, her affair with a married man, and her new loneliness on the other side of it.

Janlori Goldman’s chapbook, “Akhmatova’s Egg,” concludes the set. Goldman is very much a story-teller; she leaves me thinking about the characters in her poems, wanting to know them better, even if they only existed for two and a half lines. Her collection makes a fine pair of bookends with Howort’s, turning as they do on the themes of rustic and urban existence. There’s a mystical and mysterious quality in Goldman’s work, whether she’s writing about 9/11, baking while pregnant, a wounded bear curling up in a station wagon, or the way one old person looks at death. I kept rereading her poems, looking for new ways to think about them—which is typical of my reading throughout this volume, and a fairly high recommendation in itself.

Mend and Hone

by Elizabeth Howort, Dawn Gorman, Leslie Lachance, Janlori Goldman

Toadlily Press 2013

Libby Maxey has a Masters degree in Medieval Studies from Cornell University and has worked as an archival assistant, an elementary school paraprofessional, a voice teacher, a classical singer and a freelance editor. She is on the editorial board of the online journal Literary Mama, which has also published her poetry. She is a founding member of the acquisitions editorial board of Thornapple Books, a small press imprint for literary fiction.