Review by Kathrine Yets

Review by Kathrine Yets

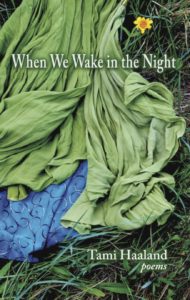

– Everything comes down to the center of Tami Haaland’s collection When We Wake in the Night—the heart. No matter how hard I try, I am funneled there. The collection is divided into five sections—As Many Stories as Stars, Morning and Evening in Your Cup, Inquest, Late Constellation, and Silvery World. Each swirl with emotion into the middle like a nautilus shell.

Let’s start light. The first section, As Many Stories as Stars, is filled with stories, from grandmother’s house to Cinderella on the steps. For the most part, these stories are lighthearted but each has a twinge of unmet desire, leaving the reader unsettled but able to dream on beyond the poem. The turn in “Budapest 1978” leaves this impression:

The one across the table

glances again. His girlfriend

doesn’t like him smiling

at me. The students

want to give us mementos—

lapel pins they drop

in our hands—and he

chooses me. He gestures:

could he? My dress?

He slips his fingers under

the neckline, and the pin

moves in, his fingers

protecting my skin.

We look but don’t

linger, and what words

could we speak? I remember

the place, the singing.

I still have the pin.

For a moment, it feels this poem is about to get hot and heavy with this student’s “fingers under/ the neckline,” and the reader moves from line to line with anticipation and high hopes for this encounter. Desire is denied, though. This is reality, and the check it clear: “We look but don’t/ linger, and what words/ could we speak?” But still, the impact this encounter left, the sexual suggestions, are prevalent in the final lines, allowing the speaker and reader to dream on.

Looking at this collection as the sections spiraling to the middle, we rotate to the last section. The final section, Silvery World, is light hearted like the first. Each poem travels to different places, crosses worlds. Life is shown from many angles—the artist, the salamander, the blue jay, the girl in a monkey cage. These are not persona poems, but written in Haaland’s perspective, so we get an outsider’s view in. I feel the first stanza of “She Eats an Apple as the Salamander Observes” gives a good glimpse of what I am trying to convey:

It swims in a stainless steel bowl

where I might wash spinach on another day.

A flat rock placed strategically makes it feel

safe, the way people in the Titanic felt safe

when they experienced the merest shudder

and went on dancing or climbing into bed.

Here is the “silvery world” of the salamander, the bowl it calls home. The reader is observing life outside of themselves along with Haaland.

In the second section, Morning and Evening in Your Cup, many of the poems are about Halaand’s children, reminiscing on the past. A personal favorite “Swim Lesson” looks into a past fight between a son and mother (Haaland), “Arguing over whether he will go—/ he will go—whether he will go again,” and a mother’s realization her son is growing up a bit, “At the pool, his thin/ new body slips into a world/ that does not include you,/ and you watch, holding his coat.” The son is beginning to have independence but mother still watches close by (he is only 11, after all). Between these happy memories, harbinger poems creep in, suggesting the darkness that is to come. A taste of grey can be found in “Stilled in Flight,” “Am I wrong to think we can divide time/ and time again to get more of it?… I understand you will leave soon/ and your decision, like every/ passing minute, has its own mind.”

Rotating to the second to last section, Late Constellations, more melancholy poems can be found. When I first read the section title, I read it as Late Consolations, and I wonder if this (mis)connection is meant to be. There are many poems were it seems the speaker feels comfort was given to the addressee of the poem too late. For example, the final stanza in “Can’t Help,” “Swim harder. Think first. I wish you could fly./ Pause here. Say more. Put the gun down.”

It all comes down to the heart of the collection, Inquest, spiraling into despair with little warning. Haaland gives us the cold hard fact: a young man committed suicide. The poems in this section moved me; I found myself crying, shuddering. To write a truth like this takes more than courage—it takes a mother’s heart. In a few of the poems, Haaland writes in the perspective of the victim’s mother, “He’d sit at the kitchen table, feet dangling,/ copy in his penmanship book… He made us feel like he was// the best boy. Lucky then, but what could/ we have done, and when? To have it back” (“1. Penmanship”). Haaland takes what details she knows from the case (“They say in those last minutes/ he wrote the alphabet, capital first, then lower case.”) and uses her poetic license to fill in the story of the boy’s life. Through a mother’s eyes, the reader sees her anguish, feels her pain from such a loss. Haaland captures this heartache as a mother herself, especially in “11. In Secret I Make My Plea,”

I look at his picture.

Don’t die, I say. The face

looks back. Don’t.

The speaker in this poem could be the mother or Haaland herself. Either way, this short poem is chilling. All the poems in this section made the collection with their authentic depth.

When We Wake in the Night by Tami Haaland

WordTech Communications, paper 96 pp.

Kathrine Yets is a graduate of the University of Whitewater–Wisconsin, majoring in English with a writing emphasis. She spends her days reading, writing, and playing with flowers as a florist at Sendik’s.