Review by Tara Betts and Marjorie Tesser

Review by Tara Betts and Marjorie Tesser

– Note: In Looking Up Harryette Mullen, Barbara Henning interviews Harryette Mullen by means of a correspondence. Poet Lee Ann Brown suggested that poet and educator Tara Betts and MER Editor Marjorie Tesser also correspond in reaction to the book.

Dear Tara,

When poet Lee Ann Brown suggested we collaborate on an epistolary review of Looking Up Harryette Mullen, I was excited about the idea. You are a poet and teacher, and I’m a poet and editor, but not an academic; I thought we’d possibly have different takes on the material.

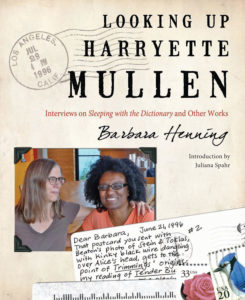

Looking Up Harryette Mullen tracks an exchange of letters between the interviewer Barbara Henning, herself a teacher and poet, and Harryette Mullen, the author of the National Book Award finalist Sleeping With The Dictionary and other acclaimed works.

In the course of their correspondence, the mechanics of the poems’ construction –or birth–are revealed: the formal constraints (Mullen utilizes OULIPO and other techniques), the resulting architecture, how the rules were employed in a particular poem.

Although Mullen’s initial approach to a poem can be intellectual, the resulting piece is often deeply personal and emotionally compelling, as formally chosen words give rise to associations personal and political, resonant and humorous. Mullen is literally in conversation with the dictionary, as words are chosen for their nuanced layers–cadence or alliteration, implications as well as official meanings. The rules of the form can ultimately be bent or even scuttled in service to the poet’s intent.

The book kind of reminded me of those articles in Guitar Player Magazine or Modern Drummer, where the musician details the particular instruments, pedals, gadgets, and techniques used to achieve a dazzling solo or effect.

Reading about Mullen’s technical approaches inspired me, not usually a formalist, to utilize some in my own practice. And the descriptions of particular poems, as to what the poet intended, and the reasons for specific word choices, were fun and interesting. Ultimately, the book’s great success is in its faithful rendition of creative process, the diverse streams that culminate in a work of art.

As a teacher, do you have a preference for certain types of poems? Is this a book you might use in class to analyze Mullen’s poems or suggest poetry methods to your students? As someone familiar with Mullen’s poems, did the explanation of any poem surprise you, or even contradict what you had thought about the poem?

Look forward to hearing from you!

Best, Marjorie

Dear Marjorie,

My introduction to Mullen was through her book of quatrains Muse & Drudge around 2000. After that, I sought out her other titles. I have most of them except Tree Tall Woman and Blues Baby. The interaction between Barbara Henning and Mullen as a concept engaged me deeply in Looking Up Harryette Mullen. Besides Mullen’s work, the collaborative efforts between two women in an intellectual exchange and conversation about the craft and process of writing is something that I do not see often enough, even with publishers and journals like Calyx, Delirious Hem, Switchback Books, belladonna, Bone Bouquet, TORCH, Meridians, and many others. The textures and visual aspects of their correspondence spoke to me as a reader, and a writer, because I wanted to see and imagine the feel of the postcards the Henning and Mullen shared. What was their handwriting like and what surrounds their writing? Seeing those artifacts that documented their communication gave me an insight to how other happenings impact and sometimes distract us from writing. The letters also took a turn toward the personal, while elaborating on being in the classroom, texts, and artists like Tyree Guyton and Simon Rodia. The myriad influences that writers accumulate, are subtly revealed in new texts, or take new directions, evident in those letters and postcards and the micro-analyses and comparisons of poems and excerpts shared by Henning and Mullen.

In the second half of the book, Henning and her students address Mullen in a Q&A format that not only spoke to Mullen’s process, but focused more specifically on her development toward Sleeping with the Dictionary, her first book on a university press. I would have liked to hear more about the earlier books, but again, Mullen’s playfulness, list-making, and describing her growing awareness of her process and influences, makes this book helpful for people who are reading Sleeping. The earlier books are mentioned enough to make one curious to find them or hunt down Recyclopedia, which collects much, but not all of Mullen’s work in one volume.

As a teacher, reader, and reviewer, I do think I lean towards certain types of poems. Although I think my taste in poetry is growing broader all the time, Mullen has been a poet that I revisit, among others. I like narrative poems, word play, formal poems, and the lyric. Sometimes, experimental poems blur the lines between those forms, such as the evocative poem “We Are Not Responsible” in Sleeping With the Dictionary. That poem has become even more relevant when we consider racial profiling and the screening at airports now. The poem assumes similar language to Miranda Rights and scripts that we have heard on loud speakers before catching flights. Mullen’s inventive turns in language can and do gravitate around a subject and make narratives in an unexpected way.

Since the poems discussed are surprising and the interviews are informative about the process of creating said poems, Looking Up Harryette Mullen would be a natural companion to teaching a class that considers Mullen’s work, contemporary poets, women in conversation about the craft of writing, or how OULIPO has impacted poets now. I do think that it would be helpful to share the poems that Henning and Mullen discuss. Although Juliana Spahr’s introduction is brief, it offers thoughtful insights about Mullen’s earlier work and its connections to OULIPO, and I appreciated that Spahr notes that a particular member of the OULIPO community was discouraging of not only women being admitted to this predominantly male movement, but that there were no plans to admit a black lesbian anytime soon, according to one Oulipian. So, it follows that there is still a need for these spaces where women do more than affirm each other’s work, but create literature and write about what women create with intelligence.

When I think about how Mullen returns again and again to the dictionary, thesaurus, and an etymological dictionary, it is as if she is trying to get to the root of each word while conflating our associations with those words. There is a power in language that dismantles forces that would seek to limit the use and possibilities of language, and that makes this slim volume even more engaging. I’m curious what was in these letters and questions that made you consider your process, but perhaps, it is better to leave it as an open book with entries that we both could explore.

Best,

Tara

Looking Up Harryette Mullen: Interviews on Sleeping with the Dictionary and Other Works

Barbara Henning

Belladonna 2011

Tara Betts is an author, a Ph.D. candidate at Binghamton University, and a Cave Canem fellow. Tara’s poetry and prose has appeared in various journals and anthologies. She has also contributed to interdisciplinary collaborations such as John Sims’ “Recoloration Proclamation” and “Rhythm of Structure” installations, filmmaker Nijla Mu’min, and Peggy Choy Dance Company’s “THE GREATEST: An Afro-Asian Tribute to Muhammad Ali” among others. – See more at: http://tarabetts.net

Marjorie Tesser is editor of Mom Egg Review and a writer.